Drawing for laughs: holding a mirror to bourgeois society

By Raquel Henriques da Silva

Nothing else survives: the authority derived from age and experience, birth or genius, talent or virtue, all is denied (…) When steam power will have been perfected, when, together with the telegraph and the railways, it will have made distances disappear, there will not only be commodities that travel, but also ideas which will have recovered the use of their wings (…) The invasion of ideas has succeeded barbarian invasion; the civilisation of today, decomposing, melts into itself; the vessel which contains it has not decanted its contents into a second vessel; the vessel itself lies shattered.

Chateaubriand, Mémoires d’outre-tombe, 1841

Prologue: Europe in the Latter Half of the 19th Century

In the schematic reflection always imposed by historical judgement, the 19th century represents, in the West, the affirmation and spectacular triumph of industrialisation. In other words, the economic model based on the mass, machine-based manufacturing of consumer goods.

That economic revolution took place in a specific social and political framework that undoubtedly facilitated it and was facilitated in turn by it: the “bourgeois society” which, before the term became a standard designation rendered increasingly devoid of specific contents, means the existence of liberal governments, with separation of the diverse areas of sovereignty, subject to democratic vote, and a strongly hierarchized social organisation in which power and money coincide in what is known as the dominant group. Through diverse channels, which today’s laws no longer totally provide for, recognition of the nobility, either by birth or acquired, remained open, bringing with it certain privileges.

For these reasons, the 19th century European bourgeoisie was a complex social mixture that, at the top, aspired to aristocratic status, facilitated by money and/or birth.

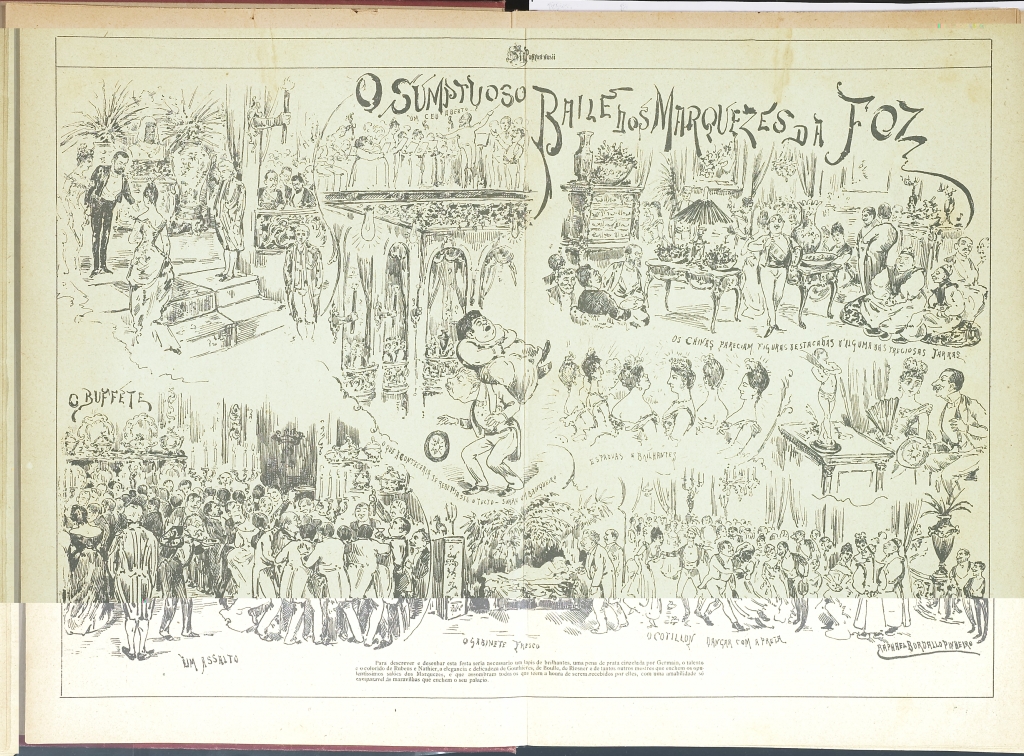

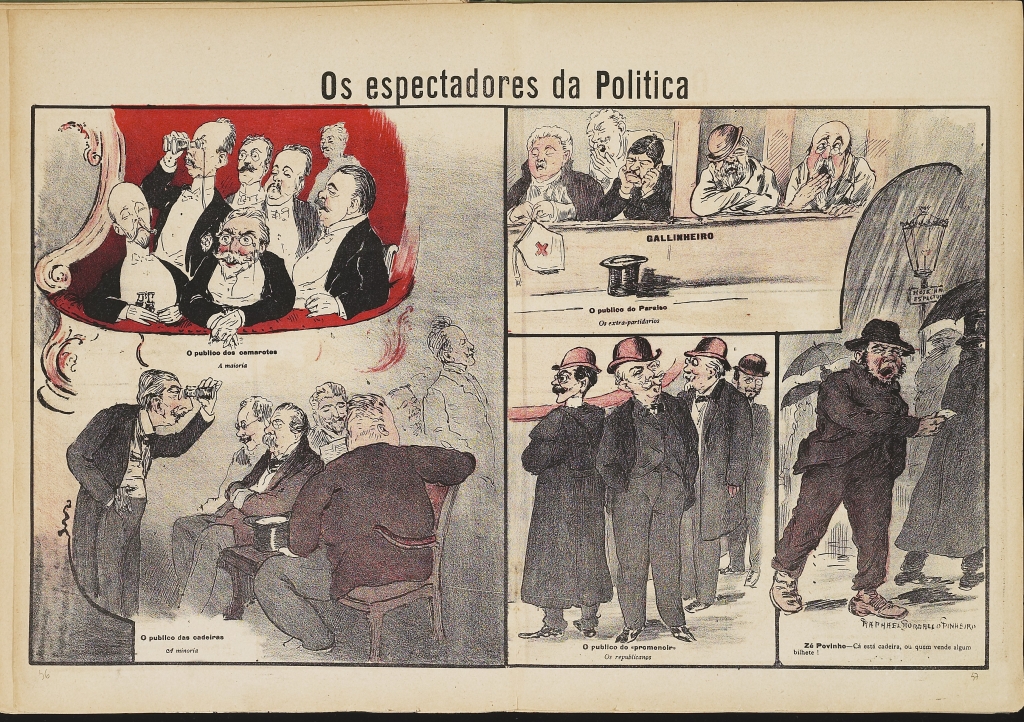

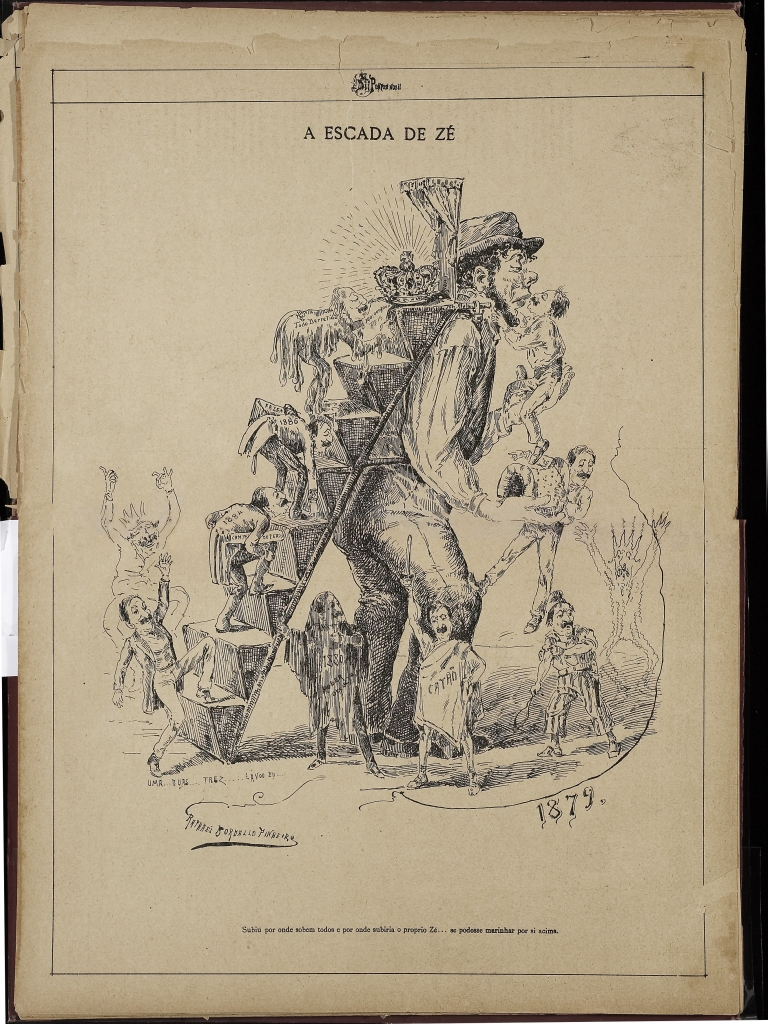

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Pontos nos ii, 05.01.1889, pp. 4-5

MRBP.RES. 3.5

One should bear in mind – as it is decisive for understanding how similar these times were to ours, though also very different – that the latter half of the 19th century saw exponential growth in the number and diversity of noble titles, which were paid for by the interests of the State and, in certain cases, granted for the duration of one life only, meaning they could not be inherited.

Thus, being a “baron” or a “viscount”, a “count” or a “marquess” in the 1800s in Europe was an insignia that did not necessarily equate to having a genealogy. In order to assert oneself, one needed the social status: that required, in almost all cases, wealth, no matter where it came from (the instances of titles granted on merit only were numerically insignificant ). A noble title also called for a certain degree of political commitment at the local or national level and some “Christian charity” work, as practised at the time, in aid of the poor or, revealing another ambition, in support of culture. These actions aimed at aristocratic affirmation generated and nourished a system of “courts” consisting of supporters and dependants, and were manifested in exceptional recreational and cultural consumption: the purchase of more or less princely houses, travel, theatre attendance and the purchase of works of art and antiques.

One should also note that the governments of bourgeois states, regardless of whether they were one of the predominant monarchies or the very rare republics, were dependent on this social class, thanks to their right to a vote that we today can only consider rather undemocratic, given that it was not given to women or those classes that did not contribute to the system with significant taxes. In other words, the European democracies of the day were, to be more exact, very exclusive male plutocracies.

As for the numerous royal courts, which dictated fashions, behaviour and representations, they were one large extended family thanks to extensive selective marriage policies. In Portugal, for example, Maria II, the first liberal monarch, married the German prince Ferdinand of Saxe Coburg Gotha, a cousin to another German who married the powerful Victoria of England. Their two sons who became kings, Pedro V and Luís, married Italian princesses, Stefania and Maria Pia, the latter a daughter of King Victor Manuel. Their grandson, King Carlos, married Amélie of Orleans, the daughter of the Count of Paris, who, for monarchists, continued to represent the possibility of a return of the monarchy to France.

The monarchs of 19th century Liberalism reigned and did not govern, in line with the British parliamentary model that had successfully established itself there in the 17th century. But they were enormously important: not only because they chose the ministers that made up the governments, but also, and above all, because they transmitted to society as a whole values of continuity of the “old regimes” that the revolutions in the early phase of the century had theoretically shut down. Because of this, the monarchs were symbols of conservatism and attachment to the past that made them the preferred target of the various sectors of the opposition. Nevertheless, a number of figures from the main reigning houses of Europe were drivers of economic, social and cultural progress, be it through personal commitment or through the symbolic way in which they represented modern interests. And so it was in the case of Portugal. One has only to recall the patronage and generosity of Ferdinand of Saxe Coburg Gotha, who built the Pena Palace and fought to protect the most important monuments of the motherland, as they were then called. Or the cultural vein of Pedro V, who encouraged the organisation of international exhibitions and commissioned the Estefânia Hospital, specialising in children’s diseases. Or the interest in the arts and sciences shown by Kings Luís and the unfortunate Carlos, who was a painter and oceanographic researcher.

Photograph Proof, b/w

Early 20th Century

Lisbon Municipal Photographic Archives Number: ACU001461

The bourgeoisie in power in this increasingly wealthy Europe was harshly contrasted with the scandalous poverty of numerous sections of the population throughout the 19th century. In the country (where the majority still lived), the ongoing agricultural revolutions – aimed at achieving mass production to supply the cities and for export – put an end to the traditional expanses of small holdings, leading to unprecedented migration that fed the increases in the urban populations at home, and above all, the growth of the countries in the Americas which, thanks to political independence gained earlier in the century, became increasingly important as sources of raw materials and stable consumer markets. In the case of the most prosperous of them all, the United States of America, emigration from both Europe and Asia consolidated the country which, from the 1870s onwards, took its place as the most dynamic society in the international context, at first in economic and technological terms and later in the fields of science and culture. In the case of Portugal, emigration above all form the poorest rural regions of Entre Douro e Minho favoured Brazil as a destination. The prosperous former colony had proclaimed independence in 1821, choosing as its emperor the heir to the Portuguese crown, King Pedro, who briefly sat on the thrones of both countries during a tumultuous period that included civil war. The demographic, economic and social importance of that emigration was one of the most important aspects of Portuguese 19th century history, facilitating, first and foremost, affirmation of the identity of the new nation that assumed its Portuguese origins as a positive peculiarity in the Latin American context. For that reason, the main Brazilian cities were stimulating places of consumption of Portuguese culture – from literature to the fine arts and from journalism to the erection of monuments. In addition to this, the powerful Portuguese communities in Brazil acted as patrons for almost all cultural and social activities in Portugal at the time – from newspaper and magazine publication to the building of schools and the construction of the Camões monument in Lisbon’s Chiado quarter.

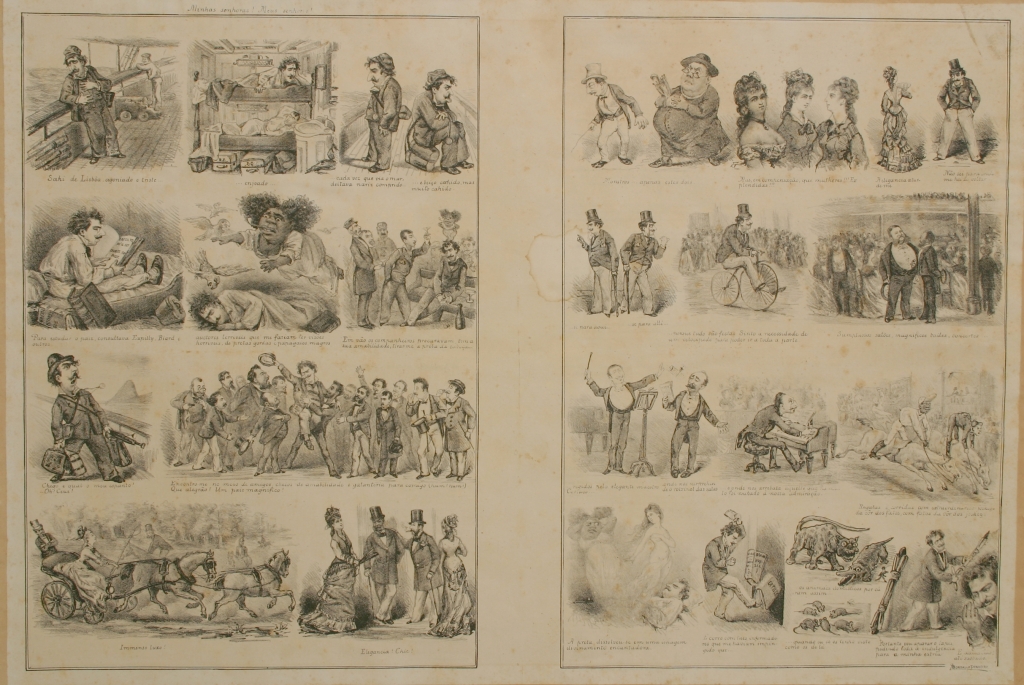

Lithograph

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O Mosquito, 11.09.1875

MRBP.GRA.216

Also, the success of emigration to Brazil (based, obviously, on the lack of success of so many at home) gave rise to the particular figure of the brasileiro torna viagem or Brazilian returnee in late 19th-century Portuguese society, parodied in the novels of Camilo Castelo Branco and, more generally, on the pages of newspapers in both countries, including by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro. However, in many cases the “Brazilians” played an essential role in local and regional development, both in terms of investment and also in terms of social representation and urban cosmopolitanism. But the poor in Europe in the throes of industrialisation and in control of the world markets (including the Far East, India and, increasingly, the new African colonies), were not just the country folk evicted from their lands and forced to work for the market. They were above all the new urban proletarians, factory workers including women and children – dispossessed of everything, badly paid, badly nourished and badly housed.

This unprecedented situation – that showed the brutal side of the nascent industrial capitalism – was the origin of new social and political confrontations, encouraged by the theories of Marx and Engels. They proclaimed the inevitability of communist systems, but also advocated the anti-capitalist reforms of Proudhon and various types of anarchists – in conjunction, or not, with the diverse trade union families.

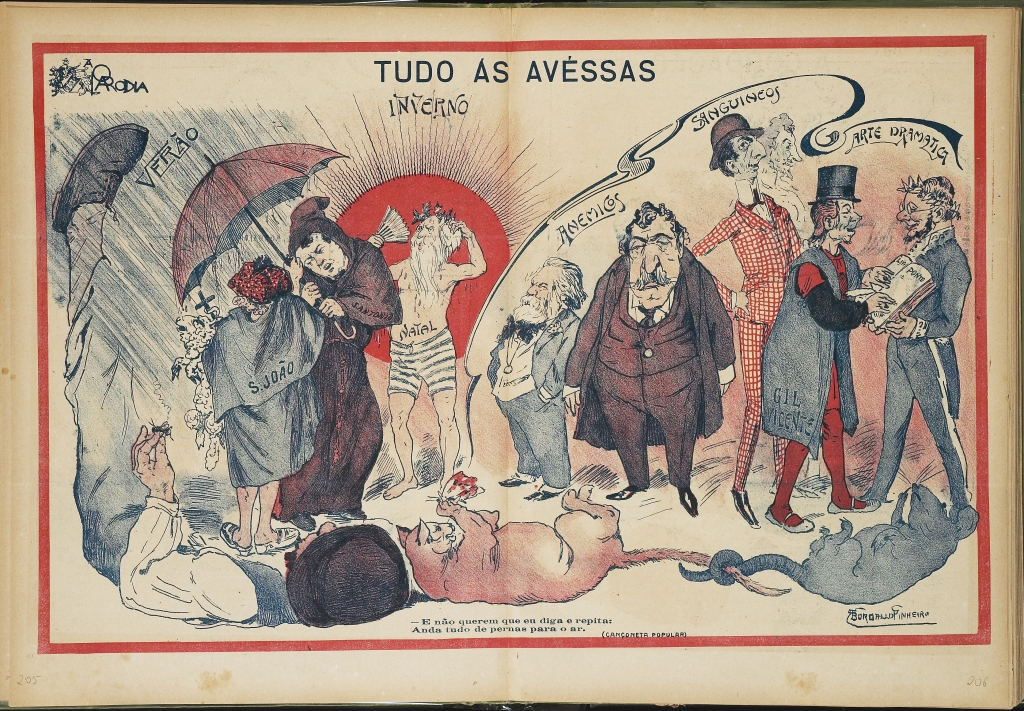

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

A Paródia – Comédia Portugueza, 25.06.1903, pp. 4-5

MRBP.RES. 1.4

From the mid-century onwards, industrial workers gradually achieved better social status in terms of working hours, the right to strike, sickness welfare, housing and education. In addition to assistance from the unions, these advances were often supported by charity or civic association initiatives. Nevertheless, the revolutionary atmosphere remained a threat for governments and those groups in power. The climax of this trend, in western European history, was the Paris Commune of 1870, which imposed popular government by means of terror, only to be brought down itself by terror. Until the triumph of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 in Russia, such an extreme situation was not to be repeated. But the late 19th century was a time of permanent agitation, also marked by growing political strife between the major European states, eventually leading to the First World War. It was in this climate of confrontation that Portuguese history between the Ultimatum of 1890, the proclamation of the Republic and its permanent crisis can be situated[1]. This is not to say that the period outlined above was an unhappier one than the present day. I do not believe so, although there was more poverty and greater social inequities, more uncertainty and the permanent risk of death as a result of the general misery and lack of medical knowledge and treatments. Beyond the passions and confrontations that so many exceptional people became involved in, we need to return to the field of culture to recall the brilliance of Europe in the latter half of the 19th century, the century of Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, who not only intensely reflected its contradictions but also continues to provide insight into it through his vast oeuvre.

Urban Culture: Permanent Innovation and the Cult of Technological Progress

It is neither possible, nor perhaps necessary, to list here all the extraordinary advances we owe to the 19th century in the most diverse fields. In the fields of science and technology, someone who was born before the middle of the century and died at the beginning of the next, as indeed the case with Bordalo, witnessed the establishment of the railway (the first line in Portugal dates from 1856, while in England the railway network was begun in the 1830s). It was the symbol of a new civilisation, rapid and integrating, and represented the generalisation of iron and machinery, which was also reflected in transatlantic passenger ships.

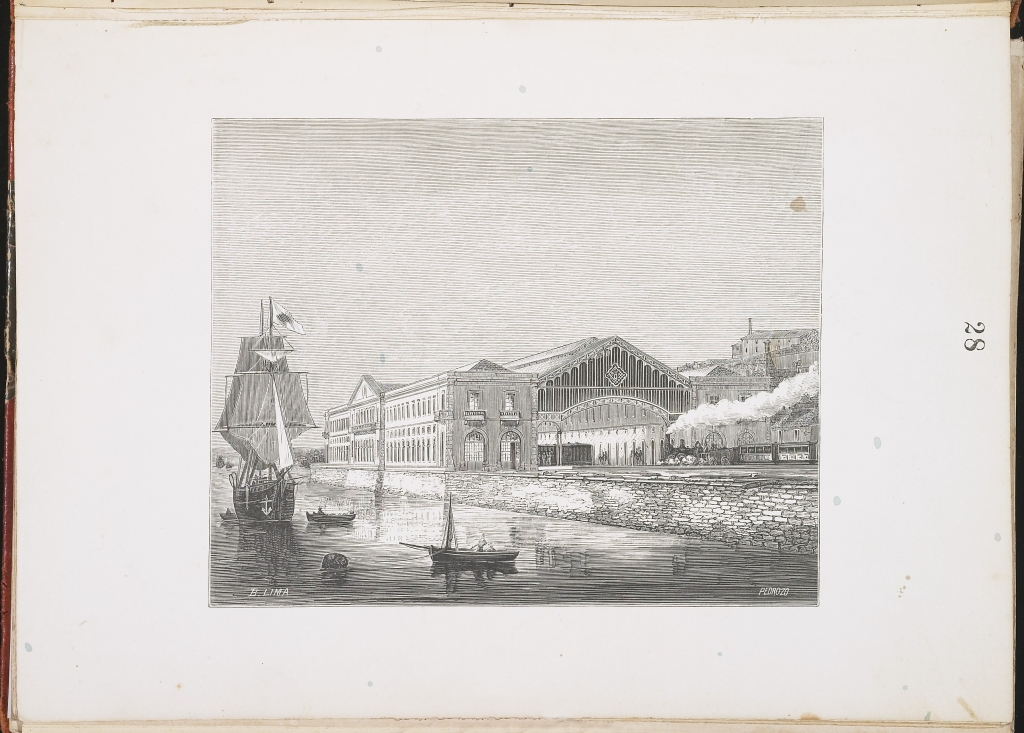

Lithograph

B. Lima; João Pedrozo

In Universo Pittoresco Jornal de Instrução e Recreio, Vol. 2 1841-1842

MC.GRA.198.35

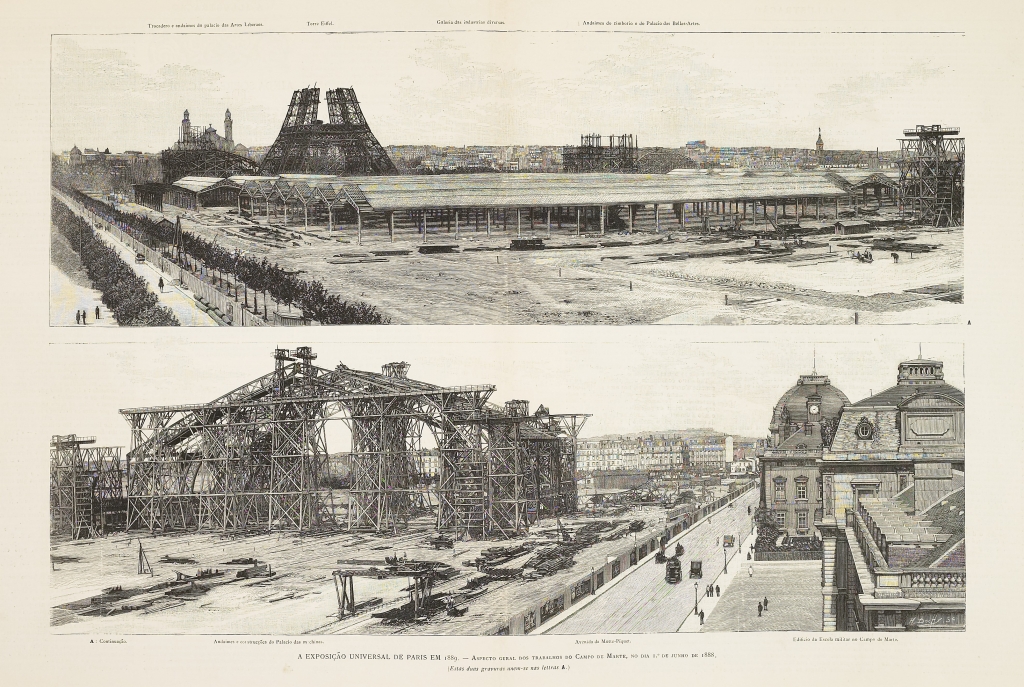

In the architecture of the day, trains, railway tracks and stations were modern images that promoted iron as an effective material, which, when combined with glass, gave rise to what became known as the “crystal palaces”, the first of which was opened in London in 1851 to house the first Great Exhibition in world history, which was visited by thousands of people. Before the end of the century, in 1889, it was Paris’s turn to amaze the world with its own exhibition, celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution and establishing the Eiffel Tower as its symbol. Likened to a vulgar, gigantic factory chimney by many people of the day (including important writers and artists), the tower was to become one of the most popular monuments of the modern age, an affirmation of a radically new aesthetic that valued the beauty of the materials themselves free of all the academic, neo-Classical ornamentation that was still in fashion.

Etching

A Illustração, vol. V, 1886, p. 216

MRBP.RES. 26.5

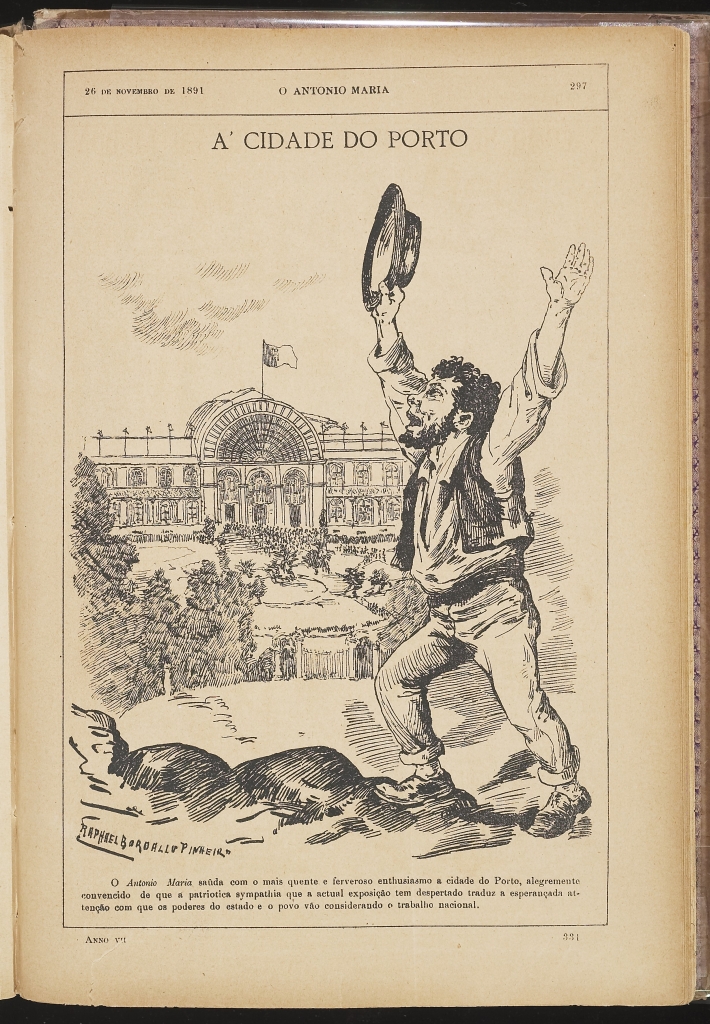

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 26.11.1891, p. 297

MRBP.RES. 2.7

This new architecture, based on transparencies and technological lightness, asserted itself in bridges, factories, the first urban department stores (the precursors of our shopping centres) and the covered galleries in many of the most important capitals in Europe and the Americas. In opposition to neo-Classical architecture, which continued to be used for particularly representative facilities, it revived the values of verticality and lighting of the Gothic aesthetic and was a decisive influence on Art Nouveau, which emerged at the turn of the century, heralding Modernism.

Before the end of the century, electricity began to replace steam as the essential means of power, providing the lighting for city streets and home interiors. Thus, a revolution was begun that has continued to the present day, freeing us from the restrictive cycle of day and night. Electric motors became the instrument of profound change in urban public transport, giving rise to the electric trams and mechanical elevators to which Bordalo, and all his contemporaries, rapidly adapted. At the end of his life, in the early 20th century, he also witnessed the automobile and had an idea that the aeroplane would soon take off from the pages of Jules Verne’s works of fiction (Bordalo was a great admirer) and fly into reality. He also used the telephone and domestic elevators, the increasingly efficient post office resources, the first vaccines that announced the future importance of chemistry and biology and initiated a new cycle in human existence.

Photograph Proof, b/w

Joshua Benoliel

1913

Lisbon Municipal Photographic Archives Number: JBN003532

Notwithstanding this non-systematic inventory, one must also stress that the technological and scientific fervour of the late 19th century also gave rise to new attitudes as to man’s own existence. Some were paradoxically marked by philosophical and artistic pessimism, contrasting the possibilities opened up by progress with the social misery that seemed to grow ever greater, or as was the case with Chateaubriand cited in the introduction, with the crisis in the inherited cultural models. Bordalo belonged to a different ontological family: he was an innate optimist, a doer with a passion for the opportunities technology brought with it. He experimented with them in two fields: the written press, which had a background of graphic art and writing and typographic work, in which he excelled; and in artistic ceramics, from his small and innovative factory in Caldas da Rainha (in partnership with one of his brothers), where he sought to adapt the popular clay pottery manufacturing processes to a more refined and industrialised aesthetic that incorporated the essential values of craftsmanship.

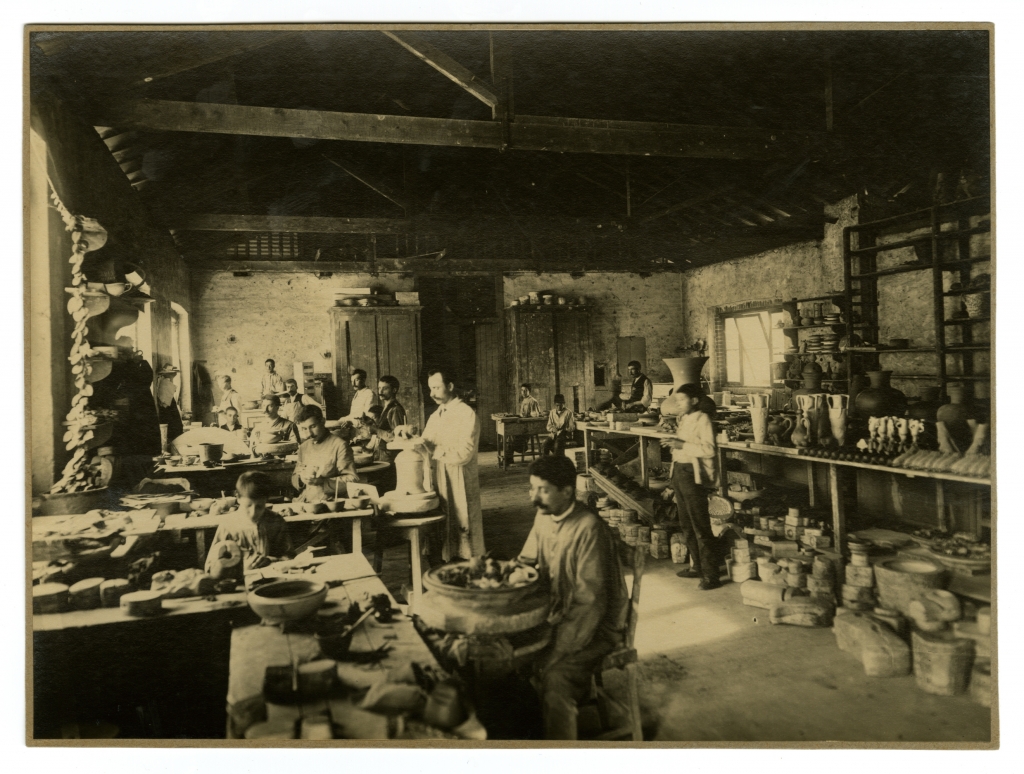

Photograph Proof, b/w

s/d

MRBP.FOT.690

As a very rare example, for Portugal, of the humble boss, with a readiness to take risks, his goal was never wealth but personal realisation, as well as that of the friends and employees closest to him. He was never discouraged by the often considerable economic and technological setbacks, nor did he forsake his love of experimentation for a more cautious existence. He was, without a doubt, an artist. One who came up with his own creations, but who knew that the arts have their own challenges, based on the traditional know-how of the artisans and, increasingly, the efficiency of the machine.

Photograph Proof, b/w

1888

MRBP.FOT.716

A man of his time, a progressive and convinced humanist, he knew that art and technology were not contradictions in terms but two clearly defined phases of the modern creative process. It is my conviction that if Bordalo had not loved technological process so much he would not have been the ingenious author/co-author and publisher of several newspapers, magazines and albums he became. Nor would he have invented “Caldas ceramics”, its graceful blend of tradition and innovation very much in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement that defined contemporary design at the time.

But there was one other essential factor: the artistic climate in which liberty had established itself as the absolute queen.

Anti-academic Struggles: the Arts and their Artists

In referring above to the innovative paths architecture took in the latter half of the 19th century and the symbolic image of the Eiffel Tower, I also mentioned how hostile the critics of the day, even the most qualified ones, were to this revolution in the arts. That hostility, reflecting what was known as “bourgeois taste”, was a response to one of the most interesting aspects of urban culture, that which valued, in particular, inventiveness and change. Indeed, it was this form of confrontation that gave rise to the figure of the rebel artist who was misunderstood and, in the best examples at least, a genius. A figure we still have today.

There were, however, very objective historical reasons at the root of this confrontation. They have to do with the profound changes to the process of art production and the generalisation of the consumption of art. Simply put, one could say that, during the Ancien Regime (the period of absolute monarchies and the dominance of religious values), artists worked for the “court” and the “church”, in other words, for elite institutions and groups. This, of course, does not mean that the great works of art of this period did not have a more widespread impact on society. But the limited sources for commissions were reflected in considerable restrictions in iconographic and aesthetic terms.

Throughout the 19th century, and above all in the latter half, artists gradually created a more widespread and open market for their work, where, in accordance with capitalist economic ideals, art became a commodity like all others. In order to stand out in a competitive market, an artist had to create his own conditions for his work, win over publics and establish himself over thousands of other works of art.

In the field of the fine arts, painting (along with literature and music) was the most advantageous medium for manifesting and consolidating the ongoing transformations. As opposed to architecture and even sculpture, it gave rise to new elementary techniques. Those techniques continued to liberate art from its old constraints. One example is the relatively low cost for the production of paper and canvas, as well as graphite and brushes. The widespread availability of paints in tubes provided a diversified ready-to-use palette. The railway networks also provided the indispensable opportunity for artists to easily get out of the academies and “into the countryside”, assisted by bicycles which also served to transport a form of mobile studio that could be mounted where the motif was – i.e. outdoors and in nature.

Photography, which had been invented in the 1830s and almost immediately became a widespread phenomenon, also played a role in taking painting out of the academic context and stimulating creativity in an area that, it was thought, would remain free of mimetic competition, as photographers had claimed it for themselves.

Finally, a growing interest in artistic careers, as well as a greater understanding of the artist and his work based on romantic ideals – the proclamation of individual liberty and the right of self-expression – completed the picture of a new approach that challenged the teaching models in the fine arts academies. The academies continued to view the ideas of beauty and the various artistic processes from within a neo-Classical aesthetic framework that increasingly had less to do with the real-life experiences of their young students.

So even before Gustave Courbet’s revolutionary move in 1855 – his presentation, in an individual exhibition set up in a pavilion close to the entrance to the World Fair, of the very paintings that said exhibition had rejected, under the title of “Du Réalisme”[2] – the century had already been traversed by an anti-academic fever that was fed by the nascent specialised criticism of art lovers, collectors and the artists themselves.

The consequence of all this simmering under the lid was an intense new lease of life for the arts, with fundamental critical and aesthetic confrontations. By the end of the century an idea had formed across Europe that the best art was produced outside the academies and the more institutionalised circuits of dissemination. But more importantly, a progressive fragmentation in terms of aesthetics, techniques and iconography also took place, contributing to the notion of “truth in art” losing its hitherto incontestable models.

In terms of the iconography, the new art also definitively challenged the academic rules. Firstly, there was a general reclaiming of the landscape as its own artistic genre and not just the static, invented background (i.e. copying prints) of historical painting. Painting itself had been in a crisis that it survived above all thanks to decorative work in public buildings, often blurring the lines between conventional art and the decorative arts.

As part of new social dynamics, stimulated by the climate of constant invention and rejecters of the schools and the heritages, the artists established their work at the uncertain heart of reality. By means of the portrait, the landscape painted en plein air and the depiction of new aspects of urban life, painting was able to renew itself, reflecting concrete places and people which, in the Impressionist aesthetic, were to merge with the movement itself. The other side of this urban art was expressed, at the same time, in Symbolist iconography, rejecting in life the extreme expression that only existed in dreams. Whilst the study of the artistic movements at the end of the 19th century is not the object of this text, it is of interest to highlight this commitment to the present. Although it did not unite the various fields of artistic expression, it did definitively establish the little daily life story at the national and even routine level. For this reason, caricature and the cartoon were to take on new importance.

The Importance of Laughter: Caricature and Cartoon as a Social Weapon

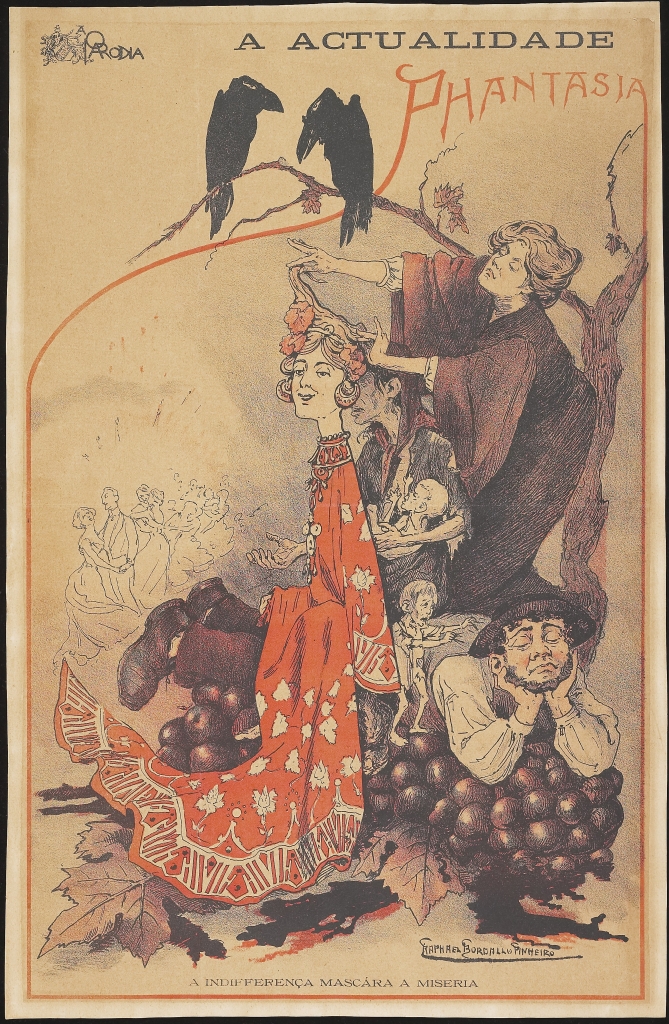

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Paródia, 26.06.1901

MRBP.GRA.2026

Bourgeois society, as defined at the beginning, was an extraordinarily good target for parody. Its values in the latter half of the 19th century moved, with a certain degree of uncertainty, between the desire for noble social status and the petty tasks required by capitalist ideals. Governments now aimed to serve the “common good”, but regularly disregarded such noble goals to protect the interests of the more powerful. Wealth creation grew like never before, but not to the benefit of the huge number of urban paupers, who were now freer and had more demands.

These contradictions reflected differences and conflicts that, one could say, had always existed. The difference is that, major constraints notwithstanding, there was, in most of European and American countries of the time, unprecedented liberty, an interested public opinion and growing circulation of information.

One of the most important revolutions that was ongoing at the time was the general provision of school education, constantly reducing the numbers of illiterate. The implementation of school education did not mean an increase in wealth, just as the circulation of information did not mean bring about significant change in terms of corruption or injustice. But it did facilitate the consolidation of the middle classes who were predominantly urban, more educated, more demanding and, of particular interest for this text, read an increasingly high number of newspapers and magazines.

As we live today in a constant whirlwind of information and news, it is not easy to understand the beginning of this cycle. Books, magazines and newspapers were still relatively rare, although they did circulate to a degree that would surprise us. They had their loyal audiences, which they constantly expanded, for which they were precious instruments of learning and diversion

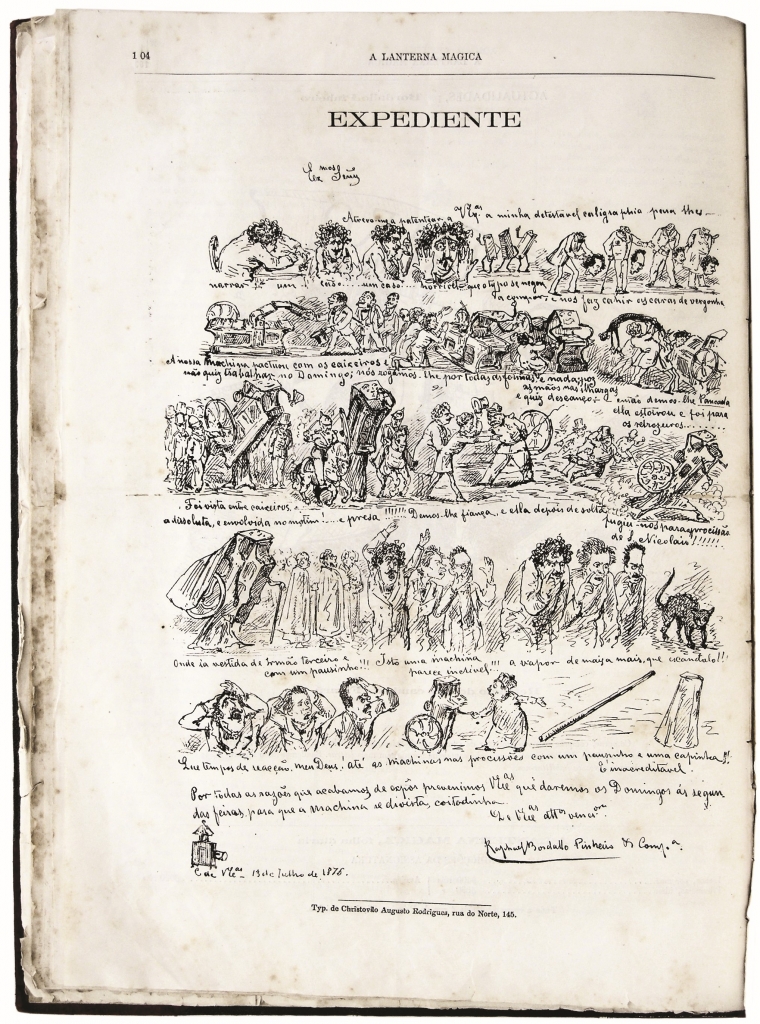

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Piinheiro & Compª”

Published in A Lanterna Mágica, 14 July 1876

MRBP.RES.18

Some of the technological innovations mentioned above played a very important role in the expansion and consolidation of the written information networks, the only networks that enriched direct conversation. One example is the railway, which allowed for the regular and relatively rapid transport of the issues in their high numbers. Typography also benefitted from the progressive trend towards machine production, using a great diversity of types of paper. A comparison between the newspapers of the first and second halves of the century shows that graphic design was now an established thing (although it was not known by that name) and that the dense body of texts was now combined with the freer and more appealing spaces reserved for illustrations, prints and drawings, before photography began to assert itself in newspaper printing towards the end of the century. This was the heyday of the lithograph, a printing technique born in Britain in the late 18th century and disseminated with extraordinary inventiveness in France during the reign of Louis Philippe, from 1830 onwards, particularly through the work of Daumier[4]. The culture of the image, of which we are the direct heirs, was asserting itself in the large cities that were more and more influenced by international trends.

In the hierarchy of the fine arts, indeed today and in the 19th century, the drawing only enjoyed an independent status amongst the specialised elite. For the general public, and even for museums, the drawing was a poor cousin of painting, architecture and sculpture. And when it is used to serve a specific narrative purpose, it enjoys even less recognition. This was the case for the cartoon and caricature, despite the fact that their great social and political impact was generally recognised.

However, in the frenetic and diverse world of the arts in the 19th century, caricature or “humoristic drawing”, a common designation at the time, was extremely important. One should bear in mind, to cite only the most relevant cases, that Francisco Goya (1746-1828) had revolutionised academic printing in the early 19th century. In his series The Disasters of War (which dealt with the Napoleonic invasions), thanks to the expressive freedom of his drawing and the impact of the social and moral critique of his images, he initiated a new form of art in which the smile becomes a grimace and tragedy unfolds under the crude outlines of comedy. Whilst it is certain that the impact of Goya’s printed work had a lot to do with the fact that he was also an exceptional paint, one should nevertheless point out that the technical, aesthetic and stylistic option for drawing and printing was one of the most appealing aspects of modernity.

From the 1830s onwards, the artist who stood out most in this field was Honoré Daumier (1808-1879). The fact that he only ventured into the worlds of painting and sculpture episodically has hindered his full recognition as one of the pivotal artists of the century in the more conventional histories of art. His contemporary, Balzac, said that Daumier was the “Michelangelo of caricature”[5].

Working primarily as an illustrator and caricaturist for the leading French satirical publications (which were widely read in all of Europe), Daumier was one of the most inventive artists of 19th century modernity, above all thanks to the expressiveness of his drawing which, while appearing to describe the world and the things, in reality recreated them in synthetic, stripped-down form. For this reason, he is close to the realistic aesthetic of Courbet but at the same time announced many of the artistic values of the Impressionists, first and foremost Edgar Degas.

Daumier’s importance resides not only in his innovative style but also in the way the formal inventiveness informed and reinforced the inventiveness of his motifs. Profoundly sceptical in relation to the society of the day, he defined output social criticism and constant denunciation as the main objective of his artistic. He pursued king and presidents, ministers, members of parliament, judges and capitalists and contrasted their lavish power with proletarian misery tinged in dramatic nocturnal colours. One reason why van Gogh admired and was inspired by him.

Contrary to the typical art and artists of his day, Daumier was not in the least concerned with creating a “life work” ready to be put in a museum. He devoted himself entirely and exhaustingly to drawing the history of his times, assuming, with uncommon ethical dimension, an artistic project in which drawing and painting, alongside the word, served to depict the dreams and failures of the young bourgeois society. It is this generous man and very talented artist we can evoke in seeking to understand the work of the Portuguese artist, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro.

Portugal in Regeneration: Political Peace, Communication Channels and Parliamentarism

In political terms, Regeneration is the designation for an historical alliance between two of the leading political parties in Portugal – the “Historical” Party and the “Progressive” Party. In 1851, representative of the two parties, under the counsel of Alexandre Herculano, decided to outline a common platform of governmental understanding with the aim of ending a period of confrontations. Those confrontations, born out of the Liberal revolution of 1820, had already given rise to a civil war that was continued, after the declaration of peace, in diverse coups and social and military actions that culminated in the “Maria da Fonte” revolt and the Patuleia or Little Civil War of the 1840s. Throughout this period of conflict, which also witnessed the independence of Brazil, which had been the main sustenance of the Portuguese economy, Portugal became poorer and more radical in social terms, divided between a very conservative rural population influenced by the Church, which did not understand the Liberal ideals, and a small group of elite estrangeirados, who desired more advanced European models for the country. In between one and the other, the military – which took part in the Civil War caricatured by Daumier[6] as a tantrum between two brothers, one supported by France, the other by Austria – had gained substantial political importance that needed to be held in check, as a condition for lasting peace. This was without question the main positive achievement of the Regeneration, as it was able to put an end to a continued climate of guerrilla warfare, of which the “Remexido” exploits in Alentejo and the Algarve were the final outward sign.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 23-06-1881

MRBP.RES.2.3

Another achievement of the Regeneration movement was the public works policy, initially driven by Fontes Pereira de Melo, the most important politician in Portuguese monarchic liberalism. His Christian names, António Maria, were referenced by Bordalo as the title for one of his most important periodicals, parodying the developmental aspirations of the regime and many of its undeniable failures. However, the caricaturist knew, as did all Portuguese citizens of the day, what the country owed to that proud and pragmatic man who fought until his death in 1887 for an improvement in the country’s economic activities based on the parameters set by European modernity. “Fontism” was thus a kind of second name for Regeneration and was reflected in the opening of modern tarred roads that linked various regions of the country, the beautiful bridges over the Douro in Porto, designed by Gustave Eiffel and his associates, and, above all, the railway network he introduced to the bucolic landscapes, the greatest symbol of 19th century industrialisation.

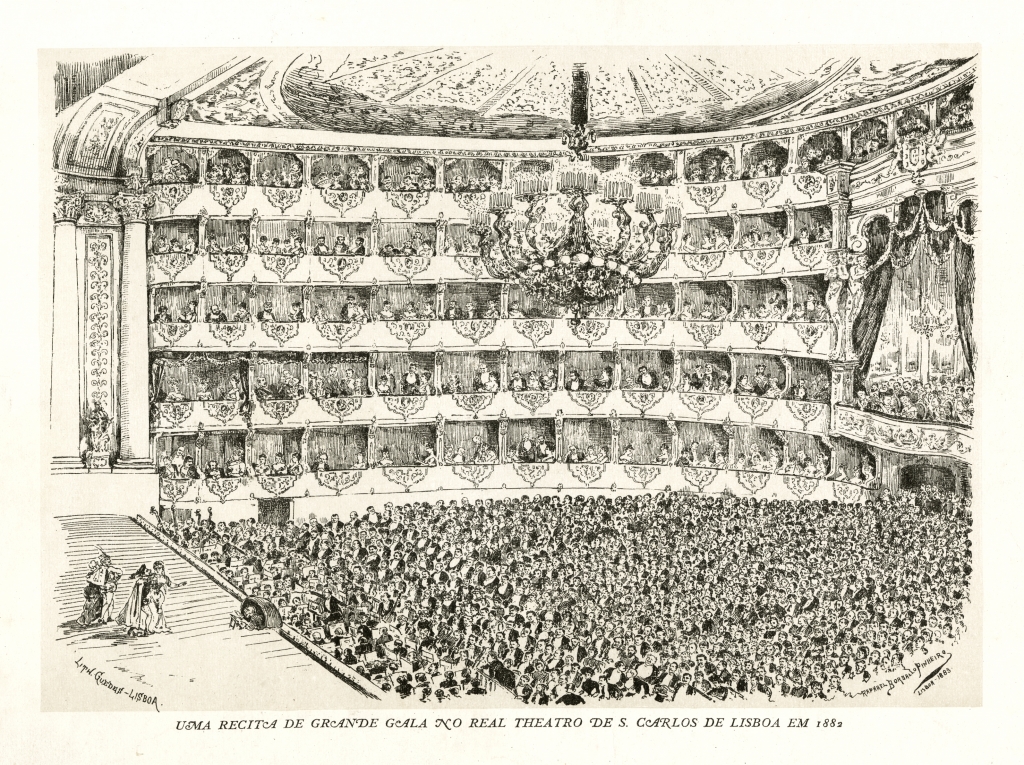

Etching

Caetano Alberto

O Occidente, 01.11.1882, p. 245

MRBP.RES. 8.5

These development infrastructures coincided with a continuous growth in the population, particularly in the major cities. Gradually they took on the values of the new civilisation, be it in the erection of public service buildings or in the laying of functional new avenues linking the railway stations and the historic city centres and with the modern public promenades where the ideals of bourgeois conviviality were perfected. The third aspect of the Regeneration worthy of highlight has to do with the intensity of the political life, whose representative stage was the parliament, between the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies. Despite the rather elitist nature of legislative representation – which required royal appointment in the case of the Peers, and an election based on the census and for male voters only in the case of the Deputies – this was one of the golden periods of Portuguese parliamentarism. One single example suffices to corroborate that assertion, that of Almeida Garrett, whose legislative output in the field of culture was of the maximum importance in the early stages of the new regime, between the “Septemberism” of 1836 and the Regeneration of 1851.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

A Paródia – Comédia Portugueza, 04.02.1903

MRBP.RES.1.4

Whilst it is patently true that very few MPs were of the calibre of Garrett and other Portuguese intellectuals, a look at the Diário das Cortes legal gazette revealed a consolidated and sophisticated political culture with a taste for democratic confrontation – proof that freedom of expression was an important achievement of that regime.

The attributes of Portuguese political life in the latter half of the 19th century, as well as the development initiatives of successive governments, supported by committed constitutional monarchs such as Pedro and Luís, and even Carlos – who was to represent the end of the monarchy – allowed for considerable modernisation of the country within the parameters of European capitalist economies. Nevertheless, Portugal was unable to match the dynamics of richer countries and, beyond the main cities, there remained considerable swathes of the country where pre-capitalist economics, reflected in traditional subsistence farming, remained in place. But there was always ambition on the part of the country’s governing politicians, who achieved success in certain fields, particularly in colonial policies, which were fundamental for supplementing the country’s weak internal resources. Here one can highlight the exceptionally good relations with Brazil, which was still attracting thousands of Portuguese emigrants and defined its own national identity on the basis of its linguistic, historical and cultural heritage from Portugal, as mentioned at the beginning of this text. One should also not forget the successful delimitation of the Angolan and Mozambican borders in an international climate of confrontation between the imperialist powers, as well as the systematic occupation of those vast and prosperous territories.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in A Paródia, 30.07.1902

MRBP.GRA.1053

The Portuguese intellectual and artistic elites of the late 19th century reflected, in the splendour of their best works, the positive achievements of the Regeneration, which fostered education and technical and scientific investigation, combated illiteracy and created the conditions for improved international contacts. Eça do Queirós recognised this when he evoked the young Coimbra students of the 1860s whose books that shaped the desire for modernity were delivered by train. That rebellious youth, one of the most brilliant generations in Portuguese history in the fields of literature, history, journalism, arts and ethnology, became fierce critics of the weakness of the regime in the 1870s when they began their professional careers. In particular, they blamed the regime for the accumulated delays in development in all areas.

Chromolithograph

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

A Paródia, 25-06-1902

MRBP.RES.1.3

The criticism was justified, but the variety and inventiveness of the way it which it was formulated revealed the civic, ethical and artistic quality of the so-called 70s Generation, which, paradoxically, provided testament to virtues of the system that educated them, allowing them to fully realise themselves. On the other hand, figures such as Eça de Queirós, Oliveira Martins, Antero de Quental and Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro were responsible for what was a kind of atavistic addiction to the historical negativity of the country in relation to itself, which Eduardo Lourenço analysed brilliantly one hundred years later in his classic book O Labirinto da Saudade [The Labyrinth of Saudade]. Psicanálise mítica do destino português [Mythical Psychoanalysis of the Portuguese Destiny].

Eça de Queiroz, Carlos Mayer, Guerra Junqueiro, Ramalho Ortigão, Oliveira Martins, Carlos Lobo d’Ávila, the Count of Sabogosa, the Count of Arnoso, the Marquess of Soveral and the Count of Ficalho.

Photograph Proof, b/w

Ca. 1887-1893

MRBP.FOT.774

The estrangeirados, who regarded Paris as their cultural capital, and many Portuguese intellectuals of the period presented Portugal as an enigma: backward, corrupt, lazy and incapable but at the same time intense and authentic in its rural cultures whose extremely rich heritage – both material and intangible – had begun to be studied and catalogued. This paradoxical attitude was brilliantly portrayed by Eça de Queirós in his final novel, The City and the Mountains, in which the urban, Parisian civilisation, overcome with the emotions of memory, succumbs to the values of a paradisiacal world derived from this pre-industrial backwardness.

Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, a Lion Group Artist

The Portuguese visual arts of the period did not reach the importance of the literary output. Nevertheless, they elaborated a mythical image of Portugal that must be included in the history of the country’s culture, even today.

To put it very simply, one could say that the paradoxical way in which Eça de Queirós viewed Portugal, somewhere between sarcasm and sentimentalism, was represented by the naturalist painters in the form of a strict homage to sentimentalism.

Predominantly landscape painters, artists such as António Silva Porto and João Marques de Oliveira – who were able to train in Paris and Italy in the early 1870s thanks to state scholarships – and their many disciples depicted the very essence of the motherland: the beauty and variety of the landscapes; the intensity of the farming life or coastal fishing activities, based on traditional techniques where machines were not welcome; the down-to-earth simplicity of an anti-urban people whose values where defined by tradition and heritage.

Working for an urban bourgeois market, whose capacity and taste for investment in artworks was always relative, the Portuguese naturalists did not distinguish themselves through formal or aesthetic confrontation. They also followed the new trends from Paris at a great, safe distance. They enthusiastically adhered to the code of the Barbizon School, crystallizing, with very little variation, in their cult of plein air painting, devoted to capturing the changing light and colours at different times of the day and in the passing of the seasons. But they paid little attention to the formal consequences of painting the variability of what was seen, as the Impressionists did, or to the criticism of their restricted materiality, as executed by the Symbolists. Despite their lack of passion – if we think in terms of the aesthetic vanguardism with which I characterised the idea of modernity at the beginning of this text – Naturalist painting was a dynamic field that produced the popular scenes of José Malhoa’s work as well as the ephemeral and provocative work of Henrique Pousão. If one were to use a literary comparison, one could associate the former with the narrative sentimentalism of Júlio Dinis, and the latter with the modernity announced by Cesário Verde.

Oil on canvas

Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro

1885

Museu do Chiado

In Lisbon, the Naturalists were, for the nascent critics, above all the painters of the Lion Group, who feature in a group portrait of 1885 by Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro. The group was named after the restaurant Leão de Ouro where it met, in what is now Rua Primeiro de Dezembro. A very noteworthy work, it shows the peculiar talent of Columbano, who shunned the plein air aesthetic of the landscape painters but wanted to capture the importance of the painters of his generation grouped around Silva Porto, giving more prominence to the latter’s direct disciples (João Vaz and António Ramalho, who flank him) and the sleepy figure of José Malhoa. He portrayed himself as being about to exit the scene, wearing a top hat and with a cane under his arm, playing ironically with the heavier-set figure of his brother Rafael, who is sitting at the table looking out at the future observer with a sympathetic air.

In the final two decades of the century, Rafael made sure to make a fraternal reference in his publications to the Lion Group exhibitions which were replaced by the exhibitions of the Artists Association in the 1890s and those of the National Society for the Fine Arts from 1900 onwards. He thus contributed, as did other newspapers and magazines, to the consecration of this generation of artists that created and nourished a stable market with their painting inspired by the international technical and iconographic innovations of the mid-19th century. As the years passed, their always relative modernity diminished even further, but Rafael revealed no critical attitude in relation to their conservatism. Indeed, it fit well with his understanding of Portuguese life and culture and the possibilities of the country asserting itself internationally.

But in relation to those artists he was friends with and promoted – and even in relation to his brother Columbano, without question one of the most important Portuguese painters of the century who, still today, is worthy of international recognition – Rafael occupies a unique place that is worthy of elucidating further. When discussing the personality of the caricaturist in the indispensable European context, I argued above that one of the specific inherent characteristics was the sceptical optimism with which he passionately experienced his time. Without any longing for past history, he understood that progress was a condition for the development of a nation. But he also believed that the profound transformations he advocated should not eradicate any anthropological traditions or national peculiarities, and much less the organic rhythms of life, where work was not necessarily the be all and end all. As a Bohemian, Bordalo could not imagine his daily life without the leisure, the long nights, the time spent in pleasant conversation, in little restaurants and, above all, in the theatres.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro Lisboa 1883”

MRBP.GRA.32

He loved, first and foremost, freedom of existence and, at the same time, the supreme liberty to analyse and criticise the governments and society of which he was a part. Indeed, he often included himself in his caricatures, just as he often felt co-responsible for civic victories and defeats.

But Rafael’s unique and very high place in Portuguese cultural output of the late 19th century is anchored in the positive way he married his tastes for civic intervention with his artistic vocation. A compulsive drawer, who viewed the world via the outlines of its permanent representation, he also cultivated, with the same urgency, the arts of speech and writing. As a performing artist who originally wanted to be an actor, it was natural that he would choose an art form that had an immediate impact, fed by the events around him and giving rise to their own. A man of the salons and urban pleasures, he needed to make art surrounded by people, immersing his whole body and merging inspiration with execution.

He could, therefore, only be a journalist and caricaturist. They were fields that had an importance then they no longer have today. Rafael did not illustrate other people’s publications, nor did he produce his caricatures on commission. Assuming, without the slightest problem, his genius and choices, and proud and adventurous, he almost exclusively worked for newspapers and magazines he entirely owned – in terms of conception, the naming, and the choice of collaborators, no matter how important they were. Ramalho Ortigão and Fialho de Almeida, for example, always recognised him as a boss who was demanding, inventive and a friend.

A satirical virtuoso close to the brilliance of Daumier, Rafael may not have had the latter’s formal modernity, but in terms of the civic commitment they both applied to journalism, he was by no means behind Daumier. And he even overtakes him when one thinks of the fierceness with which he defended his work, which was always threatened by financial conditions and, frequently, by political (above all, censorial) developments. The unique place I would claim for Bordalo derives essentially from the modern, at times revolutionary, understanding of his art. He was not interested in the glory and regarded art, somewhat romantically, as the instrument it was – an expression of the self but also of society and its issues and causes. A socialist without party affiliation, he set his hopes on the republic. And as he rejected social hierarchies, his commitment in life, work and art was always to the people. To whom he remained close as he did with the workers at the printers and the craftsmen at the Caldas da Rainha factory. To what was far from him, and for which he created a name, the figure and tales of Zé Povinho, which he coincided with his idea of the motherland.

Lithograph

Signed “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Pontos nos ii, 18-03-1886

MRBP.RES.3.2

A man of the Arts and Crafts movement, his desire was to unite art and industry through his artistic talent for drawing, writing and design, but also by means of old, traditional crafts and a popular culture more anthropological than historical. Unlike so many of the intellectuals, politicians and writers of his generation, he was never a defeatist, nor did he ever think that Portugal’s backwardness, or the political incapacity to put an end to it, was reason enough to do nothing but complain or give up. What he always wanted was that Zé Povinho, the people, would stop bowing to the powerful and wake up out of their indolent and acquiescent slumber. Holding the mirror up to himself, as a warning against his own capitulation, in hundreds of drawings, Rafael drew Portugal of the Regeneration period with such acuteness and inventiveness that today we still recognise ourselves in his exaggerated drawings that also constitute the first cartoons of modern Portuguese culture.

Photograph Proof, b/w

undated

MRBP.FOT.476