A Thorn in the Side

By João Paulo Cotrim

It’s a risk. In a multifaceted oeuvre, whose brilliance is multiplied at every reading, but still retains corners of shadow, to choose a strong image, a detail from an enormous fresco, minutiae from the great production, is to open the door to the labyrinth.

Beginning at the beginnings, which are many, would be appropriate for emphasising a timeline: the first album of caricatures, the birth of the metaphor for the country, the definitive introduction of the graphic narrative, the application of colour to printing, the founding of periodicals, the unfettered use of autobiography, the social impact, and so forth, in all directions. But boring because it is so restrictive, a procedure that reeks of autopsy.

To begin with the magnificent “Twenty years after” puts us at the way out straight away. Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905) assessed himself in two poses linked by the vaulted ceiling of time. From the dandy with the bowler hat who responds haughtily to a humble request from the bent old man in the top hat it is only a cat’s leap, from the rooftops to the quiet comfort, from O António Maria to A Paródia, pages falling out of his pockets in a form of calculated negligence. The artist asks himself for a light, at the end of a life given over to the flames. A sign of total dedication to art, Bordalo’s life cannot be separated from his work. This approach would take us far, but the symbolic load is too tempting, perfect in its completeness.

The same applies to another possible opening, taken from the pages of the Álbum das Glórias: the full-body figure of Zé Povinho, his ceremonious donkey saddle nearby, wearing the colours of passivity and hope, with Ramalho Ortigão/João Ribaixo writing the accompanying text, like the guitar accompanying the voice in a fado performance. That is his most popular, most perennial, most debated figure. Involved in so many adventures and mishaps, a victim and anti-hero, country and individual, he could serve as a chaperone in a review of the printed work of a drawer the authorities taxed as a portraitist. But his weariness prevents him from accompanying us on our vertiginous journey, though we shall not exclude him from our selection, which we want to be imperfect and narrative.

So, curtains up on the private exhibition. The mechanism is always in scene, one only has to unfold the eight pages of Os Pontos nos ii of 18 June 1885. Under the title “How it grows…” it immediately features, on a framed page, Zé Povinho making his affliction known, his arms hanging in a dynamic that accentuates his goggle-eyed look, his tongue out. Stuck to his throat, he carries Fontes Pereira de Melo wearing a crown, who, as it is on an uneven page, comes with the surprise of seeing the crown, a symbol of power and ambition, grow beyond the three following double pages, and another last page. It begins by superimposing itself on the text of the chronicle of the week. Maria da Paciência, the publication’s mascot, observes from atop one of the columns, while little figures use the borders to walk around on or to climb. In one corner, a fly has been caught in a web. The crown then rips the typical Saint Anthony image, invoking the image in which we see, for the first time , Zé Povinho in bewilderment at the revered saint… Maria, with the baby King Luís on her lap, both of them protected by the hat from the raindrops, authentic “pointed knives”. On the steps of the throne/altar we see the shirt bibs, all shiny from too much starch, an allusion to the civil governor, Peito de Carvalho [peito meaning breast or chest in Portuguese]. Nearby, dancing at local feasts, despite the bad weather, are a number of top-hat wearers, perhaps even Rafael and Eça, while others take advantage of the corners. The Marquess of Valada, for example, with “flowing hair” and “fingers curving in serpentine tension” struggles to climb upwards. On the bottom border hangs a guitar on one side and a tooth on the other. As a footnote, the verses of Pan-Tarântula, aka Alfredo Morais Pinto, Bordalo’s literary collaborator at the time, set the tone for the scene. And it goes on for three more pages, the text returning in running text form, once again scattered with figures, some wearing dark glasses due to the shine from the starched bib which also hangs over the text as a “bastion of the state institutions”. The lower half provides space for caricatures that throw light on the week under review, mixing theatre, parties, the zoological garden and politics. The borders grow closer together to form a cage for a parrot that has escaped from one of the plays that is a “vulgar reproduction of what has been going on in parliament for many years”, or to receive the nests of other birds that do not refrain from defecating. This close to the “(end of the crown)” when illustrious bearers, one of them the commander of the municipal police, carry the altar/throne. Just like that other “disorderly republican” who the Bohemian route leads along the Rua do Príncipe, next to the Duke’s Palace after an evening at the theatre in Príncipe Real, the artist himself dives into murky waters for having gone to Caldas… da Rainha.

Despite the fact that, at this time, his attention was disputed by pottery and its respective capital, we are witnessing the Bordalian feuilleton in all its glory – disperse but unitary, basic but complex, served by a style consisting of outline and shadow, mature in composition, rapid in response. The principle characters – the emblematic Zé and historic Fontes – emerged in expressive portraits, accompanied by “extras” in miniature form but still bearing recognisable faces from the political scene of the day. Each one, if their importance justified it, had a specific feature that became their identity, such as the crown that is part of Fontes’s body, or the prominent starched bib of Peito de Carvalho. Many times the idea was a simple one derived from the gossip from the salons that created empathy and gave rise to reactions. The main caricature launched a story told in text and images that went beyond the limits of the page, introducing time into the act of turning the page – suggesting movement while it established organic relationships with the word, with the other drawings and with the whole. Never failing to implicate himself with self-irony, the artist used a particular moment in the life of the city to raise more far-reaching issues. By means of such a mundane agenda, the pace of daily life and every theatre performance, he addressed issues relating to politics, the regime and, last but not least, power.

Hunter of Types

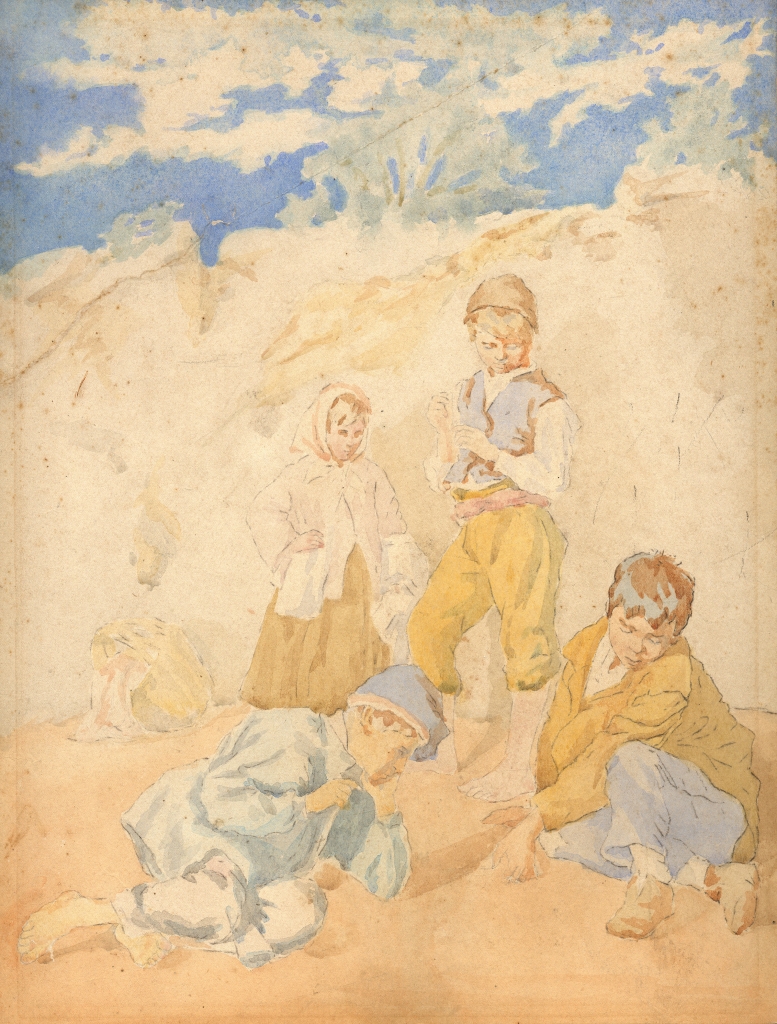

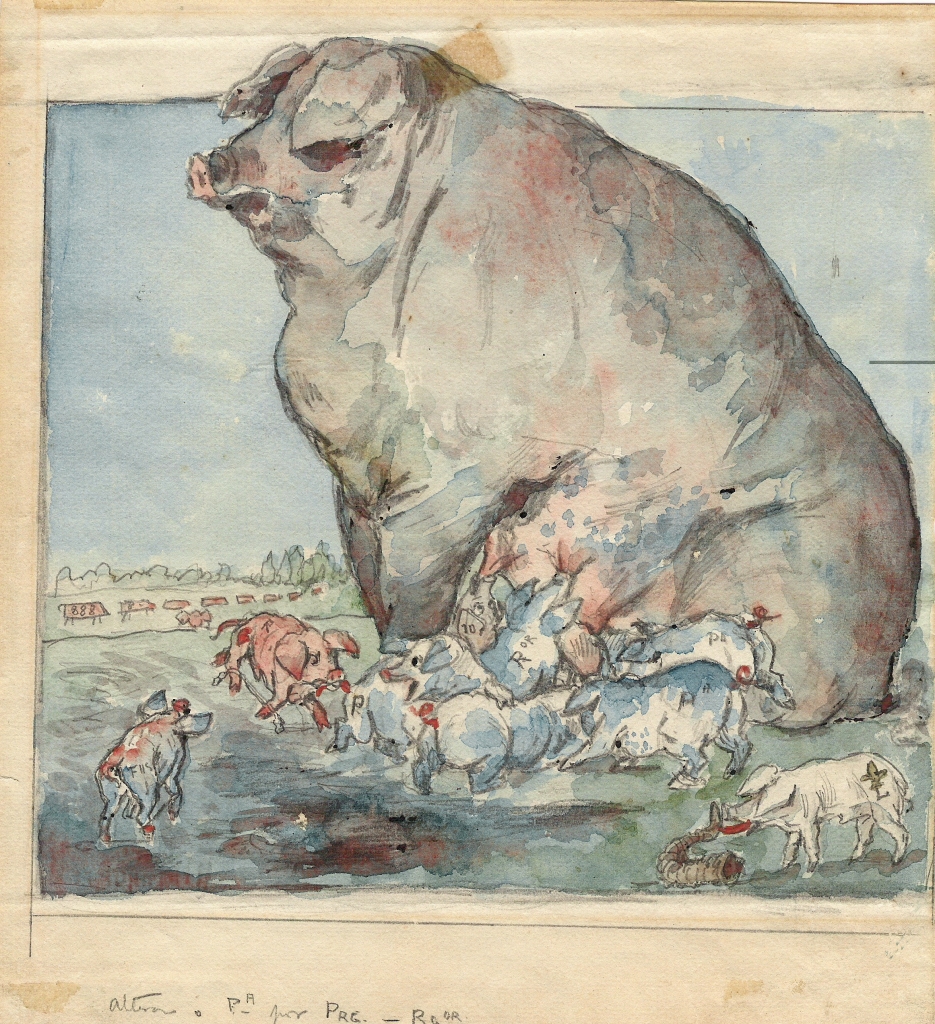

Watercolour drawing on paper

unsigned/undated

MRBP.DES.1199

It is no wonder that it was characters that awoke Bordalo’s vocation. Did they not occupy a central place in two of the young Bordalo’s passions: theatre and bohemian life? After having experienced the theatres and nightlife, while his inclination continued to live in him, the time finally seems to have come for him to settle down in the happiness of marriage. His talent pushed him towards a career in painting, and his dedication and commitment to the natural drawing was noted. His attention to his surroundings and to the tastes of the day were successfully reflected in Village Wedding and a number of watercolours on types and customs that were exhibited, and continued to be for several more years, to good critical reception.

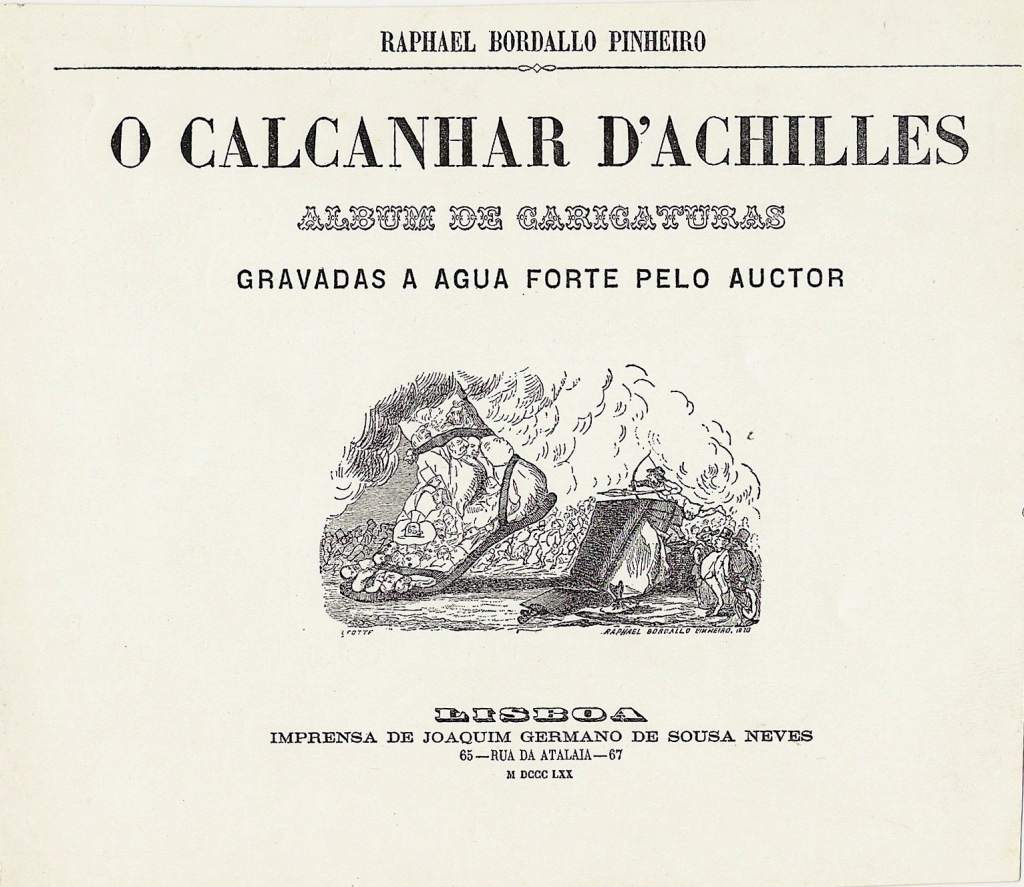

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro 1870”

MRBP.GRA.1162

But the periodical for the politically motivated and militant youth, Revolução de Setembro, in its issue of 31 August 1869, published four anonymous sonnets dedicated to four literary figures, the playwright, such as Luís de Campos, “representing the horror of the good husband/and scourge of all jealous husbands”; the writer and polemicist, such as Ramalho Ortigão, “a type like him is always a hero”, given that he “knows things that confuse the wise/and he learned in Paris just about all – who turns a feuilleton into a knife!”; the chronicler, such as Manuel Roussado, “here is a type of wit and cuisine/with tasteful sayings”; or the sensitive poet Eduardo Vidal, “a delicate flower! crying only/sighs that come from some misfortune”. Bordalo could not resist illustrating them and showing the works in the bellybutton of the world: the cafés and editor’s offices of Chiado. The success was such that the author, Clemente dos Santos, the future Micromegas from the pages of A Berlinda, had to reveal himself as such. This encounter led to the project for an album that would reveal “the vulnerability or grotesque aspect of each individual caricatured”

Etching

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro 1870”

MRBP.GRA.987

O Calcanhar de Aquiles, which was launched immediately after publication of a single sheet , in 1870, but was not sold out.

Etching

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro 1870”

MRBP.GRA.984

On the cover, a foot made up of human figures and wearing a sandal takes a step. Pointing at the heel, ready to launch the arrow, is the young Rafael with a bow and quill of a draughtsman. There are people who stop to watch and others who run away. The content was a deferential and duly authorised series of caricatures of faces from the literary and arts world in mildly satirical situations: in addition to the four mentioned above, for example, we see Herculano swapping the academy for exile in the country, provoking him. The artist introduced himself to society thus, his language of choice already sketched out for him. But he lacked a programme, which was to be announced months later with the first newspaper to be sold in the theatres and the initial experience of publishing periodicals.

Lithograph

Signed: “October 1870 Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

Published in O Binóculo on 29.10.1870

MRBP.GRA.1132

“O Binóculo presents, it does not comment. It analyses, does not summarise. It shows types. And our century is one of types. Archetypes or prototypes, it does not matter. The type is of the greatest importance today; our century only admires types. (…) Binóculo is impartial because it is for all. With the same strength. With the same intention. To vulgarise, correct without offence, punish without malice.” This way of doing things was to become a constant practice. Bordalo’s approach was one of bonhomie, despite the occasional outburst of aggression, despite the combats and the polemics.

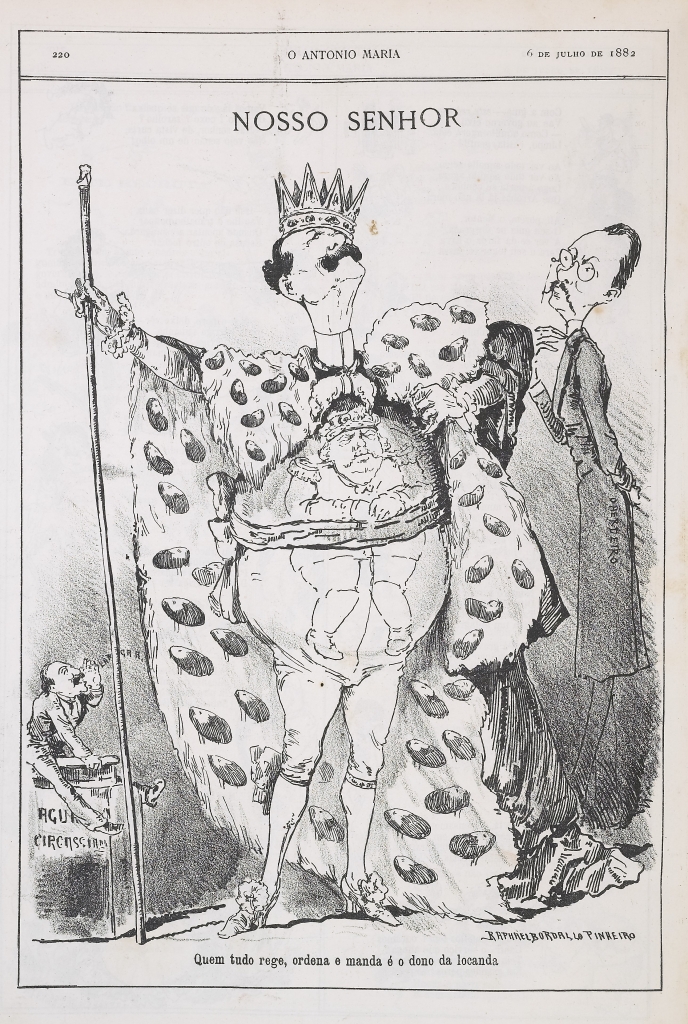

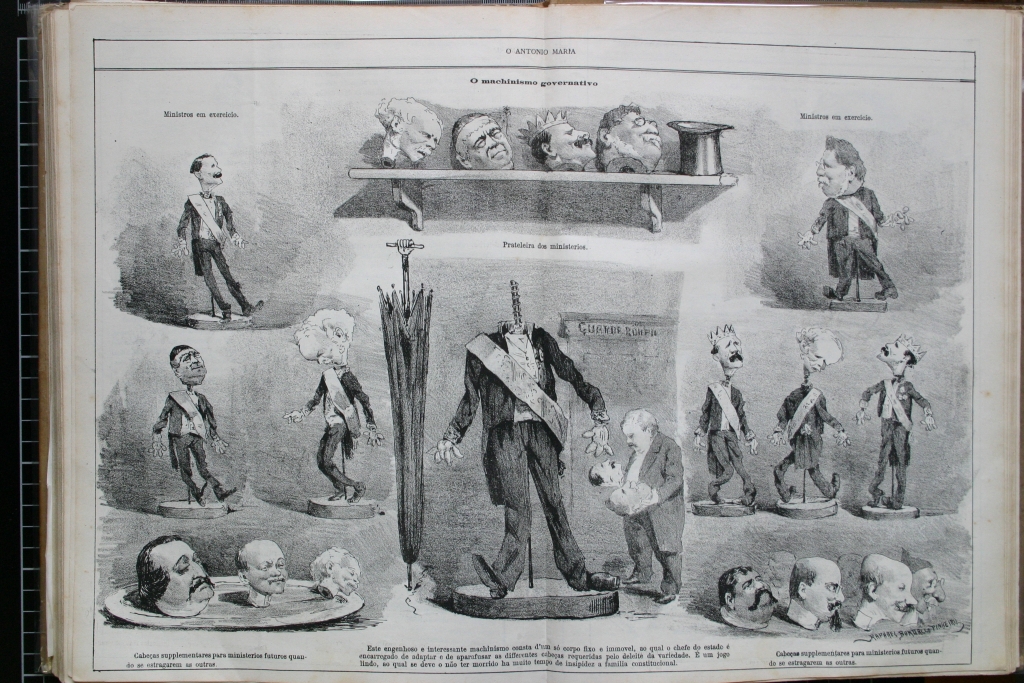

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 06.07.1882, p. 220

MRBP. Res. 2.4

Fontes, “Our Lord”, who sees himself as God’s gift , the target amongst all types, eternal representative of power, and enemy number one, was to be eulogised at the time of his death, as one of his great companions . Binóculo’s charter of intentions showed its aim of observing from a distance, but it did not yet define a horizon.

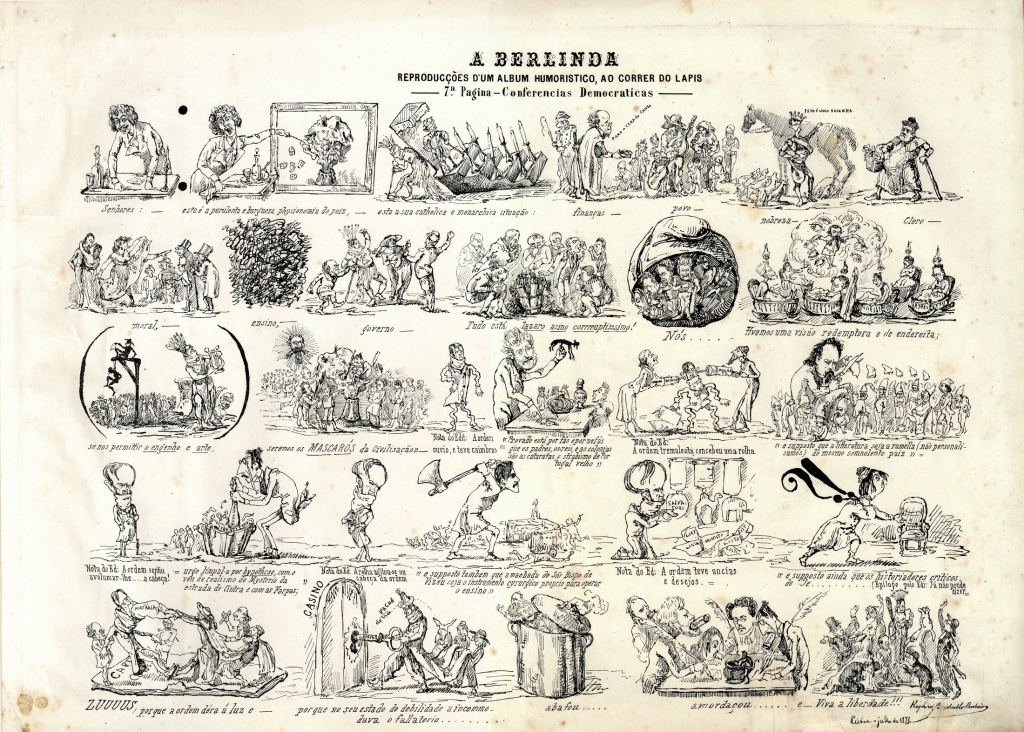

This periodical, dedicated to the theatre world, had interrupted a sequence already begun, in the seminal year of 1870, with the first three pages of “a humoristic album, straight from the pencil”: A Berlinda. Benefitting from the new winds that in the heart of Europe revolutionised the old tradition of storytelling with images into a new form of narrative, while at the same time caricature was becoming the voice and vision of political journalism, Rafael Bordalo established in Portugal what, many years later, was to become known as the comic strip . The first six sheets, which were sold loose with relative success , made political comments on current affairs, including the coup of 19 July, the situation in Europe, using a map that was pioneering in its use of colour, and then returning to domestic politics on the following pages, including the Carnival (which was to become indispensable in the Bordalian lexicon), until the seventh sheet was published, a report/commentary on the banning of the famous Casino Conferences. “Ladies and Gentlemen”, Bordalo himself in self-portait proclaims, “this is the purulent and bourgeois physiognomy of the country”: the Catholic and monarchic situation of a fallen throne/altar; the tax authorities that rob while pretending to beg from a people in misery; a nobility whose horse is a shadow; a pot-bellied, well-fed clerus; dissolute and adulterous morals; education that is a stain on society; a government in party mode; all in all, “everything is leprous, stupid, corrupt”. In other words, rotten and stinking. He contrasted this with the intellectuals – Antero, Eça, Batalha Reis, amongst others – an approach with comprehensive, long-term vision. Except that the order trembled until it came up with a way of putting a stop in that: the ministerial order that closed the casino and silenced and muzzled the congress attendants. In the end, the bourgeois and catholic order celebrated. At the bottom we see a written chant: “Long live Liberty!!!”.

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro Lisbon July 1871”

Published in A Berlinda, 1871

MRBP.GRA.1553

The artist who joined that group brought with him a vocation, served by the means of caricature, and an audience. He now assumed his own programme, touched by the utopian perfume of the Commune: to civilise the nation by making it see its Achilles heel. Whilst wearing a monocle.

Etching

unsigned/undated

Published in The Illustrated London News, 26.04.1873, p. 392

MRBP.PP. 307.62

The Wild Garden

Gripped by the fever of telling it like it is and making others see, the following years were little less than hallucinating for Bordalo. The organism that fed off current affairs and everyday life, theatre and politics was to grow like ivy, and turn into a leafy tree that was to burst in a garden, a park that hides and reveals the details of an intimate theatre, that of the gardener and hunter. He contributed to almanacs and newspapers, some of them Spanish and British , spreading his drawings through countless books, something that he would always continue to do, out of friendship or for budgetary reasons, with irregular quality, revealing only breaks in one or other cover, in strict obedience with the tastes of the period.

Watercolour/etching

Signed: “RBordallo Pinheiro”

Published in El Mundo Cómico, 19.07.1874

MRBP.GRA.947

Rafael Bordalo was not only to be found on the central avenue that was his main projects. Side streets and more remote squares were to emerge following no other discipline than the taste of the occasion, in solidarity or, to varying degrees, cultural celebration campaigns, proposing advertising to sustain his publications, drawing faces on solemn menus, reflecting the period of banquets he lived in, or adding images to the musical note sheets used by the bourgeois in their family soirées and, of course, drawing figures for ceramics pieces. Later, thanks to political opinion one-off editions containing advertising and, once again, tribute publications were to spring up like mushrooms. To this one can add autograph albums, a common practice in the houses and within the friendships of the day, as well as correspondence.

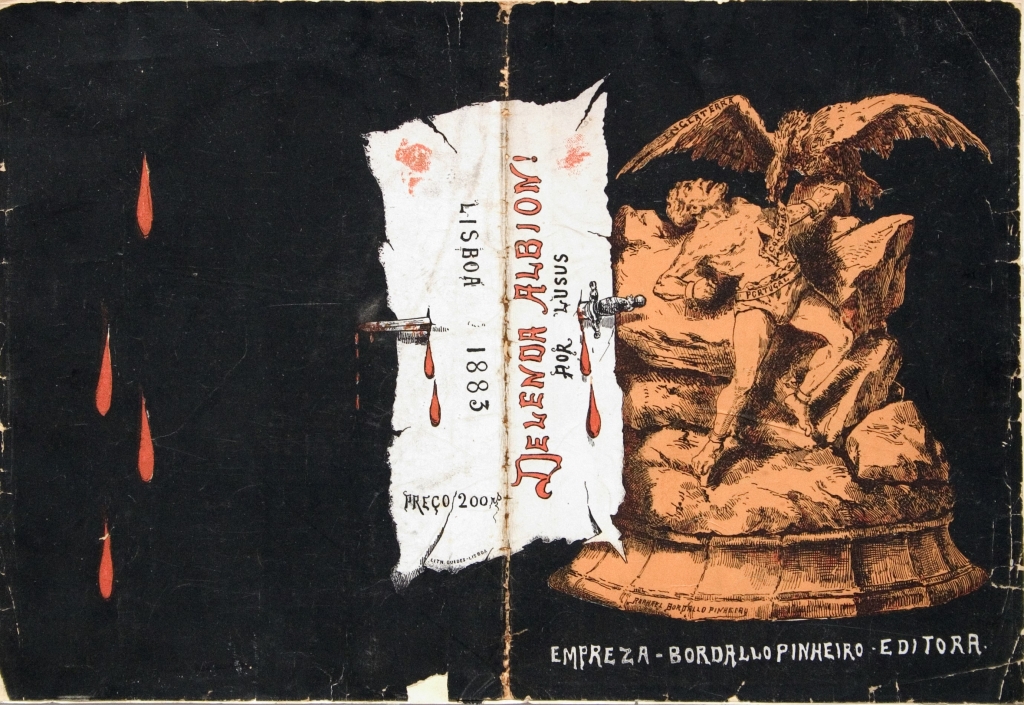

Chromolithograph

Signed: “Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro”

1883

MRBP.GRA.28

Epistolography was an important adventure that ran through life and work, or to put it more precisely, became a wandering terrain for correspondence between the two. In addition to the intimacies, emotions and playfulness exchanged, they were also the perfect example of the integration of text and image reflecting the absolute desire to tell a story with the artist inside. In A Lanterna Mágica, the second attempt at the periodical, a “useful information” page explained why we see the artist’s “detestable calligraphy”. A typesetting machine teamed up with the delivery men on strike, landing it in prison, from where it was released on bail only to once again flee when heading for legal proceedings. Later, in Brazil, in O Mosquito , Mr. Bordalo Pinheiro experienced a “serious disorder” that prevented him from meeting his obligations. The centrefold pages, which sometimes competed with the covers of periodicals in terms of importance, was filled with the excuses of publishers on top of a missive that explained, in text interrupted by images, that illness obliged him to swap the “throbbing issues” of the day for a period of convalescence. A serious, and very much unique, case was the series of open letters between him and the Brazilian caricaturist, Ângelo Agostini , which began in Psit! and continued on to O Besouro, giving rise to O Besouro de Chicote and a post-scriptum in which a bootlicking Agostini is kicked off the page, a graphic gesture that he was use to use again, with people being pushed off the edge into the abyss that was the fold. What had begun as a tribute from his colleague from the Revista Illustrada on the emergence of Psit!!, albeit sarcastically referring to the fact that Bordalo had become an importer of Portuguese sausage, veered off into an argument on the creative freedom of each one, with a crescendo of insults. He was never to experience again such violent indignation, which was to produce intense pages full of creativity, in addition to valuable insight into the social role of the caricaturist. Twenty years later it was forgotten . Some of those depicted were lucky enough to be so more than once. His Majesty the King was a common subject, be it at the end of No Lazareto de Lisboa , ironically asking for the commendation awarded to the emigrants in the Lands of Santa Cruz [Brazil], or in O António Maria extending his gratitude, with no less irony, for compliance with the request for a new haircut.

Another type of “charter” was to emerge years later in Paródia-Comédia Portuguesa , as a result of a printer strike: a handwritten publication, like those in schools, “full of ideas, full of facts, anecdotes and ink blots”. Once again, the integration of diverse elements while concentrating on the whole designed a narrative that was directed at the audience personally. Yes, the periodicals, with their opening and closing editorials, information on subscription, the feedback on the reactions to them, but also the pure commentary, the caricatures where the artist winks at the reader, the cartoons where he speaks of his troubles or anxieties, plus the loose albums – is it really too much to expect, i.e. to read the whole body work repeatedly addressed to us like a long and fragmented letter?

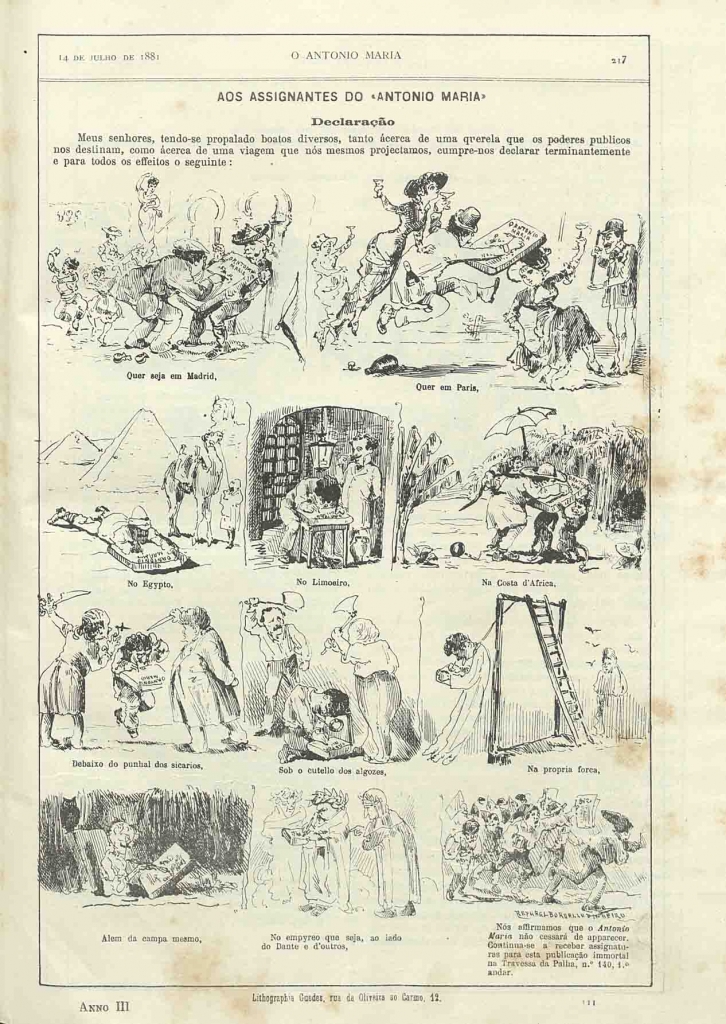

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 14.07.1881, p. 217

MRBP.RES. 2.3

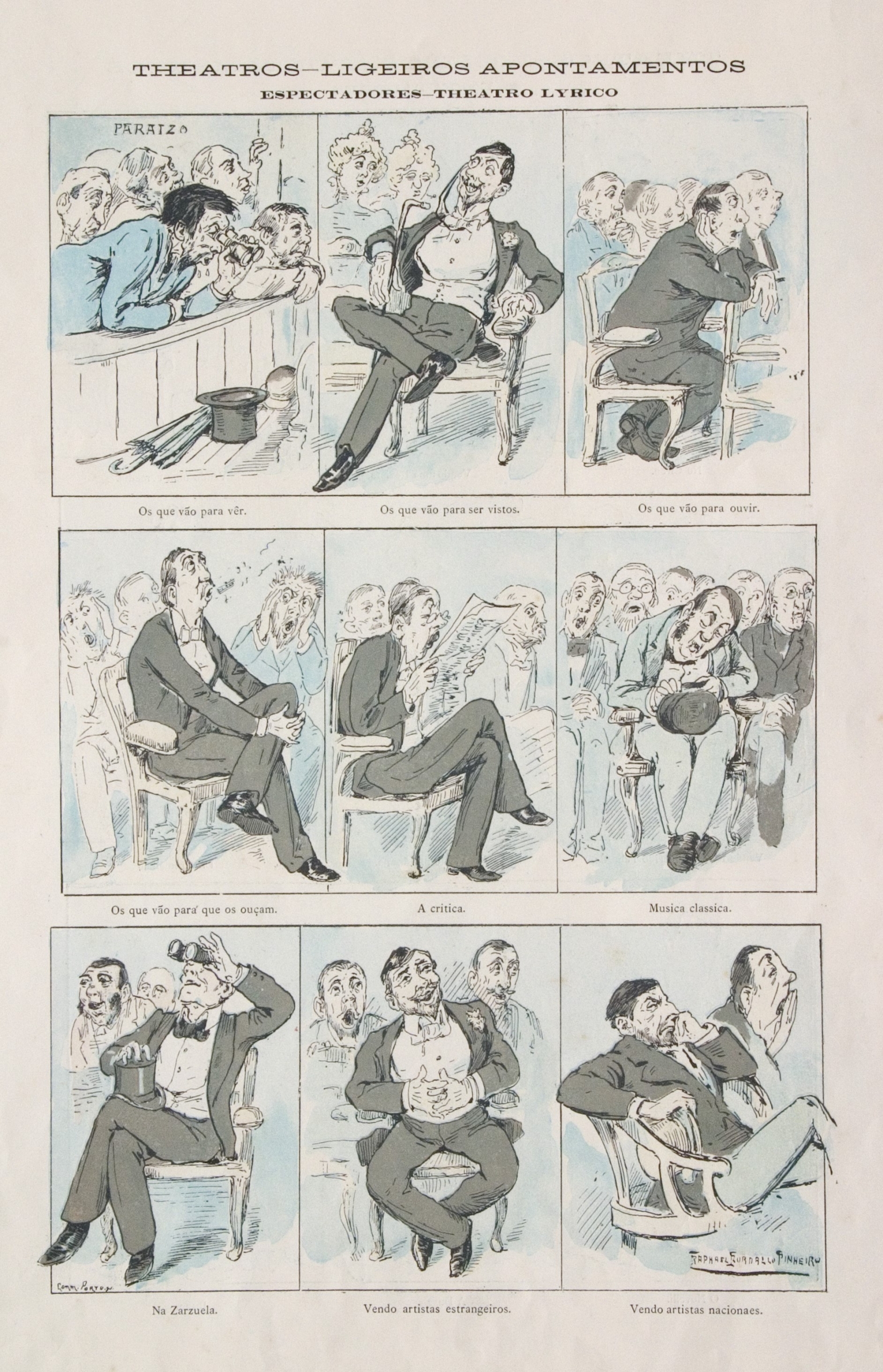

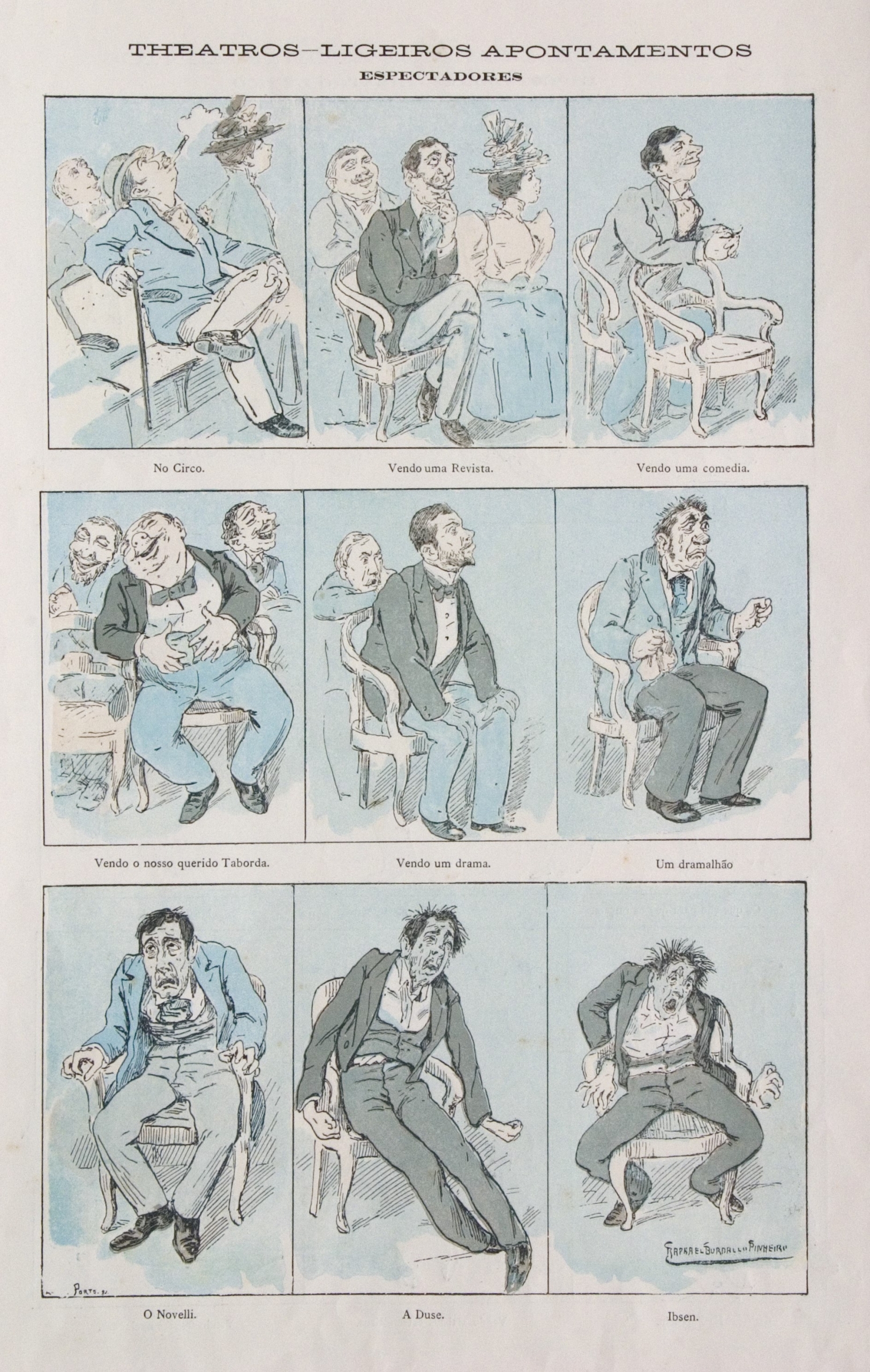

Stage, the Corpus of the Actor

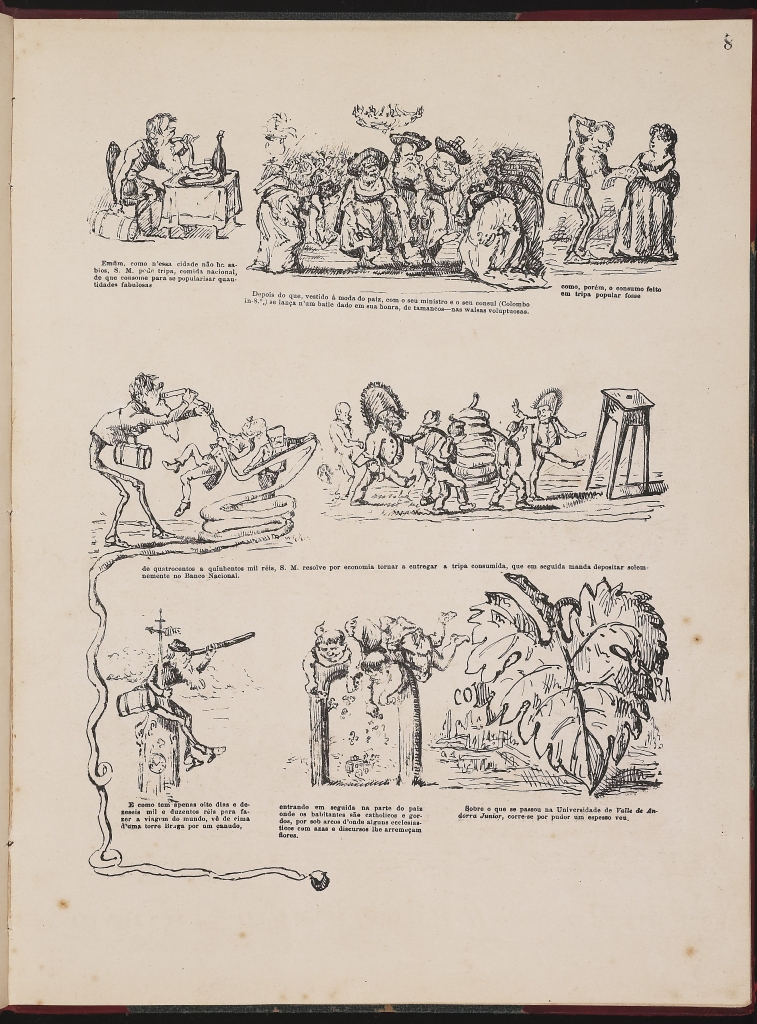

The fertile land for such a feuilleton could only be found in the pages of the periodicals, as indeed had been the case in Europe for decades and became the norm in Portugal as an extension, on paper, of the salons, where the “topics of the day” were discussed well into the night in the sacrosanct Lisbon triangle between São Bento, São Martinho and São Carlos. Until reaching the glorious heights of O António Maria, the gardener was to sow some seeds – for flesh-eating and hothouse plants. He produced three cartoon albums in the strict sense of the word. Notes by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro on the Picturesque Travels of the Emperor of Razilb in Europe (1872), which dealt, in its most spontaneous aspect, with the en vogue topic of travel, here applied to the cultural sites of Europe and an illustrious ruler and lover of the arts: Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil. Wearing slippers and with a huge trunk, one sees the emperor in fourteen strips, including a stop in Vale de Andorra Júnior, i.e. Portugal, for feasts, visits to the academies in Lisbon and Porto and even a meeting with Alexandre Herculano. Before the reader’s eyes, text and image together perform a vertiginous dance of creativity in the service of storytelling, with the words vibrant in their effort to follow loose drawings full of minute details that change in style, disrespect vignettes and sizes, invent iconic symbols, or condense or extend the time of the narrative, all reflecting the most modern tastes and know-how. There were three editions of this first cartoon album on Vale de Andorra Júnior.

Lithograph

unsigned

Annotations by Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro on the Picturesque Travels

of the Emperor of Razilb in Europe, 1872, p. 8

MRBP.RES. 51

M.J. ou a História Tétrica de uma Empresa Lírica, a year later, provides insight to a season at the São Carlos opera house, which seemed to have as much to do with lyrical theatre as football does today. Bordalo once again portrayed himself in the role of commentator/supervisor.

As we have seen, the figurative narrative formula was to be used again and again, reflecting the complete and complex array of the relationships between the images, and between the image and the text, and the relational dynamics as a whole. His trip to Brazil is related in O Mosquito and his return gave rise to a short book that anticipated one of the contemporary literary trends – the autobiography. In the Lazareto de Lisboa is a four-part report on the journey and his quarantine before being able to re-enter the imperial capital. The nostalgic “Souvenirs”, with the Sugar Loaf Mountain unable to hold back a tear at the farewell, is followed by a brief description of the trip which ends in the topic referenced in the title: his inability to caress the motherland, represented by a Tower of Belém-cum-countrywoman with headscarf holding out her arms, because of the compulsory quarantine period “in the Lazaret”, a place of dubious utility and hygiene installed in the Tower of São Sebastião da Caparica on the south bank of the Tagus to which he would return some years later . For the responsible minister of the kingdom, Bordalo was an “emissary of the Black Vomit”.

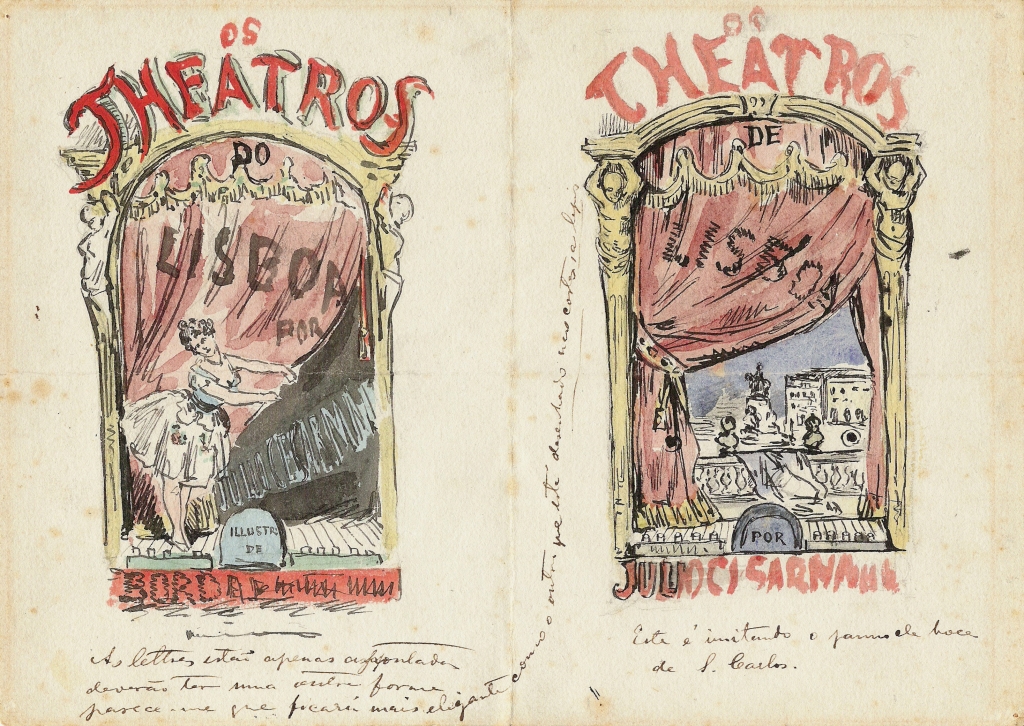

Before his formative sojourn in Brazil Bordalo had left an album of caricatures, the very curious fruit of his collaboration with Júlio César Machado. Album of Caricatures – Sayings and Maxims in Portuguese is a collection of 13 prints illustrating Portuguese proverbs and popular sayings in street scenes on sheets, in large book form and on sheets of paper, and small stages, that cause reactions in specific normal types – be they fado singers, newspaper sellers, dandies and old women with headscarves, dogs cats and mice and also urchins… Vernacular speech (“cracking a joke”) and wisdom of the street (“there is no better mirror than an old friend”) are reflected in the images. The essential character of the volume lies in Machado’s notable text. Machado was an intimate witness like no other to Bordalo’s youth. Both spent their time exploring – inside and out, in the audiences and in the wings – The Theatres of Lisbon , successfully copying the main characteristics from the artistic life of Lisbon of the time. More than pure illustration, one also finds small sequences, peculiar correspondences between what is said and what one sees. Describing or commenting with tenderness.

“He had days when he was so melancholic, so disconsolate, so irritable that even I, one of his closest friends, became worried for him”, Machado wrote .

“However, in between the shadows and melancholy, he continued to see in all things material for caricatures; things that escaped the eye of everyone else, jumped right at him. When we were working on the Theatres of Lisbon book I sometimes would ask him at certain points in the writing:

Does this make you think of a caricature?

That? Any number. It’s a goldmine!

And indeed, with these goldmines, the same happened as with the others: whereas the prodigal lose their treasures as they discover them, whereas the reckless never really see them and the vain are convinced that they are worthless, he masters the treasures of what he understands as his work, enhances himself and the public thanks him for it.»

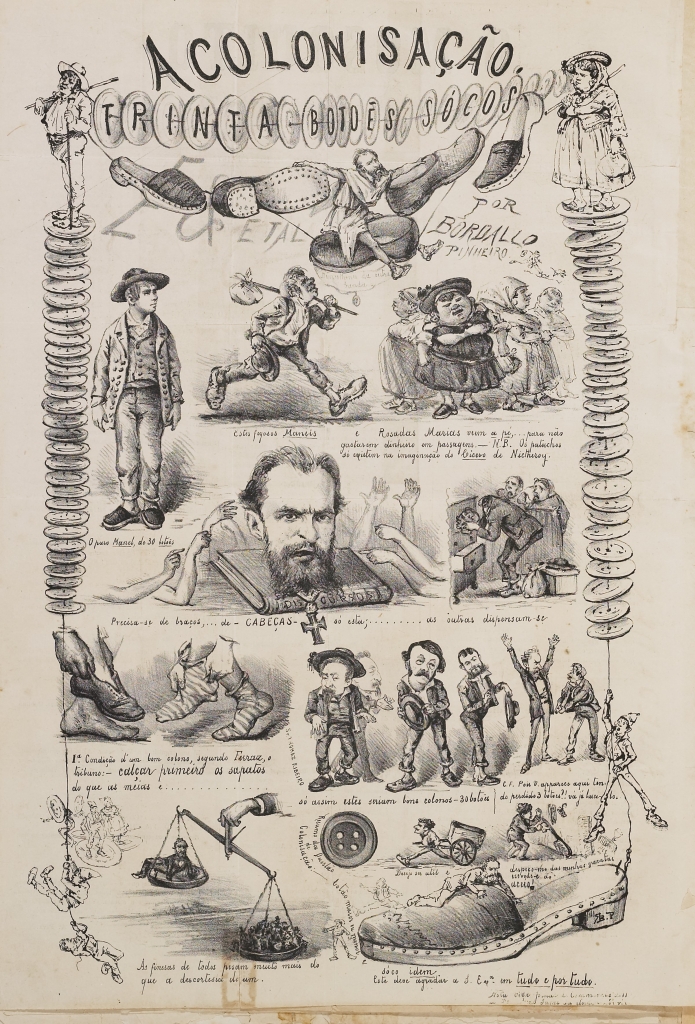

India ink and watercolour on paper

unsigned

ca. 1875

MRBP.DES.1200

One only has to look at the names to understand how productive and timeless a network of affection and collaboration Bordalo built up with “his” writers.

In launching A Lanterna Mágica he worked with Guerra Junqueiro and Guilherme de Azevedo (who both used the pseudonym Gil Vaz), the latter going on to work on O António Maria and the very successful Album of Glories (taking on the noms de plume João Rialto and João Ripouco). “At the height of a party he would suggest malevolent ways of ending the world; Bordalo would put the trumpet of final judgement to his lips and mockingly blow the sound of extermination. One was the explosion, the other the fuse: Bordalo the bomb, Guilherme the mystic candle.” The collaboration was thus described by the writer who replaced Azevedo when the latter left for Paris, the author of As Farpas who had praised a picture by a certain young man as the advent of social realism, and who now worked with him, despite their differences, only to confess later that he learned to write watching him drawing.

“He was a beautiful flower of full-blown talent in seeking and receiving the applause of the clubs, café and theatres, like a magnificently white lily against the confused darkness of a rubbish heap. I was, for all those diverse contacts from the world of journalism in Lisbon, that which I still I am today – a frightened hedgehog.

How lucky that, when once a week, on the eve of publication of our periodical, we would meet (…) nothing more divergent, nothing more antinomic than the criterion on which each of us based our opinion with respect to the event about which we had to produce, within a few hours, a harmonious and homogenous comment in terms of the drawing and writing. Imagine, on top of the dizzying depths of an alpine abyss, the meeting of two goats, horns against horns, on a footbridge only half a span wide and with no side railings. And thus was, for many years, the encounter of two opinions, that of the drawer and that of the writer of O António Maria.»

There then followed Alfredo de Morais Pinto (aka Pan or Pan-Tarântula), who stayed with him until Pontos nos ii, coinciding with Fialho de Almeida (Irkan), but leaving before the arrival of Eugénio de Castro (EU), amongst others, until the pages of A Paródia welcomed the young João Chagas (João Rimanso). In Brazil he also relied on the writing of José do Patrocínio in O Besouro. With them he hunted the types, with them he transplanted trees and pruned them, with all of them he planted seeds, spending hours at the table with them in discussions and all else that takes place between those working under the same roof.

The periodicals were a stage/home for Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro – at once a hiding place and a place to shout out loud, a place to expose oneself and to whisper. The greatest, most devious and disquiet of them was O António Maria (1879), extended by Pontos nos ii and the second series of O António Maria, the three then forming a whole. At the time, magazines were numbered sequentially, suggesting the idea of volume, a work in progress. The sections had fixed columns in graphic cadence and had on the centre pages and the cover exclamations, some of them in colour, a practice that ran through all publications. They featured highly illustrated texts (“chronicle of the week”, “charity section”) that became authentic narrative sequences. This “synthesis of good Portuguese sense touched by a happy ray of sunshine from that good peninsular sun” was to show the inventiveness of his art, the acuteness of his gaze. A style matured, covering the whole range of his topics, with the greatest of impacts. It was here that he came closest to what he considered his programme. O António Maria “will take all diligences to be correct, at the same time making titanic efforts to be funny, now and again. Possessed by these two ambitions it is clear that O António Maria had no remedy, in most cases, other than declared and open opposition to the governments, and open and systematic opposition to the oppositions, which by no means makes it impossible to be likeable some days, and full of courtesy in all issues”. A rose and some thorns.

A Lanterna and the periodicals produced in Brazil – O Mosquito, Psiit!! and O Besouro – were nothing more than a laboratory for the drawing and a school for the topics dealt with. A Paródia, a mere post scriptum when ceramics had already won him over and he was consumed by illness. The editorial of the latter does not hide this, assessing with exactness the phenomenon that infected everything and everyone – dances, theatre magazines, collars, cuff links, and also cigars, canes and hats.

“O António Maria, ladies and gentlemen, was the Regeneration, Fontes and his Circassian water, Ávila and his cache-nez, Sampaio and his pamphlet, Arrobas and his public notices, the Public Promenade and the lyricism of Mr Florencio Ferreira, Madam Emília das Neves, the “Jewess” and the Recreios Whitoyne theatre – a world coming to an end, a dead world of shadows, spectres, mummies, where we could only be at ease under the condition of having disappeared with it, which is evidently not the case.

Staying inside O António Maria would be like staying inside a museum, like an old guard showing the remains of a passed epoch to the curiosity of his time.

A Paródia is something different, as the times are different.

O António Maria was a man. At most it was a family.

A Paródia – let’s say it without fear of immodesty – is all of us.

A Paródia is caricature in the service of the great public grief. It is the Dance of the Bica in Prazeres Cemetery.”

Whilst in A Lanterna he published drawings by Manuel de Macedo and in the latter editions made space for other artists, even international ones, in addition to the growing help from his son, Manuel Gustavo , basically every room, piece of furniture and item of decoration belonged to him. The complete director even drew his guests/actors

Lithograph

Signed: “To the esteemed Actress Delfina, with the compliments of her admirer Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro, evening of 20 December 1873”

MRBP.GRA.1151

In the mad fervour of those years, the hunter turned to butterflies and registered the leading figures in his Álbum das Glórias , forty-two sheets, published in loose collections with colour printing and separate “biographies” in biting black. Although the large part of the work, sub-titled Volume I, took place between 1880 and 1883, the two following series of three drawings each, from 1885 and 1902, symbolically accompanied Rafael’s mature trajectory. The pantheon was announced as containing “statesmen, poets, journalists, playwrights, actors, politicians, painters, doctors, industrialists, salon types, men from the streets, institutions, etc.” Most of them were politicians; to begin with, individual government members and leaders of the Progressive and Regeneration parties, first and foremost his favourite Fontes Pereira de Melo, followed by writers and polemicists, or both, such as Eça or Gomes Leal, singers and actresses. And, of course, the inevitable Zé Povinho.

The spotlight of the recently arrived electric light identified the place of the characters in the energetic and musical Bordalian spectacle: the heart.

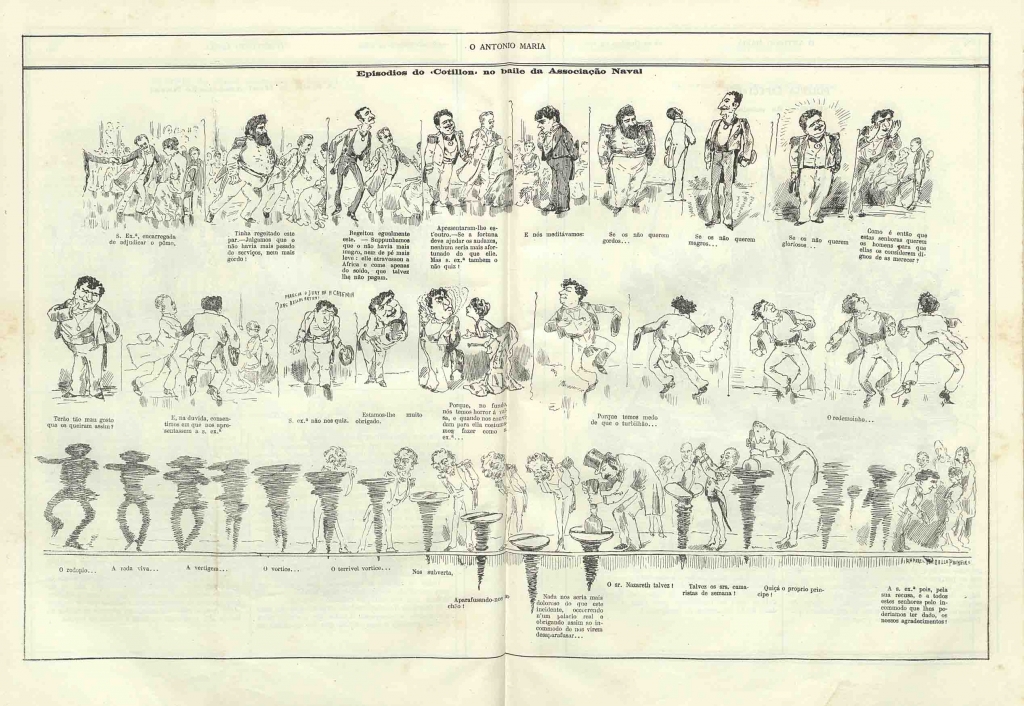

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 24.11.1881, pp. 372-373

MRBP.RES. 2.3

Body, the Stage for the Actor

“Thanks to a very special and entirely personal gift, he only needed to look at a human physiognomy for a few seconds for it, instantly drawn by the gaze, to remain burned into some corner of his brain, due to the most instantaneous receptiveness and most prodigious capacity for visual retention that I ever encountered.” That was, once more, the in vivo report by Ramalho. “Thus, conceived in the mind, the portrait was in his memory a kind of foetal acquisition, an indestructible embryo, a being that, at the first evocation of his will, he would birth, from the point of a pencil or a quill on to a sheet of paper. The creature would appear at random as at birth, on its feet, from the front, on its back or on its side. And the face of the specific person, reduced to the linear image, was, in Rafael’s fingers, a thing over which he disposed according to his most capricious whims. Once he took power over his individual, he forced it to do everything: he made it fatter or thinner, made it cry or laugh, ennobled it or dandified it, made it younger or older, made it upright or curved and bent, instilled in it a fearsome passion or a childlike fear; and without ever disconnecting it from its essential anatomical elements, allowing the figure to be always true to itself, personal and unmistakeable, he could make it a genius, a hero, an imbecile or a creep.»

There is no story without faces and masks, without the human figure in action. That thirst for recording the creatures on paper, twisting them into heroes or imbeciles, came early on. In private, challenging his father, Manuel Maria, on the school walls, before the public arrows aimed at the national failures and some moments of greatness. His targets themselves would not stop torturing him, stopping him in the street to ask that they be satirised. They even complained when their noses were exaggerated, or about perceived dissimilarities. Or they simply participated in the great homage of 1903. When someone questioned Hintze Ribeiro’s presence at the artist’s funeral, given that he was, along with Fontes and many others, one of Bordalo’s most caricatured figures, he replied:

— I was… Which is why, when I want to remember my political life, I leaf through Bordalo’s pages.

Bordalo’s pages are a gigantic gallery of portraits of politicians and artists, as recognisable as they were admired. When a death happened, and this was not only the case with Fontes, the matter became a serious one and the page contained a print with a certain degree of solemnity. But the rule was the bodies stretched into all forms and the quality of the abstract characters, some of them so strong that they practically became flesh.

Pencil drawing/watercolour on paper

unsigned/undated

MRBP.DES.1198

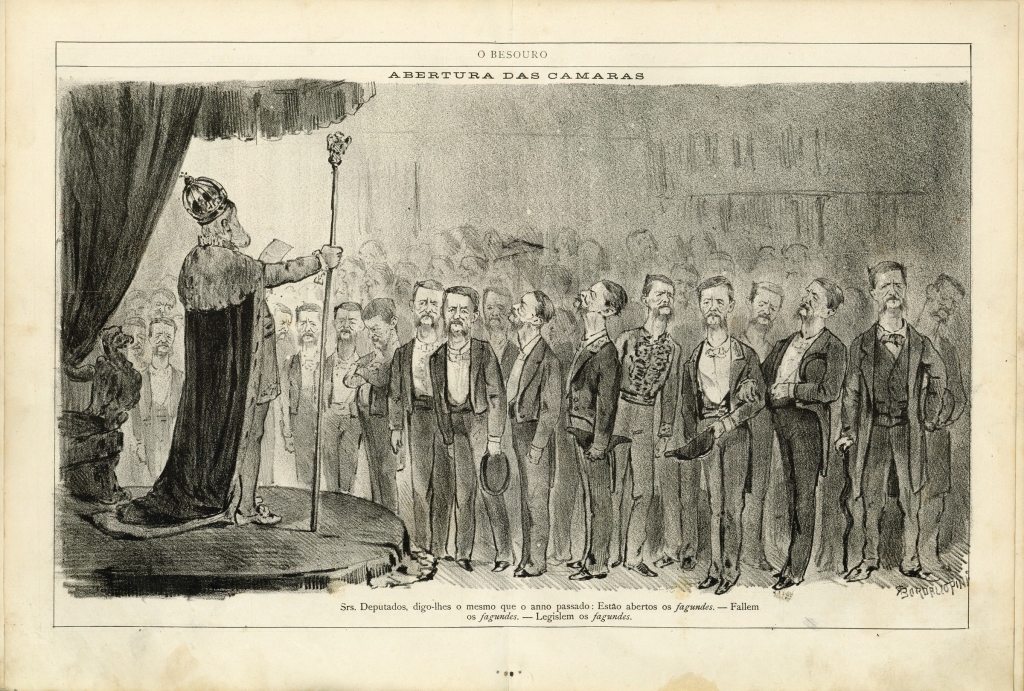

The country, represented by the caricaturists of previous generations as a skeleton, became rich in representations: naked, moribund, a gaunt cow, a metal donkey – an inexhaustible bestiary of metaphors, ending on a high with The Big Sow . And this without even touching on the metamorphoses of Zé Povinho, who, once tested in titles and illustrations, became the symbol of the people in A Lanterna Mágica . On the same pages the pot bellies appeared immediately too – the politicians/MPs who were little more than swollen guts. Later, in the Brazilian O Besouro, he invented the cloneable Fagundes, a small, mediocre parliamentary representative who is still part of the lexicon in that part of the world.

Lithograph

Signed: “Bordallo P.”

Published in O Besouro, 14.12.1878

MRBP.GRA.1277

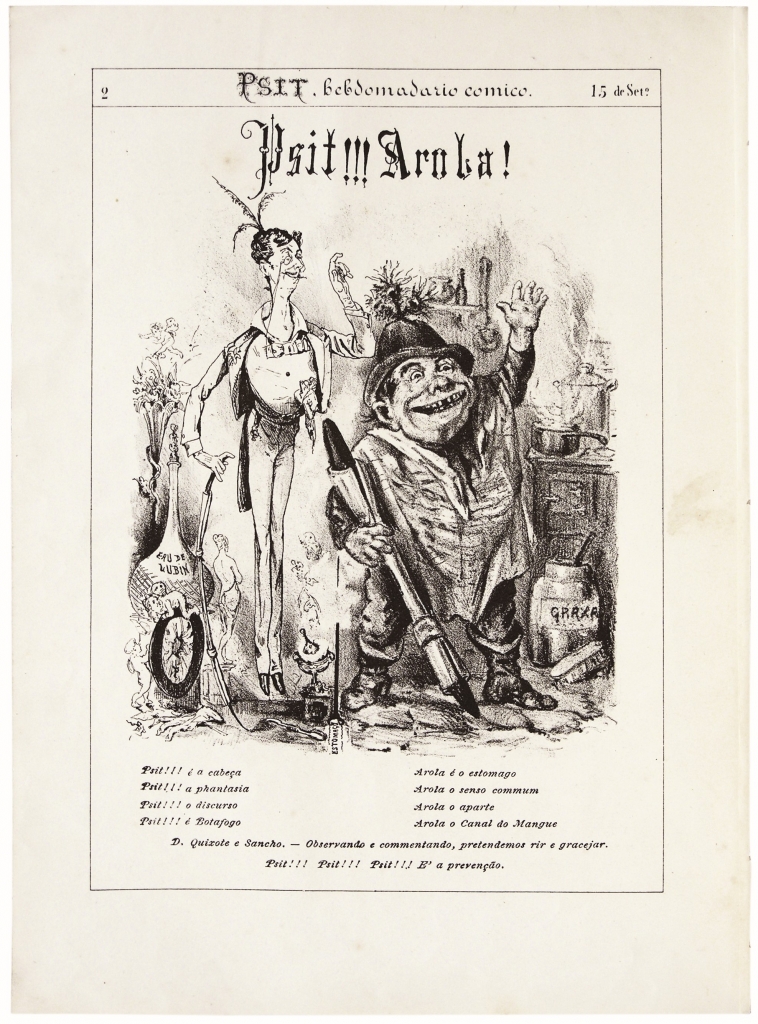

In Brazil he also found the inspiration for a duo of anti-heroes who were to be honoured in ceramics: the dandy in overcoat and monocle, Psit, was “the head, the fantasy, the discourse”; while the vulgar Arola was “the stomach, common sense, the aside».

Lithograph

Signed: “RBP”

O Mosquito, 18.12.1875, p. 2

MRBP.RES. 22.1

Lithograph

Signed: “RBP”

Psitt!!!, 15.09.1877, p. 2

MRBP.RES. 7

There he also left Manel Thirty Buttons, a provocative representation of the Portuguese emigrant. He also found inspiration early on in popular culture for the very resilient old woman with the headscarf, an embodiment of conservatism. This was before she became Maria da Paciência, used in the logotype for Pontos nos ii and possibly Zé’s wife.

He also applied the same truth resolutely to himself. The body became such a pliable material that he was transfigured into a cat. This feline alter ego, sometimes known as Pires, was only surpassed by the appearances of the artist as himself. self-irony of his, which achieved a notable connection with his readership, led him to draw himself in a complete range of sentiments and situations – a black man from Bié, a fat mandarin, a gorilla with a monocle admired and an admirer, trembling or crying, wearied or demonic, as a baby with a bib or an astronomer, pot-bellied or skinny, hanged, assaulted, sick. In strips and full pages, the feuilleton continued, he told of himself, his lack of inspiration, his indignation, his happiness, his diet, his tastes and every trip he made – in some cases reporting on the star’s reception he received, somewhere between the elegant dandy and carnival pantomime.

Pencil drawing on paper

unsigned/undated

MRBP.DES.1119

However, the “journalist of the etching and feuilletonist of the pencil”, in closing the first series of O António Maria, used the opportunity to affirm his sense of indignant individualism. “I do not belong to the congregation of journalists, which is why I am alone, and there are no groups consisting of only one person; I do not belong to the monarchist group because they call me a revolutionary; I do not belong to the republican party because they have branded me a sell-out!

Thus, as I can be neither a politician nor a journalist, I am going to be simply a worker – who, after all, may become something else as well.»

Lithograph

Signed: “Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

O António Maria, 28.10.1880, p. 352-353

MRBP.RES. 2.2

The Bordalian horizon had little of the worker and surpasses by far the hesitant approach of a Zé Povinho, who refused to rise up and overthrow the long procession of kings and queens, who did not know how to change the rules of an inert parliamentary system, where elections achieved little more than swapping out the heads on the puppets at the same little theatre . The artist was exasperated by his creature’s passiveness, as he was an advocate of the republic, although not always on the republicans’ side, just as he may have admired monarchists but did not join their cause. He looked at Marianne and saw, in addition to a beautiful woman, the progress that was essential for the preservation of an active nationality. Now we are at the very core of his cause, even in the arts: the nation. His graphic discourse was based on the hard-to-define and intangible idea of “Portugueseness”, with shades of Manuelism in decoration and decorativism. Hence, at every step, because of the “Ultimatum”, John Bull embodied like no one else Zé Povinho’s enemy and obsession, also the country’s obsession. Getting worse as he aged, he only found an equal cause in anti-clericalism, as the saw the Church as the ultimate conservative. “In Politics”, wrote Manuel de Sousa Pinto, “Bordalo is fundamentally republican, in matters of religion irreducibly anti-clerical; and as a citizen, sincerely egalitarian and on the side of the humble”.

The main struggle was that for freedom, which of course allowed for everything, above all paradox. Rafael Bordalo was a libertarian in all senses of the word, even in its meaning of bon vivant. He reported on daily life as if it were a permanent carnival, an opera that could not be taken seriously, a boisterous laugh in the audience that sounded like a moment of reflection. The debate of ideas was an inconvenience from time to time for the powers that be, battered as they were. In 1883, a version of The Last Supper with Zé taking Christ’s place, saw him end up in court. The aggressive reactions continued to increase and at one point the litigations were so numerous that Bordalo claimed he was setting up offices at Boa-Hora [location of courthouses in Lisbon] . Censorship, no matter what its form, took the appealing place of target figure. The noteworthy lampoon “What we would suppress” is an example of stylistic procedures in full synthetic force in the service of a cause – freedom of expression. A face could lose its tongue, mouth, ear, eye until it became a blank space. The individual is the exact opposite. Bordalo drew to tell a story, to tell of himself. Rafael danced in perpetual movement, a metamorphosis in delirium. See the strong image, the flesh-eating plant that pursued him from 1877 , when he was just a dancer who screwed himself to the dancefloor because of his vertigo: “Metamorphoses – The Delirium of the Waltz”. Years later , he was the spinning roundabout, the live wheel, the vertigo, the vortex, the terrible vortex. All of them tried to pull him out, even the prince. It was impossible. He was a screw/thorn in the side that required great delicacy to remove it.