Zé Povinho, always the same

BY José Augusto-França

Zé Povinho was born on 12 June 1875 (with the inscription “Your Zé Povinho” on one of his trouser legs), donating to the candles for Santo António collection on the eve of the Lisbon patron saint’s feast day, making Lisbon the scene of representation. The periodical he appeared in was A Lanterna Mágica, the issue published on 1 May and valid until 31 July, two or three weeks before Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s sudden departure on a lengthy visit to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. The publication was a contracted continuation of his career as a caricaturist for three successful publications. Rafael Bordalo was already hugely popular and his popularity was to continue to grow when he returned from Brazil, through other periodicals that were the weakly sustenance of literary, artistic, theatrical and political life in Lisbon. Indeed, it was to continue to grow until his death at the age of 54 in January 1904.

A Lanterna Mágica was an “illustrated review of events of the week” edited by Gil Vaz, a collective name used by the poets Guilherme de Azevedo and Guerra Junqueiro, the authors of a scandalous play that was to be banned four years later: “Viagem à roda da Parvónia” [Travels Around Cuckooland], the motherland of two or three, to name just a few, of the generation of the Casino Conferences, which Rafael Bordalo had already commented on at the time (1871) in A Berlinda.

Zé Povinho emerged at an opportune moment in the history of the motherland/Cuckooland, at the close of Romanticism, in the year of publication of O Crime do Padre Amaro by Bordalo’s friend Eça do Queiroz – which nobody other than Rafael Bordalo could have illustrated, if that had been the case… Portugal had also completed one quarter of a century of “Fontism”. In Fontes’s support, Zé Povinho responds to the collection, that he is Santo António Maria Fontes Pereira de Melo, on his popular throne, and the one doing the begging is his Treasury Minister, António de Serpa. Supervising the scene, whip in hand, is the latter’s baron, from the River Zêzere, the feared head of the city council. On the saint’s lap, with a little crown on his head, is the Baby Jesus/King Luís I.

Lithograph

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

A Lanterna Mágica, 26.06.1875, p. 52-53

MRBP.RES.18

Whilst the following cartoon on the feast of St. John (embodied by Andrade Corvo, the Minister of Foreign Affairs) with King Luís as a lamb, does not feature Zé Povinho, he returns for the third popular saints’ feast of St. Peter (S. Pedro… Paio), who is represented by the minister Rodrigues Sampaio in “denying” his past as an anti-Cabralist slinging stones at the clandestine O Espectro of the 1840s, which appears in the drawing as the saint’s cockerel responding a wise “no” to the biblical question. Zé Povinho looks on, on his hunks, commenting that it is “always the same” – referring to either the events of political life or himself throughout the centuries.

He was only to return in the 14th issue, the publication’s success now making it a daily instead of a weekly publication, to comment on the increase in railway ticket prices, and in the next issue, to make an observation on the fervently reformist Bishop of Viseu leaving political life: “Alves the democrat” versus “Dom António the papist”. In both cases, Zé is “always the same”, multiplied in half a dozen images, watching amazed, ingenious, with his behind on the ground. Or sleeping, in the midst of the hustle and bustle of deliverymen from Rua dos Fanqueiros because of the Sunday rest. What can he, Zé, do? When the opposition, which was soon to declare itself “progressive”, given the aforementioned increase in rail prices, asks him if he is going to continue serving the government, his political-philosophical response is “What am I to do?”… And how would he know?

Preparations for 24th July Parade

Lithograph

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Lanterna Mágica, 22.07.1875

MRBP.GRA.164

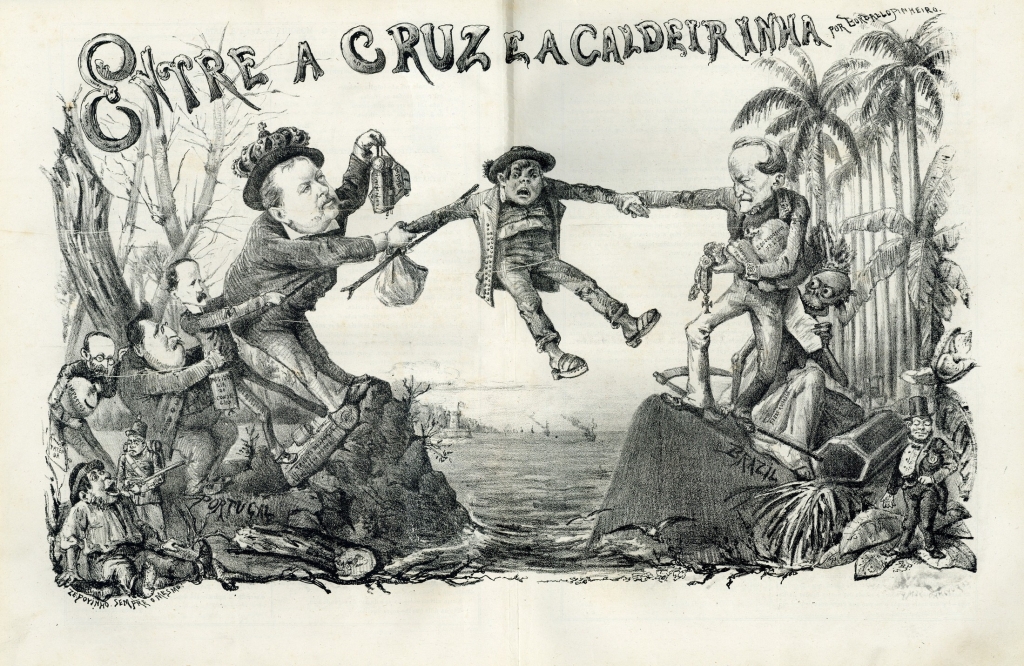

The “one hundred valuable pieces of artillery” in the 24 July parade provoke the usual astonishment in him, without understanding that it would have been better, given the cost, to give him schools. And it is as a school-aged boy that he appears in no. 26, dumped on the floor of Rossio, his finger up his nostril, outside the building where the king and his ministers are playing with lead soldiers. He is “Zé Povinho, junior”, who appeared only once, a figure that seems to traverse the ages, but is not necessarily needed, as we will understand later, for the timeline/biography of the myth. However, the most important figure in the work of Rafael Bordalo, throughout the years, after the Brazilian interlude – where there was no point in Zé Povinho appearing, or as “Manuel Thirty Buttons”, the emigrant “between the devil and the deep blue sea”.

Lithograph

Signed: “RBP”

Published in O Mosquito, 08.04.1876

MRBP.GRA.1147

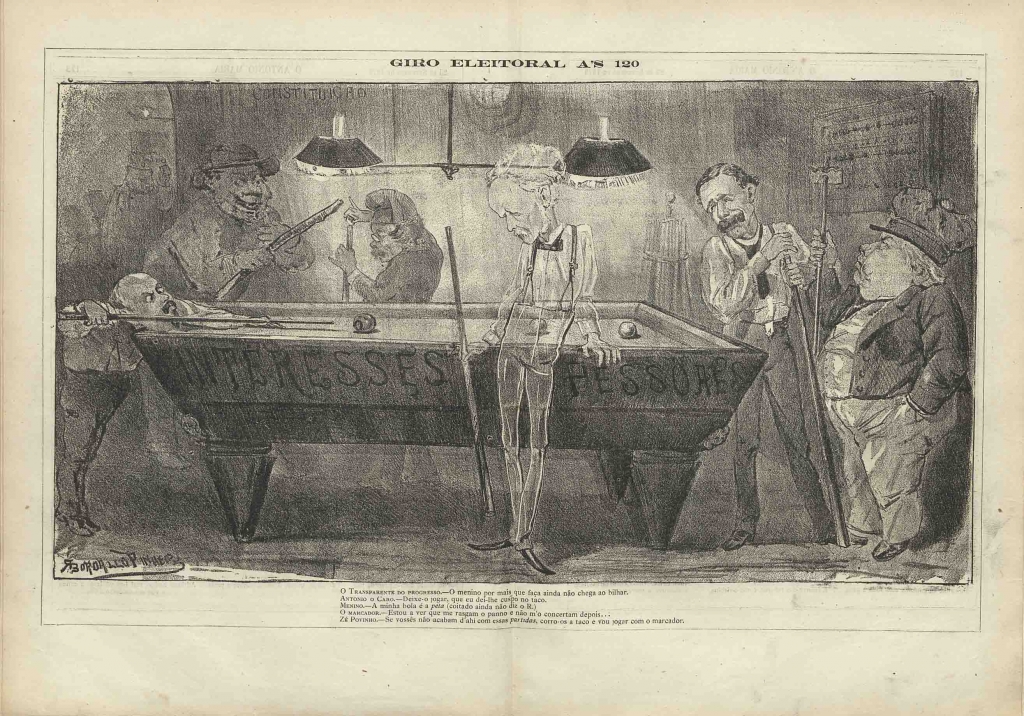

Upon Bordalo’s return to Portugal, or to Lisbon and its Chiado district, Zé was immediately to be found on the front page of the new periodical, O António Maria, launched on 12 June 1879. In government at the time, reflecting the rotation of the two major parties, was the “progressive” party which had defeated António Maria Fontes’s “regeneration” party. Zé’s life was now to take on greater historical (and mythical) significance, carrying the letters of his name on his back at the top of the front page and, inside, sitting on the ground, “always the same”, as we have come to know him, watching the political procession of the day go by, under the surveillance of countless Fontes figures. Within a short time, the new government minister, the already famous Zé Luciano, would distract him with luminaries to get his vote…

O António Maria was to continue to January 1885, its end corresponding to Rafael Bordalo’s indignation at the press’s lack of reaction to censorship measures. For more than six years, with the literary collaboration of Guilherme de Azevedo and Ramalho Ortigão, the periodical reviewed the daily life of the country and the city, as well as the theatrical, literary, operatic and sports life, in critical permanent observation that the verses of Pan-Tarântula were also to comment on later.

Lithograph

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 25.09.1879

MRBP.GRA.1088

All figures from the two parties, and any other useless party that emerged, are featured, above all members of the government, and always Fontes and Braancamp, the alternating chiefs, and the good king Luís, the moderating power who did what he could in this insipid constitutional period… An Album of Glories, with images highlighted in colour, was to be published in parallel, with portraits also penned by Ramalho. It constituted an addition to the social culture of the country in the face of its main protagonists – kings, princes and ministers, politicians and writers, actors and institutions (such as the Constitutional Court itself and Coimbra University… poor things!). And Zé Povinho, who Ramalho Ortigão describes as “the Sovereign”, almost fifty years of age, a child of the Charter and parliamentarism, who “sleeps, prays and cheers where required”. But not just…

Because Ramalho goes on to say that “a day will come perhaps when he will change appearance and perhaps also change name, from Zé Povinho [povinho = little people] to simply People”. This was in September 1882, seven years after the creation of the figure that we have seen evolve, and will continue to do so, in the pages of the publications. Predicting future developments, Ramalho Ortigão goes on to say: “But many new taxes, new loans, new treaties and new discourses will run through the constitutional hourglass of time before that tumultuous day arrives”. The dates we know in the history of Portugal refer to 1891 and the Porto Revolt of 31 January; 5 October 1910, with Rafael Bordalo already dead and Ramalho’s hopes changing. They would continue throughout the 20th century referring to various struggles, for example 7 February 1927, the revolution of 25 April 1974, which almost coincided with the centennial of Zé Povinho, which was to come shortly later, as we will see. Historians may ask themselves if Zé Povinho was present at those events, and with what reason or certainty, and disillusions also.

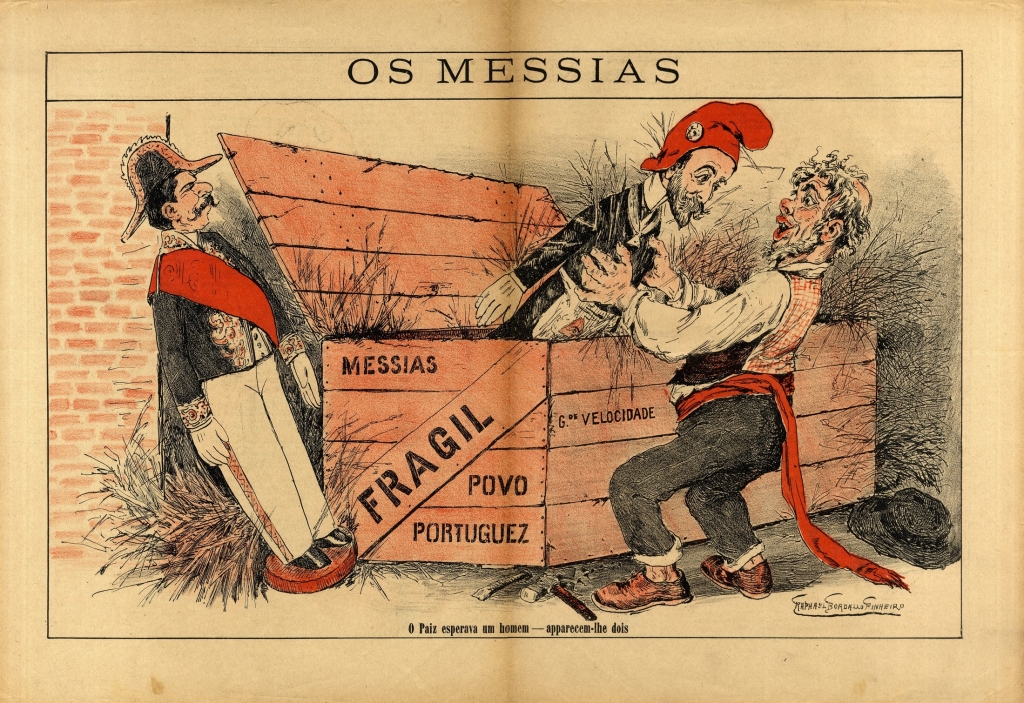

The latter were certainly present in the Bordalo’s drawings in O António Maria before and after the Album of Glories, and in the periodicals that followed – up until November 1904, the last time Rafael Bordalo drew him, now with diminished significance. Before this, however, he had asked Zé to pick between two political solutions laid before the country in 1904, referring to the “Messiahs”, one on the side of King Carlos, who was the future dictator João Franco (whom fortunately, Bordalo was not acquainted with); and the other, an anti-monarchic “progressive” M.P. who was to become a republican, Bernardino Machado. Zé was to choose one or the other, picking one out of the box received at great speed; he chose the republican, to later, as we know, go from revolution to revolution. But Zé Povinho had by now grown old, appearing in the drawing with white hair and beard, which was only the case once (or twice), as if reflecting, in the process of the character’s evolution, the ageing of his creator, who was to die only a few months later.

.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Paródia, 04.02.1904

MRBP.GRA.1038

Almost thirty years lie between the first image we saw and this (almost) final one, over five publications which, the Brazilian interlude excluded, did not stop – one after the other, always the same, perhaps changing name, because of an argument the first time or out of spite against censorship two other times, and for publishing strategy reasons the last time, at the dawn of the new century. Twice the periodicals questioned themselves: O António Maria after A Lanterna and, in between those two, Pontos nos ii. which Bordalo desired, in a situation of professional dignity in 1885, proceeding to put them, as always, but without saying it, in complicity with the renewed mention of António Maria Fontes, who in 1891 had been dead for some years and was now a historical figure, with impunity, when the revolt of 31 January brutally put an end to Pontos no ii . A Paródia was a new lease of life to which, with a certain degree of delusion, the artist, a very popular figure, devoted himself – with a new collaborator, the republican João Chagas. Later came Fialho de Almeida and Eugénio de Castro (who barely warmed his seat), with Bordalo observing, with him gone, no one else could carry his torch, not even his son, Manuel Gustavo. At the age of 50, Rafael Bordalo was still capable of depicting the “Portuguese comedy” in its daily Lisbon practice, which had changed in aspect but not in structure. On 17 January 1900 it was “the dance of the Bica in Prazeres cemetery”, “the corpse pawned, the soul given to merrymaking”: “caricature in the service of the great public grief”. Politics was (or continued to be) “the big sow”, finance was “the big dog”, the economy “the brooding hen”, parliamentary rhetoric “the great parrot”, national progress “the great crab”, bureaucracy “the great rat”, public education “the great donkey and the reactionary fraction “the great [Jesuit] mole”. Manuel Gustavo helped his father in this zoological vision of Portuguese life as much as he could, and in the middle of the political ups and downs of these two soulless parties and their minions, Zé Povinho remained the eternal observer, or “always the same”.

Thirty years of adventures and misadventures thus gave life to Zé Povinho in his presence on the national scene. Examples of this are of two kinds – both active and passive, and much more of the latter on account of his apparent definition as “always the same”, sleepy or dumb, ignorant of the causes but sufferer of the effects.

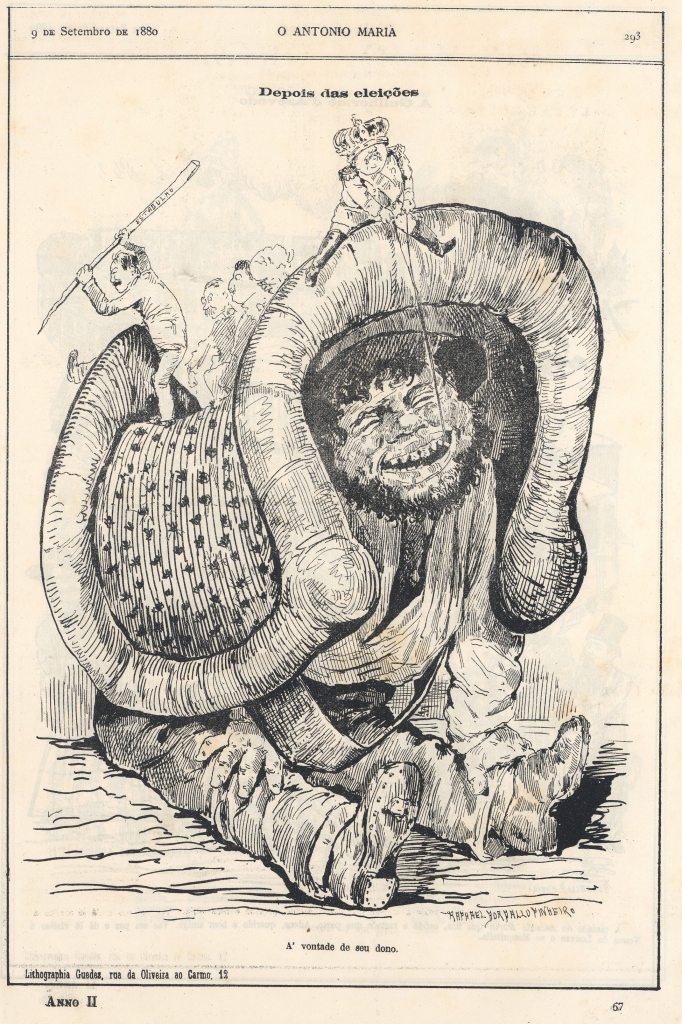

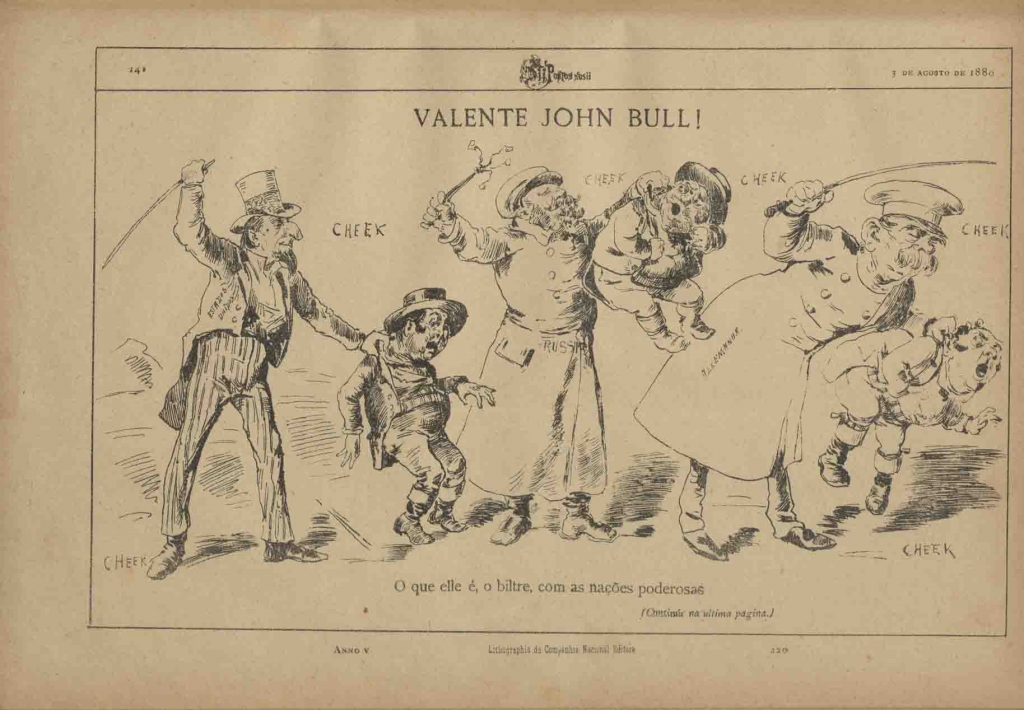

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 09.09.1880

MRBP.GRA.228.1

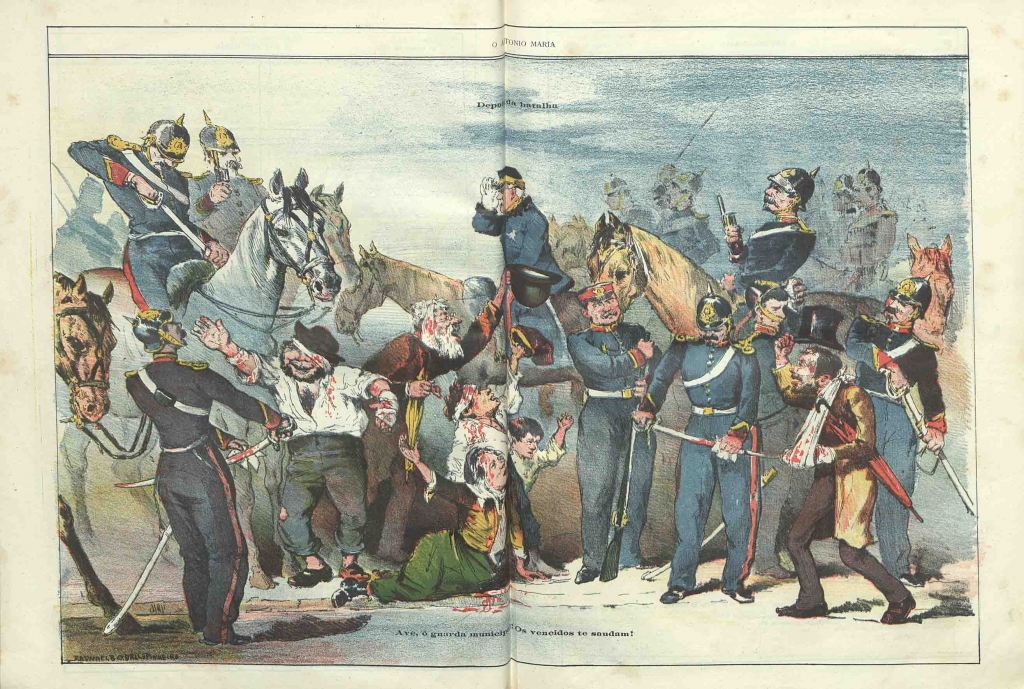

In the first image that determined the symbolic presence of Zé we see him sitting smiling, underneath a huge donkey saddle that Mariano de Carvalho had prescribed him in a newspaper article that was more cynical than usual for the reign of Luís I. Curled up on the edge of the saddle is the king himself who, as if holding a bridle, holds a cord in his hand that is attached to one of Zé’s teeth, whilst behind him the famous politician pokes him with a stick, making room on the saddle for the government members and “progressives” of the day. “Saddle, Royal Sire!”; a recipe that stuck, as it was with the saddle that the poor, smiling and content Zé was always to be seen. Later we would see him as a clown, wearing a carnival mask, between the king and Mariano, who, dressed as a gypsy woman, reads his palm – only for him to be beaten by the Municipal Guards, greeting the victors who clean their sabres, under the command of a tiny general, Macedo.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 17.03.1881

MRBP.GRA.1082

Still later we find him carrying an ear of wheat (marking Ascension Thursday) on his back. Once again the victim of taxes, he is tied to a pillar amidst the centurions of government. He holds a green reed in his hand – but could it become a baton or stick? In any case, Zé is not welcome at the political feet-washing feast of Holy Week; the budget did not include soap for him.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 07.04.1881

MRBP.GRA.1083

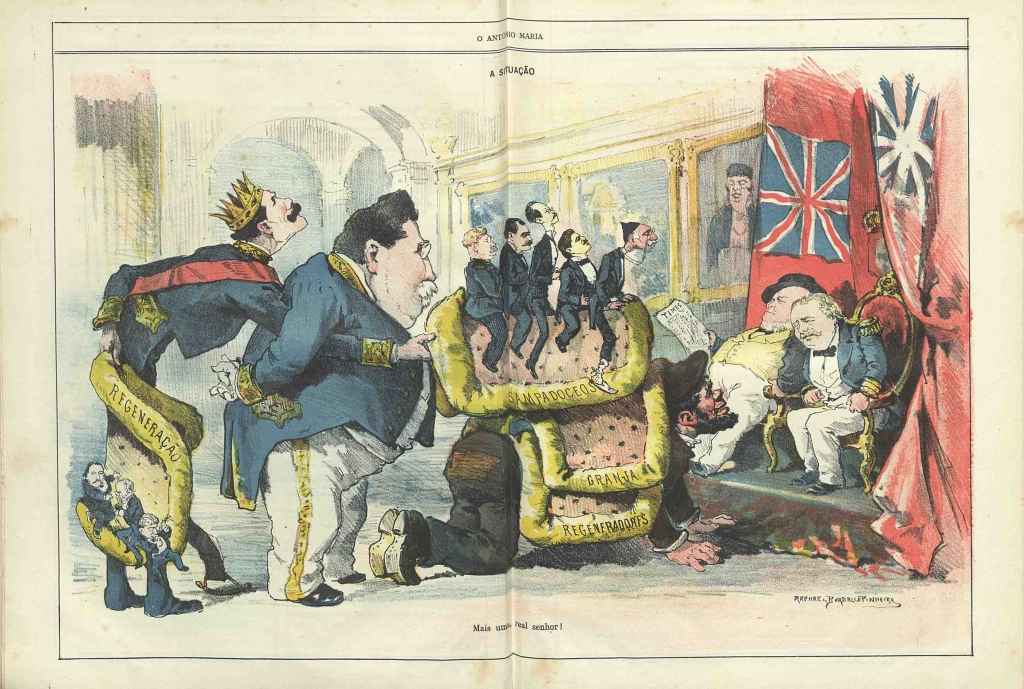

In the same year, 1881, it was not just one but three donkey saddles that have him get down on all fours before the throne the good king shares with John Bull.

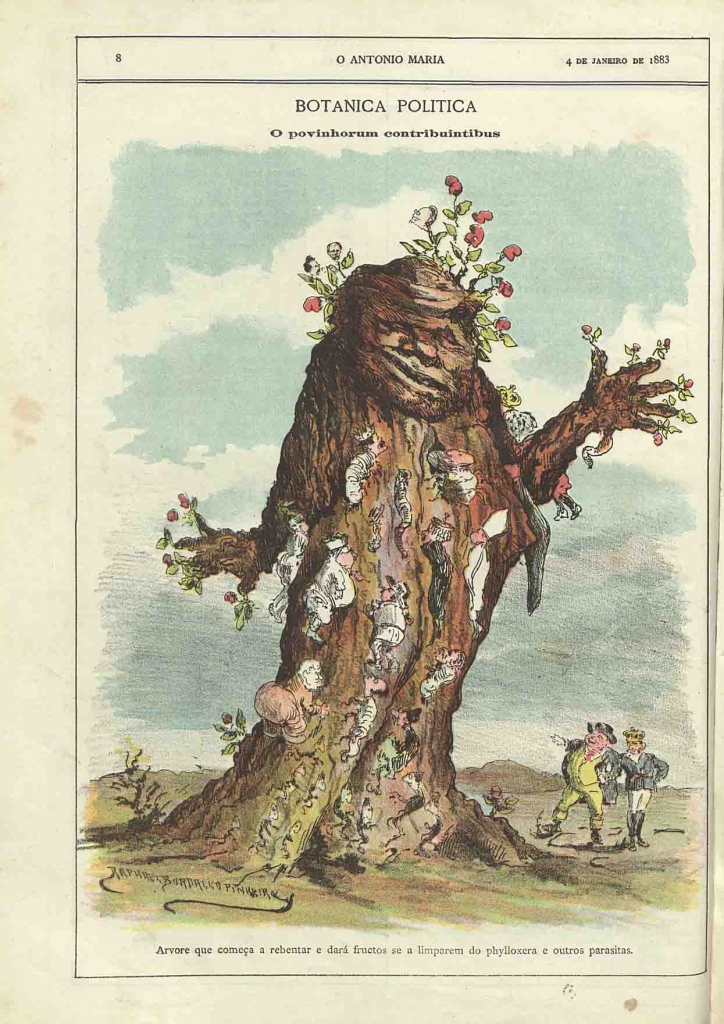

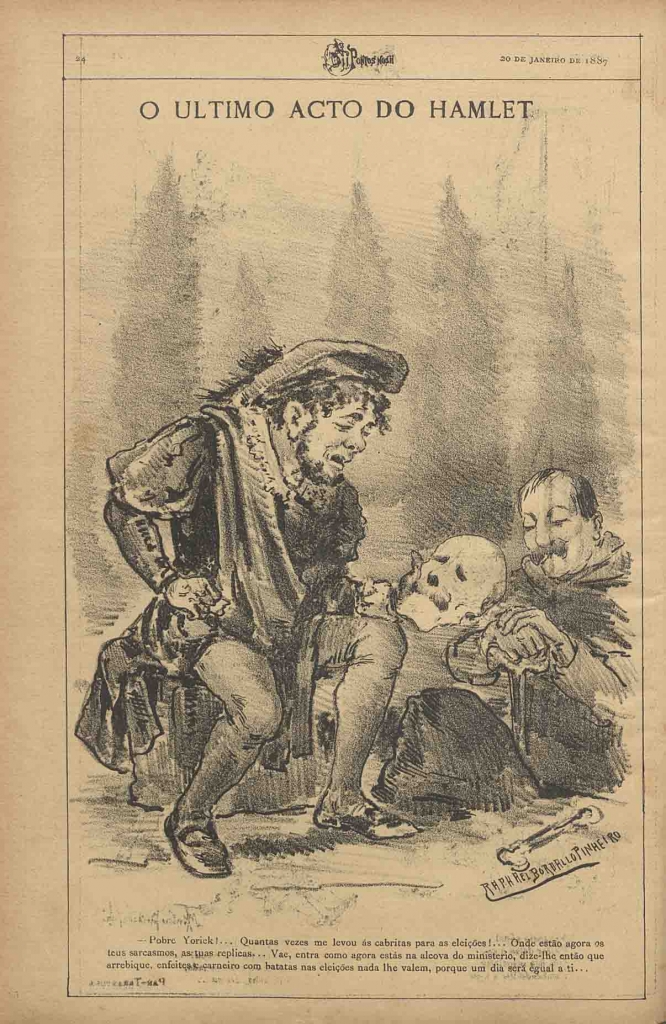

The same situation that the old Sampaio is now sharing with Fontes. One year later, and we have Fontes dominating the image, protecting the interests of Salamanca against the railway unions, with multiple Zés in the circles behind paying admission fees. It was a nice little arrangement between Fontes’s politicians and the famous banker Burnay that left him in Spanish clothing. If only he could, he would kick them out! But fear of the Guards’ “scabbard fish” won’t let him. He does, indeed, have the elections where he is sovereign, and he finds himself pampered on polling day – only to be chased with a stick by the same elected representatives a day later. Poor Zé is made of wax – and he melts in the brilliant sunshine of the eternal Fontes; or he is a rotten tree full of worms, each one with a recognisable face drawn in great detail. If only they would cure him of phylloxera and other parasites! Or of the cunning heitaras that surround him and seduce him – all of them also well-known and clearly recognisable while wearing political carnival masks. It is Fontes who, in 1886/87 (he was soon to die), wearing the mask representing the leader of the opposition, Zé Luciano, asks him if he does not recognise him.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 04.01.1883, p. 8

MRBP.RES. 2.5

Oh no! He is “the same as last year, with a different mask”… But what can Zé do other than to wait for alternatives? And if they give him a wedding feast fit for a prince, he opens his mouth to emit “aaahs” of amazement and gratitude, knowing (or choosing not to know) that one day later he will be shouting “ooohs” of lament, when the taxes rise once more. In any case, he is left to deal on his own with the old and sad “Portuguese agriculture”, “a consumptive propping up a dotard”. Once again, all he can do is scratch himself where the fleas bite, the same fleas that, in 1898, Zé Luciano leads in a dance. Again they are portrayed with recognisable faces, revealing Rafael Bordalo’s peerless talent for achieving mini-portraits the size of a pinhead, or trained fleas, in the Parliament chambers. Where the drunken feasts continue – with Zé paying for them, he cries, with the aureole of a martyr… Or with a crown of thorns on his head, with the return of taxes in 1893, after so much British niceties in wasted international meetings, with John Bull always tightening his grip around his throat wearing the gifted cravat to make things look better.

We already know he had been hanging by the throat since 1881, strung up by the treaty of Lourenço Marques, or 1883, a bell-wearing manikin as described by Victor Hugo in the Court of Miracles, in which they all perform: Fontes still watching his successor Hintze, who is carefully trying to steal, without causing a stir, the quintain. And he will succeed, as others before him have and others after him will… Ah, the greedy face of the next head of the Regeneration party, his able little hands ensuring corporal balance and stability of the victim! Victim, yes – but… The very same Hintze we see again in 1884 or 1883, subtly on the margins of a public banquet, or perhaps even kicked out, one of the rare occasions of violence from Zé Povinho. The excellence of the drawing matching perhaps the excellence of that decision. In the first case the minister was merely marginalised, placed outside the drawing that represents all the national political figures – from the king and prince to the bishops, ministers and more general figures – sitting at a banquet table to mark 1 December 1884, under the branches of a tree where birds representing figures such as Burnay defecate down on them. Zé is serving tables, in the livery of the Royal Household, or dressed as a sacristan or an invalid; or also appearing as the cook, carrying a tasty tray of food to the table without noticing the hungry who surround the banquet scenes – both white (the schools, fisheries – one can read on the figures) and also black, which, at the time, was not a custom in good conscience. Hintze sits alone outside the represented context, from where we had earlier seen him being expelled because of a case of fraudulent use of his power as Treasury Minister in a public tender procedure for the Portuguese customs.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 03.01.1884

MRBP.GRA..2598

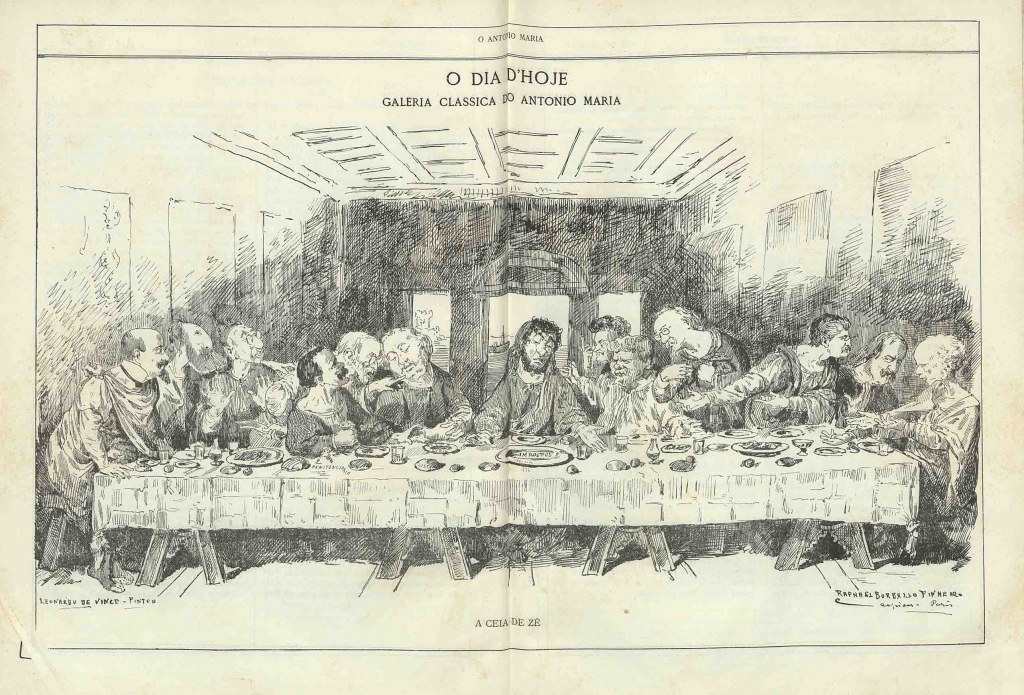

Poor Zé, who in 1886 was forced to strip and pay, with the shirt off his back, the wedding feasts for King Carlos and the ruling classes. And we have seen him naked before, with nothing left to take off, as the Treasury Minister demanded of him in 1881, until he was just skin, or less than that, a mackerel bone; in January 1885 or March of the following year, addressing two successive governments, of Fontes the “regenerator” and Zé Luciano (“dialogue between Zés” is the title) the “progressive – it doesn’t matter which for the condemned body… Condemned as Zé – Prometheus chained to the rocks and devoured by the British vulture. Or as Christ himself, presiding over the Last Supper in the crisis of 1881 or the political routine of April 1882.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro copied Paris”

O António Maria, 06.04.1882, p. 108-109

MRBP.RES. 2.4

Imitating Leonardo’s painting did not go unpunished, as the inspiration was considered sacrilege and the case went to court – even if Rafael Bordalo put himself in the place of Zé Povinho or Christ, surrounded, as he was, by judges and the officers of the persecution he suffered. For Zé Povinho, in this definitive moment in the life of the figure he is compared to, the twelve table companions, as the scriptures have it, range from King Luís to Burnay and include, seated in the appropriate places, the protagonists of the rotating political scene of the day. They are all recognisable: Fontes is Judas, depicted with a gesture befitting his incarnation. In front of Zé, a banner says “Taxes”… Zé Povinho the victim is, in this composition, the maximum representation of his own saga, and there is nothing more he could say, or they would let him say, without court action…

From there on, in a timeline that may be subject to inversions, depending on the given situation, he can only be crucified, and resurrected, as a revengeful god, the People desired by Ramalho in tumultuous times… Zé Povinho can thus be an active and threatening symbol, by giving up complaining and his laziness and fears. This takes place parallel to the other victimisation discourse, and it is important that things are this way, given the fatal ambiguity of the character, his ideological references and the gentle character that was said to agree with the Portuguese. As such, he was born as a response to an institutional fundraising action, within a context of obedience to the powers constituted by the liberal and constitutional monarchy. The servers of that scenario, by means of the sedate actions of the governments that diverged only in formal terms or in terms of their clientele (as, indeed, one Count of Abranhos, and many of his political partners, understood), deserved criticism and scorn – very rarely applause. Except at the hour of death (one cannot ignore what was a point of honour for Rafael Bordalo), as in the paradigmatic case of Fontes in 1887, reflecting his historical eminence that defined the latter half of the century.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Pontos nos ii, 20.01.1887, p. 24

MRBP.RES. 3.3

Zé needed the addition of text in the no. 10 issue of O António Maria, so that he could be identified by the reader, and his name is written on the stick in his hand. “If I have to go there with this stick, may the devil take them all”. By all he means the politicians/puppets (including the king) who, depicted on the shelf of a fair stall, are targets for the balls thrown by government members, i.e. balls supplied by Sampaio and Fontes. This is the drawing known as “Pim Pam Pum”, after the name of the stall.

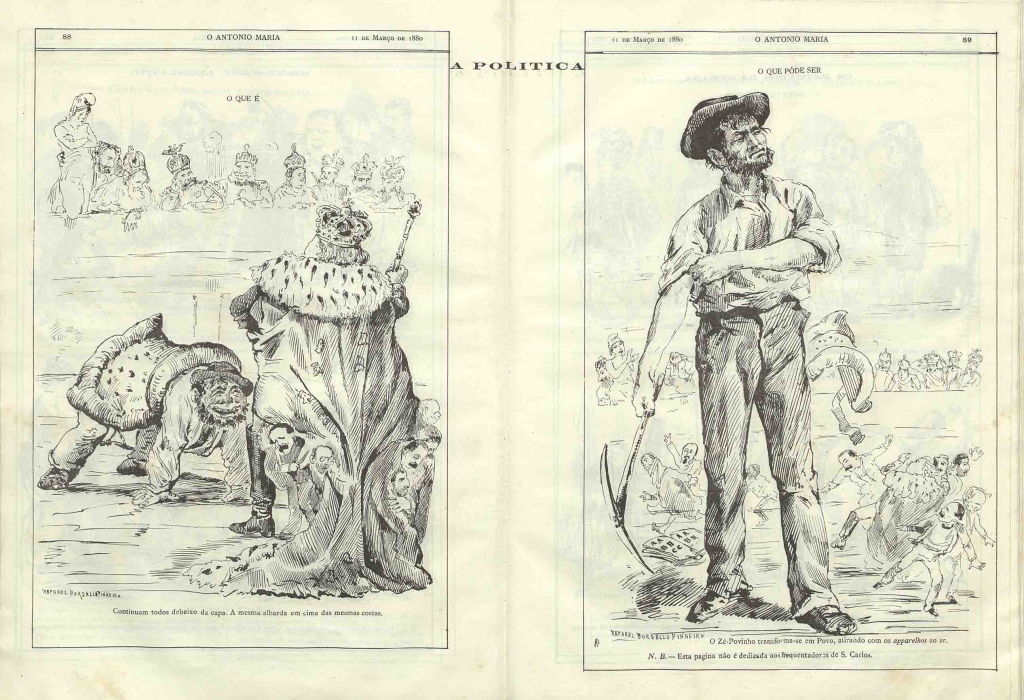

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 11.03.1880

MRBP.GRA..2687

Seven months later Zé is no longer holding a stick in his fist but a pick, an image of what “could be” to match the “as is” image. Here we see him crawling on all fours under his famous donkey saddle straight to the king in his cloak – in which the thieves hide, as we have seen. They hide there and peek out, the politicians of both parties. And they, and the king, would be chased away by Zé’s fury, to the applause of the figure of the Republic in the background. And an alphabet book is highlighted on the ground. “Zé Povinho becomes the People, blowing his fuse. Could be, could be – but isn’t… Although, four years later, a stick finds its way into his hands as the Archangel Michael expelling Mariano (Adam) and Fontes (Eva), both naked, from paradise, parodying the painting by Rafaello Sanzio. Other violent reactions are possible, for example where Zé, on all fours but without the donkey saddle, bites the behind of John Bull(dog) in 1881. Or in 1890, where he, a puppet that always says yes to the government, breaks out of his ceramic encasing to release a young man – Zé Povinho free of preconceptions, his “free vote” in his hand and “armed and ready to fight”. Or a furious Zé protesting the foreign industry invading the country, and kicking it out a year later. He had given another “majestic kick” in 1884, this time kicking the pot containing potatoes representing election promises… And once again the beautiful Republic looks on. Another violent act: dressed as the Marquess of Pombal in the famous portrait, expelling the Jesuits from “free education” (1884), part of Rafael Bordalo’s permanent anti-clerical campaign.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 11.05.1882, p. 148-149

MRBP.RES. 2.4

The artist was not an orthodox republican. Protective of his freedom of opinion, he was capable of having Zé Povinho praise the queen of Spain for having abolished slavery in Cuba. Which did not prevent him from cheering on Portuguese patriotism against Spain in 1886 and 1893. That same patriotism led him in 1883 to protest the thievery suffered by the motherland in the scurrilous deals for the railway link between Lisbon and Spain, agreed upon by Hintze and Burnay, with the Iberian kings shaking hands in celebration. Just as he had protested the invasion of foreign industry, he was also to welcome, in 1891, a domestic industrial exhibition at Porto’s Crystal Palace.

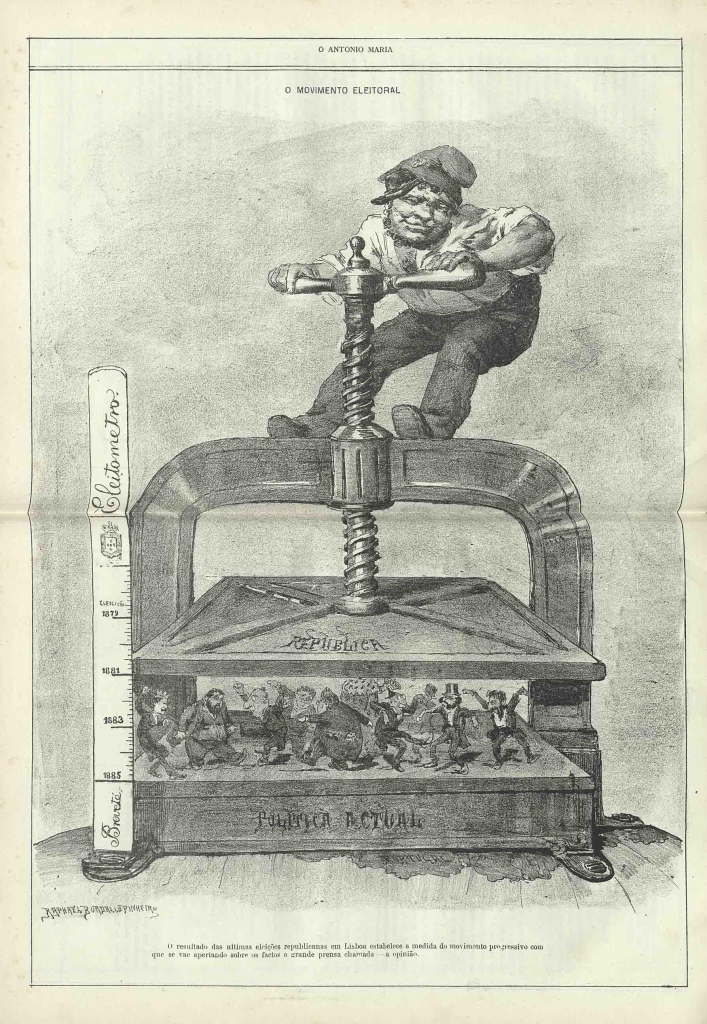

Zé Povinho was perhaps not a republican – but what to do when faced with the “parties of rotation” in a putrid rubbish bin from which emerge party representatives from amongst dead rats and fish heads? Towards the end of the Bordalian discourse, on the pages of A Paródia in 1901, we see the first response to “What can he do?” And from early on, as early as November 1881, we see him avoiding the press called “Republic” that squeezes the whole political class in line with the chronological “electometer” threatening it. This represented the results of the latest “republican” elections, Bordalo writes, referring to the “progressive movement with which the great press of opinion squashed the facts”. On top of his rustic brimmed hat, Zé, tightening the press, reveals a Phrygian cap.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O António Maria, 10.11.1881

MRBP.GRA.2791

In May 1882 he sees many such caps crowning a whole group of statues of the Republic that the establishment members themselves, beginning with King Luís, are unwittingly sculpting. Amongst them, Gomes Leal and Angelina Vidal, committed republicans. Rafael Bordalo keeps himself to himself, sculpting the famous Judge Veiga of the censorship police, and declaring that he “does not make or unmake” the Republic. Zé moves along observing the statues of this “great work” without revealing any opinion, beyond the doubts that he has.

He enumerates those doubts four months later, listening as the Republic speaks into his ear. The king is in the background, on his throne. The political leaders (and Burnay) wander around ghostlike, and the beautiful lady, coming from the skies, speaks into the ear of the indecisive Zé: “What you lack is love of the motherland”. “Huh?”, responds poor Zé. For he is afraid of the wound carved into his chest, the constitution with the crown, being healed. “The pusillanimous patient” always puts the cure off till the next day, with the danger of the wound becoming gangrenous… That’s what the missionaries of the republic – Magalhães Lima, Arriaga – tell him below the blemish-free bust of Henrique Nogueira at their club in 1883. Will he decide to take action? In July 1884 the comparison is clear: the advocates of the Granja constitutional pact jump up and down on his back while the three republican MPs carry him on a podium on their shoulders, under a banner that says “14 July 1789”, a universal reference date. And immediately beforehand we saw Zé Povinho prefer the “red cap” of the republican candidates and their booth of ideas to the claims of the two monarchical parties, which only offer him the usual pot of potatoes. The contest is repeated in December 1885, between the long list of republican candidates headed by Elias Garcia, in the potent hand of the armed beauty that is the Republic, a progress from factory to the fund, and Fontes, who offers him the same pot of stew and thievery in the pine groves of Azambuja, with an arch of flying pounds sterling as the only outlook for the future. “Now, be careful what you decide, oh fool from the margins…”, says the caption. Zé opens his mouth and one eye only, turned to the good side …

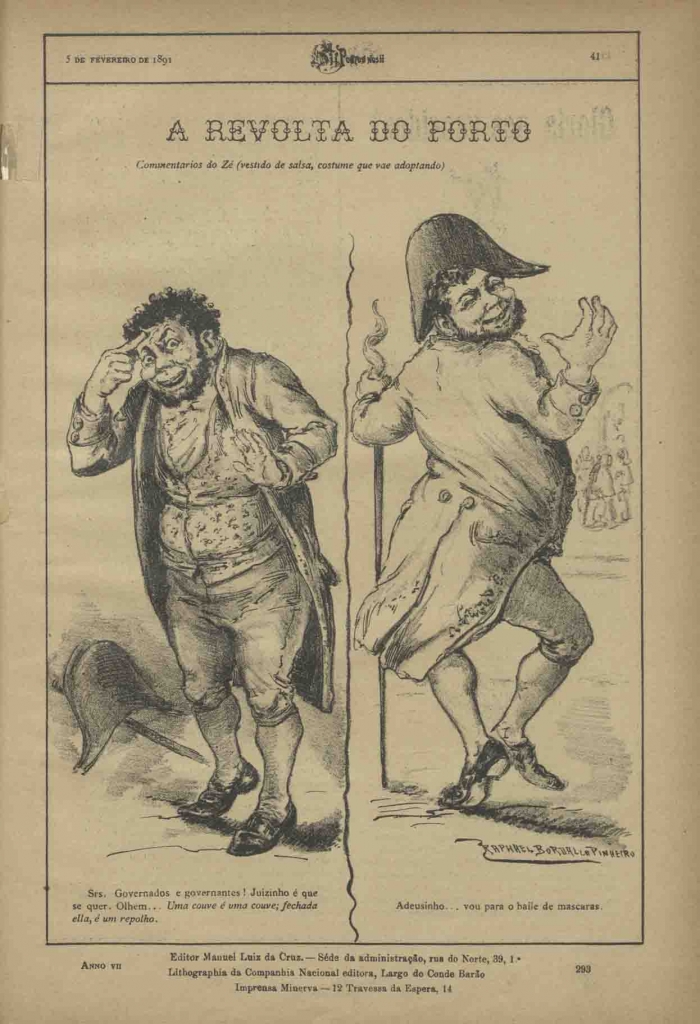

However, the good King Luís cautions him as they play a robbery game. “If you play too hard you’ll be sure to lose”, is the king’s moderate conviction, and it is also that of the anti-monarchical movement not prepared for the attack, as Zé Povinho understands, or thinks he understands. And the tragic test comes, after the British ultimatum, along with the revolt of 31 January. The drawing in the Pontos nos ii edition of 7 February 1891, the last issue before it was banned, is of an ambiguous irony. “Citizens and Politicians! Be sensible…” And he, masqueraded for the Carnival period, joins the other masquerades for the ball of the institutions…

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Pontos nos ii, 05.02.1891, p. 41

MRBP.RES. 3.6

That was the “Porto revolt”, and Bordalo could say no more, beyond reporting on the damage caused by the revolt. Zé awaits his hour, his time. Less than three months later, when Elias Garcia died, Zé Povinho represents the gratitude of a “whole people” at the funeral. There is no humour in his expression as he moves sombrely in the cemetery.

In mid-1903 Rafael Bordalo draws a balance of the life of his hero: “Zé Povinho in History”, which goes from 1807 (though it mistakenly states 1801) to the then present day. The first date marks the flight of João VI (as the court’s withdrawal to Brazil because of the Junot invasion was interpreted at the time) and Zé lies sleeping on the ground of Terreiro do Paço. In 1820 he rises up, pistol in hand, for the liberal revolution, only to lie down and sleep again 12 years later during Miguel’s terror campaign, represented by the background of hanging devices. He rises again in September 1836, not to celebrate victory in the civil war, but for the “vintista” revolution that followed. Then we see him sleeping again when Spanish troops enter Portugal to put down the Maria da Fonte revolution: this was the period of the Convention of Gramido, the year 1851, which is also the year of the Regeneration. Which, just like the victory of Pedro IV, means nothing for him. What does matter is, 40 years later, the ultimatum – a source of great national indignation.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Paródia – Comédia Portugueza, 23.07.1903

MRBP.GRA.1032

Thirteen years later and he is having a royal nap under a leafless Tree of Liberty, with the Judge Veiga up to no good on top of him. These are the ups and downs of a history. “Wait and see”, he says, on the ground, trapped by taxes, below a group of government figures dancing happily in between the nonsensical things they do or the graces and favours they achieve. And these are identified, beyond any doubt, in good caricatures. Zé rolls a cigarette. He has grown old – with white hair, as we already know to expect – by 1903. Three years before and now, for one more exceptional time. All over Europe, from Spain to Russia, social volcanoes are erupting as monarchs and presidents, hoses in hand, attempt to extinguish the fires. In Portugal, because the explosion is moderate – it is Zé Povinho putting out the fire. He does so by urinating on it – discreetly, his back to the viewer – but with a forceful jet.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Paródia, 12.02.1902

MRBP.GRA.1046

But he who is “always waiting” makes a return in February 1902. However, he has changed. It’s not that he has grown old with his creator, which we have already seen. But that he reflects, worriedly, on what is happening: “the government sits and waits, credit is falling apart, the country comes out onto the streets…”

In January 1881, beneath a procession of monarchs, from Afonso Henriques to Luís, dynasty by dynasty, and with little King Carlos hanging off Zé’s head, we see our anti-hero lying on the ground: this is the “Procession of the Holy Kings” and he is sleeping, his head on the donkey saddle. “Will he rise up?”

That was the question at the time. Yes, he rose up now and again, becoming the People – but his thing was really to watch and wait, in this almost final year in the life of his creator.

Mariano’s donkey saddle given to him, although it plays a minor role, is his symbol of life. But, without wanting to get rid of that, he does have another one. A gesture that was created for him in ceramics – the popular “up yours” gesture! The bust of Zé, looking the observer straight in the eyes, no matter who he may be (or perhaps ourselves, each one of us) tells him (or us) what he has to say: to the request for more credit, for the trust the country’s institutions survive on, he answers a definitive No! Up yours! The credit requested of him for centuries, also in the constitutional regime that constituted upon itself, by means of the periodical elections that are a fragile certificate of trust. It’s the only response he can give – folding his arm and turning his back, from regime to regime, period to period, since he was born, and one hundred years later, when a centennial celebration was possible, in a book that got lost at the publisher’s.

What began with a donkey saddle ended with an obscene gesture, as was written at the time. It is between these two symbols that one must interpret the importance of this one-of-a kind national hero, for reasons of the Portuguese historical, economic and cultural, and naturally, political way of being; and for reasons of the inherent necrosis of the government or governments. That is why the Republic was unable to alter its centuries-old structures; neither the First Republic nor the Second, with the censorship that took place between the two serving as a mitigation factor for the latter. Zé Povinho – who, what? A subject or object of national life that in Rafael Bordalo’s lifetime did not evolve, even if it progressed more in terms of population figures than the development of its people. “Always the same”, as Zé would say: progress as a crab, education as a donkey… Between what Eça wrote and published or left unpublished and Fialho, the city grew from the Public Promenade to Fontes’s fancy Avenue. The costumes may have changed on the women, or ladies, and on the men, or gentlemen, seeing how bourgeois recognition was so important to them. But the structures did not, despite Fontes and his “Fontism”; he could not do more, for reasons of heritage and ill-gained possessions. If one link could be established, it would be between Fontes and Zé – both victims of the motherland they were born in, one an engineer, the other a rural farmworker.

Rural in the worst way possible – coming from the suburban belt between the city of the others and the country he no longer was part of: the farming gardens of Porcalhota that feed the city and provide its Sunday leisure activities of fado and red wine… Today, Zé Povinho would live in the slums (or perhaps lives there – as sociologists would argue, backed up by data on the transformation in terms of taverns and drugs, unemployment and satellite TV…), and working in a factory that did not exist in his day; today there is what there is. “The People was no longer Zé Povinho”, said João Chagas, in the early 20th century, the “Paródia” period. But he, a republican (and Parisian) could hardly say anything else without contradicting himself. The times never became as tumultuous as Ramalho had thought 20 years earlier. Romanticism continued to reveal itself in the gentle customs, which, if anything, were now more refined.

Whilst, in the hiatus of time collected or non-existent that was the Estado Novo regime, with Fontes reincarnated as Salazar with the reactions of Cabral, Zé Povinho gradually disappeared from the newspapers and the theatres, it was not because he had ceased to exist. But because he could not show his inconvenient or subversive presence, as he represented what most hurts in institutional critique: disrespectful, anarchical humour.

But still, he waited – for a miracle, a lottery win to make him rich, as so many others hoped for as the only way out of their endemic misery, or for a Godot who was to come, or perhaps not, as the night descends, from time as it passed.

Lithograph

unsigned/undated

Published in Pontos nos ii, 03.08.1889

MRBP.RES.3.4

Joseph Prud’homme, a product of French bourgeois culture, died with the same historical period he was born into a quarter of a century earlier – the reign of Louis Philippe. And John Bull, an emblem of British imperialist culture also died with Queen Victoria, losing his raison d’être and all his vainglory with the future loss of the lands conquered around the world. And Uncle Sam, the symbol of the United States in a different and potent form of imperialism, can now no longer be evoked beyond the war efforts in 1917, doing better to lead a covert existence throughout the 20th century as the more than suspect protector of American and European territories and Middle Eastern lands in the oil crisis. The three symbolic western figures all enjoyed the lifetimes the political philosophy could afford them in the struggles between more subtly defined geo-political interests. And what period would best suit our Portuguese Zé? Dismantled by the Estado Novo regime, his colonial, monarchic and, logically, republican patriotism could not be evoked to argue for the wars in Africa – at least not with a minimum of judiciousness, as ideas of decency did not enter into the matter. And in 1974, summoned by the admirable pencil of João Abel Manta, he could, or should, only advocate understanding between white and black – after all, we had all been blacks and treated as such for the preceding half-century in the country. Or perhaps advise, like in the confession box, the new heads of the reborn political parties not to fleece him (fat chance!) over another half-century of silence, policing and misery…

If, in the uncertainty of that heady period, what with the Americans and Soviets, another ingenious character could be created, by another Sam – Ricardo the Guard, the original spokesman for common sense in the whirlwind of absurdities – to great success in newspapers and with the public, that figure could only be intellectual, active in the sphere of sophisms, which was not Zé Povinho’s, whose realm was more that of plain speaking. Rafael Bordalo’s creation resisted that trend – “always the same” – sleeping or waiting, he did not know, does not know and will never know what’s what. He draws his perennial strength from precisely that identity – true to himself, whether he is in a suburban farm or shantytown, cheering on Benfica football team or protesting the ever-increasing cost of life – a spectre hovering above the heads to which we are bound.

The reader of the ten thousand pages produced by Rafael Bordalo over a third of a century that was decisive for the modern definition of the motherland, will discover in every corner a Zé Povinho who anecdotally and circumstantially represents, exhibits or animates a case or a problem. And as, the reader is of the here and now, as it must be, that encounter is updated as if it were happening now. Zé can outdo the thousands of commentaries and opinion writers of today simply by doing what he has always done. The political figures of the early 21st century – all of them, old and young, every Tom, Dick and Harry – have already been caricatured by Rafael Bordalo and encountered by Zé Povinho. No more, no less! For this reason, we can call the most important Portuguese artist of the latter half of the 18th century, along with his brother Columbano and Malhoa, a triad of national culture, inside and outside the land, in the city and the country, “the Portuguese Real McCoy”.

… And when we get nostalgic, as Zé’s contemporary “O Desterrado” [The Exile] by Soares dos Reis reminds us, with explanations and apologies, Zé Povinho can always counter with his firm and definitive gesture. It’s nostalgia you want? Up yours!…

Lisbon, January 2004

Faience

Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro

1904

MRBP.CER.375