A National Ceramics Factory

by Paulo Henriques

Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro arrived at ceramics by means of an erudite path and not via workshop experience, which was a decisive factor for the originality of his work.

Born into a family with artistic and intellectual interests, the son of the Romantic painter and sculptor Manuel Maria Bordalo Pinheiro (1815-1880), and one of eight siblings, the most well-known of whom was the painter Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro (1857-1929), Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro received his artistic education from his father, experimented with theatre in 1860 and attended – somewhat irregularly and without completing his studies – the Lisbon Academy of Fine Arts between 1861 and 1871.

By the time he first tried his hand at ceramics at the Sacavém Factory in 1883, he could already look back on a solid career as an artist and caricaturist, with his work published in Calcanhar de Aquiles and A Berlinda, 1870 and also in Álbum de Caricaturas: Frases e Anexins da Língua Portuguesa, 1875, the year in which he created his famous Zé Povinho character, followed by O Mosquito, 1876, Psit… and O Besouro in 1877 and 1878, No Lazareto de Lisboa and António Maria in 1879 and Álbum das Glórias in 1880. This publishing activity was to continue uninterrupted until his death, with the periodicals Pontos no ii (1889) and A Paródia (1900).

The Caldas da Rainha Faience Factory’s articles of incorporation were recognised in October 1883 and the public deed signed on 9 August 1884, the company becoming a private limited company whose founding shareholders were Feliciano Bordalo Pinheiro, who was responsible for the company management, and Rafael, who was in charge of technical and artistic matters .

According to the articles of incorporation, the factory’s purpose was to “explore the ceramics industry, in particular the faience segment”, producing “ornamental ceramic products and wall coverings and crockery products of the type manufactured in Caldas da Rainha, fine faience items featuring original prints for everyday uses and everyday tableware for the less wealthy classes”.

Production was also to include construction materials, bricks, glazed roof tiles and wall tiles, which were manufactured from 1884 onwards and were used in the construction of the firm’s own technical and commercial premises, decorative porcelain, whose manufacture began in mid-1885, and tableware, an undertaking assumed in 1888.

Water colour on paper

unsigned; undated

MRBP.PIN.9

The installation of the ceramics factory in a centre with such longstanding tradition and very singular output as Caldas da Rainha, was very much in line with two decisive aspects of Portuguese life at the time, both economic and cultural – achieving national progress through the development of technological systems for the manufacturing, and a search for identity references for being Portuguese, the latter becoming a fundamental issue for Portuguese intellectuals in the late 19th century.

Both these issues emerged with the Liberal movement from 1822 onwards and took on a more programmatic stature with their definitive affirmation from 1834 onwards. Fifty years later the industrialisation and development of communications in Portugal were now realities that allowed Portuguese intellectuals to compare national development with international progress at the “Casino Conferences” of 1871, and also allowed artists to import a contemporary aesthetic trend, Naturalism, which was disseminated from 1879 onwards following the return of the painters Silva Porto and Marques de Oliveira from state scholarships in Paris and was made a generational movement by the Leão Group exhibitions from 1881 onwards.

Said group was led by figures such as Silva Porto, as “divine master”, José Malhoa, João Vaz, António Ramalho, Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro and Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, the eldest of the group.

Following a sense of disquiet derived from Romanticism, the group sought the genuine origins of Portuguese identity through deeper knowledge of the people and their traditions and a revaluation of cycles of the nation’s glorious history.

The choice of Caldas da Rainha was a result not only of the town’s long tradition in ceramics production but also the specific characteristics of its output, which was full of imagination and communicative force. From the 1820s onwards, one figure that stood out was the mythical Dona Maria dos Cacos, a manufacturer and distributor of monochromatic glazed clay figures, human and animal, that were used as jugs, toothpick holders and candlesticks. In 1853 Dona Maria sold her models and workshops to Manual Cipriano Gomes (1811-1905), known as Mafra, a great ceramics manufacturer who was to be made a purveyor to the Royal Household by King Fernando in 1870, allowing him to use the symbol of the crown above his own mark.

Converging with the taste for anthropomorphic and animalist figuration already rooted in Caldas da Rainha, Manuel Cipriano Gomes Mafra added the cosmopolitan taste for the revival of faiences by Bernard Palissy (ca. 1510-1590), a ceramicist whose writings were republished in Paris in 1844 and whose models were revived, mainly by Charles-Jean Avisseau (1795-1861) and Joseph Landais (1800-1883), who produced pieces that were manufactured in Tours and shown to great acclaim in the French section of the Great Exhibition of London in 1851 . José Palha probably brought Mafra back some of those models, possibly those known as rustiques in France, which featured exuberant ornamentation in moulded relief epresenting leaves, fruits, flowers, fish, insects, reptiles and amphibians – typical elements of the decorative ceramics in the Palissy style. Gaining the attention of the royal family and achieving a rich and varied production, Manuel Cipriano Gomes Mafra was the immediate predecessor to Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, both in terms of commercial success and aesthetic propositions.

In 1884, the latter was occupied with painting some powdered stone pieces at the important Sacavém Factory, the most modern of the day in Portugal.

Powdered stone faience

Inscription: “To the distinguished actor Augusto on the night of his artistic celebrations at the Theatro da Trindade, 21 May 1884. With the compliments of his friend, Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro”

MRBP.CER.5

Those pieces were dedication plates, one of them to the actor João Rosa that was signed and dated 21 March 1884. It featured a background of text in elongated handwriting and the actor as Cardinal Richelieu branding a sword, towards which, Bordalo Pinheiro himself, notably smaller in stature, advanced riding a cat and offering a bunch of flowers. Another plate, also made of powdered stone but produced at The Gomes de Avelar Factory in Caldas da Rainha, was dedicated to the actor Augusto in May 1884. The base of the plate features the actor standing wearing a dress coat and standing on a pansy flower whilst holding two bunches of flowers. The rim is filled with a dedication inscription in cursive handwriting. These decorative compositions – one unusual, the other more conventional – are rooted in the universe of drawing and graphics for which the artist had already gained note. The fact that the medium was now ceramics does not seem to have influenced their material conception.

The adoption of the more specific language of ceramics manifested itself later in pieces produced by the Faience Factory that can be attributed to the Palissy style but also revealed very different aesthetics, as we will see.

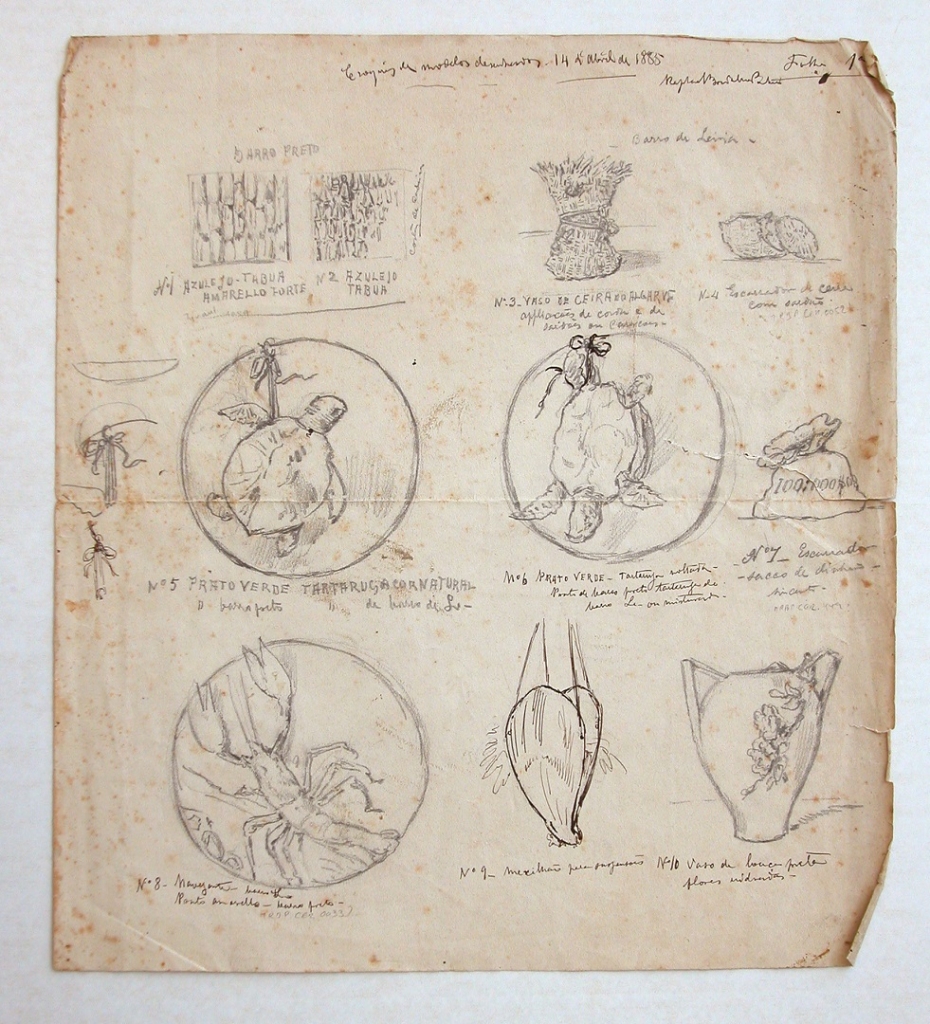

As could be expected for a man of talent with an extensive graphic output, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro applied the practice of drawing to the conception of his ceramics pieces, both in preparation sketches for individual details and for studies that were close to the final composition. His drawing became an essential tool in the conception of models. Some of the drawings are now in the collection at the current Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro Faience Factory in Caldas da Rainha, whilst others can be found in the Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro Museum in Lisbon.

Pencil drawing on paper

unsigned/undated

MRBP.DES.191

Indeed, both the use of drawings and modelling of the clay based on models taken from nature, essentially plants and animals, were established as standard practice for the production of prototypes at the new factory. These were developed not only by Bordalo Pinheiro but also workers specialising in the moulding of the pieces, the aim being that those skills could be passed on to future apprentices.

This echoed the approach by the Arts and Crafts movement, which was begun in Britain by the young William Morris (1834-1895) in response to the mass production of everyday objects, presented at the Great Exhibition in London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, and to the growing anonymity of the men and women who produced said objects, leading to the loss of creators’ marks and the signs of the inherent and essential human involvement.

Furthermore, the utopian project of the aesthetic configuration of everyday life as a whole was currently an ongoing development, for which, according to Ramalho Ortigão, “architects, painters and sculptors devote themselves, patiently and humbly, to designing models for all industries”, concluding with a reflection on the national reality that “Rafael was the only man, the only one who devoted himself entirely in Portugal to an arts and crafts industry, keeping it competitive with similar industries in the rest of Europe and turning it into a new source of wealth and national glory” .

In addition to introducing a modern, national aspect to the traditional ceramics industry, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro extended his activities to formal teaching, creating links between the industry and the learning of the trade at the Caldas da Rainha Industrial School. The training was seen as recompense for the support the government gave the factory and established itself as an innovative practice in vocational training in Portugal.

The “national glory” so desired by Ramalho Ortigão also included the establishment of modern identity symbols for the nation. Indeed, many ceramics pieces produced at the Faience Factory served that purpose at the time and today form part of the collective heritage of Portuguese artistic culture.

Following the initial manufacture of construction materials, the first decorative faience pieces appeared from mid-1885 onwards. They can generally be described as following the Palissy style. One can recognise the typical use of modelled relief ornamentations in perfect volumetric balance, with a finishing in a naturalistic mimetic style representing botanical motifs – vegetables, cereals, flowers, fruits and algae – and animal motifs, both live – birds, poultry, insects, amphibians and reptiles – and dead and intended as food – fish, seafood, dried cod and game.

However, beyond these isolated ornamentations on the pieces or their adoption as a whole, in an approach not so far removed from the Mannerist fevers of Arcimboldo, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro stayed true to the ceramics medium, clearly revealing the type of object – plate, jug, pot, terrine, pitcher – at all times and giving it visual autonomy in terms of finishing by sticking to one and the same process, at times covering them fully with an homogeneous coloured enamel or using the dripping technique and other times, though less frequently, applying life-like textural finishes such as moss and sand textures.

It was on top of these prepared bases that the moulded ornamentations were applied with conceptual transparency and elegance: a single sprig or branch with flowers or fruits hanging or resting on the base of a plate or arranged along the rim; more elaborate bunches of flowers and fruits that occupy the centre or, with heightened complexity and formal autonomy, are transformed into veritable still lifes, recalling the bodegóns so dear to Spanish painting, except that those by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro were composed on large decorative plates.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP 1897”

MRBP.CER.252

By highlighting the form and the ceramics material as the background for isolated botanical references, which were represented in a hyper-realist mimetic style, the artist created refined visual dialogues that recall Far Eastern aesthetics, particularly the influence of Japan. Japanese influence had spread in Europe after the country opened its borders to the West in 1854. It reached France in particular in the 1870s, with the invasion of Japanese ornamental articles later leading to their integration into European taste, as part of a general trend towards Japanese styles which, understandably, also affected Portugal.

Whilst this trend would seem to permeate some of these pieces, one can also identify concepts that were dear to Naturalism, not only in the use of botanic elements presented in a mimetic style and the rural nature of the references used, but also in the suggestion of the capture of a moment, known as instantaneity in photography, but here registered in ceramics – the casual gesture of decorating an everyday object with a sprig or bunch of flowers or fruits. Once again combining the figurative ceramics tradition of Caldas da Rainha and the spontaneity desired by Naturalism, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro inscribed in some of his pieces an everyday narrative significance, with a high degree of liveliness and verisimilitude, skills that he had developed as a humoristic artist.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR”

1890

MRBP.CER.676

The round box with a lid covered with the luxuriant foliage of a loquat branch, with a small monkey eating the fruit forming the lid handle, could easily have been a domestic scene in the Portuguese interior in the 19th century, the monkey having been brought from Africa as a fun pet for a family.

The nationalist roots are also revealed in the decorative motifs used, be they: floral motifs, such as sunflowers, roses, lilies, magnolia, daisies or honeysuckles; individual fruits or fruits hanging on the branch, such as loquats, chestnuts, cherries, peaches and grapes; vegetables such as cabbage, cucumbers, peppers, turnips, tomatoes, garlic or potatoes; live animals such as cats, dogs, doves, monkeys, chickens, ducks, frogs, beetles, bees, snakes and lizards; or dead animals presented as food, such as lobsters, mussels, oysters, groupers, bream, sea bass, sardines, eels, dried cod and game animals.

These elements, which would be added to the object with a certain degree of autonomy, were also included in elaborate still lifes in frontal compositions, which, recalling examples from painting, were paired with other domestic, rural or marine motifs, such as white cloths and fishing nets, baskets, wicker bottles and fishwife baskets, all depicted in rigorous material detail, either whole or sections thereof.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR” and “FFC”

1901

MRBP.CER.0294

The painting genre still life was composed in the ceramic medium of the plate, the same being the case for the landscape, which featured representations of rural scenes presenting poultry birds or, in a more subtle allusion, forming a background of sky for birds in flight or perched on branches, or water for fish and amphibians.

The mimetic setting, a naturalist strategy par excellence, reaches maximum effect in pieces that simulate real objects as if forgotten in the everyday space, as is the case for baskets with fish. Particularly common was a esparto grass hanging basket containing two dried cods and onions with a string of garlic, a life-like depiction of traditional ingredients that represented a kind of exhibition of the best of Portuguese cuisine. The ceramics also incorporated daily life and objects, in the form of true-to-life replicas of material realities, with the glazed clay rigorously made to look like wicker baskets on a natural scale, esparto grass or wicker fans that served as note holders or boards hung on the wall, a canvas slipper visited by a little mouse or, now moving away from the rural matrix and revealing Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s more cosmopolitan experiences, a delicate lady’s glove forming a cup or a gentleman’s top hat with gloves resting on it in the form of a vase, possibly a reminiscence of the end of a dinner in a café in central Lisbon or a night at the opera in the São Carlos theatre.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR”

1892

MRBP.CER.0951

Exploring the specific capacities of the ceramics of Caldas da Rainha, applying all its techniques and imagery, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro also analysed it as a profound reference for a popular culture, a medium for a national taste and art, a perspective founded in Romanticism but still having the maximum ideological relevance for Naturalism.

An example of this are the series of pieces that directly reinterpret the theme of moulded reliefs applied to pottery forms, such as the three-handled jug in glazed monochromatic clay (but now in a strong blue shade) in the old style of Caldas da Rainha ceramics decorated with rosettes and a sinuous branch, or the beautiful censer in the form of a calabash, with the round belly decorated with moulded rosettes, alternating in size, and a lizard wound casually around the neck.

Reference, albeit with more austerity, is also made to the unmistakeable forms of traditional Portuguese pottery, subjecting them to modern formal interpretations in terms of configuration, extending the recipients’ proportions or giving sharper angles to the handles, as well as in the application of smooth and dripping enamels and isolated decorative applications such as small frogs or branches with flowers or fruit. The silversmiths of Lisbon were even commissioned to produce silver appliqués with lacework ornamentation and letters, the consummation of the ultimate paradox: forms inspired by popular pottery ennobled with ornamentation in precious metals.

Faience

no mark; undated

MRBP.CER.270

In line with this taste the Faience factory produced pitchers, jugs, mugs, round-bellied jugs with one handle, jugs with two handles, a lid and drinking cup, and even pieces that were less common in rural usage such as the modest clay jugs used for collecting water from wells and water wheels.

This strategy also served to inscribe modern identifying features of Portugal, reinterpreting the old pottery forms, the subject of systematic study by Joaquim de Vasconcelos in the same period, a catalogue of ancestral objects that developed slowly over time, making them a guarantee of historic proximity to the most genuine origins of the nation.

This fin-de-siècle nationalism also led to a revisiting of the country’s history, recalling glorious moments of the past, with particular emphasis on the heroics of the Portuguese Discoveries. An example of this was Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s participation in the World’s Fair of 1889 in Paris, where his ceramics enjoyed remarkable success and for which he designed the decoration for the Portuguese pavilion, earning him the honour of being made a legionnaire the Legion of Honour by the French state.

For the pavilion he opted for rustic, historicist evocations of Portugal, the showcasing of ethnographic and gastronomic references and reinterpretations of the art of the reigns of King Manuel and, by official order, João V . Some of the glazed tiles used in the restaurant area have survived. They reveal coarsely modelled reliefs and the circular lacework pattern of Spanish-Moorish inspiration but “reproduced from Batalha” , with the centre featuring four historical shields of Portugal, the reliefs standing out from the white background thanks to a vivid and very dark manganese shade.

This revival of artistic forms used during the reign of King Manuel I was to feature in diverse variants in the production of glazed tiles at the Faience Factory, repeating the geometric Spanish-Moorish interlaced motifs, star-shaped polygons and pied de coq patterns, but featuring very high relief and not just low ridges. This technique was also used in Renaissance motifs simulating textiles, ironwork and vine leaves, copying unique pieces such as the indented platband decorated with ears of corn alternating with grapes and vine leaves or the glazed tile with the armillary sphere, originally produced in Seville in the early 16th century for the Royal Palace at Sintra.

It was in this aesthetic context, simultaneous with the neo-Manueline decoration produced for the Portuguese pavilion at the Colombian Exhibition in Madrid in 1892 that Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro conceived, in 1891 , one of his most programmatic pieces, the famous Talha Manuelina [Manueline Carving], described in great detail by Fialho de Almeida following a visit to the artist’s studio and acquired by King Carlos in 1893.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR” and “Raphael B. Pinheiro”

1892/3

MRBP.CER.929

Based on the preparatory drawings in the Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro Museum collection, the final piece did not differ much from the initial designs which brought together, in a wildly eclectic style, references to traditional pottery – with the large rounded belly inspired by the pitchers used by rural folk, decorated with a line of Manuel arches, which are interrupted by four medallions, two under the handles featuring maritime exploration themes, and one each on the back and front featuring portraits of Henry the Navigator and the poet Luís de Camões. The medallions are crowned by armillary spheres topped with the Cross of Aviz, from where symmetrical rope decorations develop into the piece’s handles. Where one would expect the opening or lid to be, one unexpectedly finds, somewhere between a model for great architecture and a piece of fine jewellery, a hexagonal temple with Manueline arches and a rustic roof of Portuguese tiles featuring winged figures at the corners and crowned by another armillary sphere and the Cross of Aviz.

The base also features elaborate carving. It is a quadrangular plinth resting on four reclined lions, with the corners imitating cut stone topped with historical shields of Portugal surrounded by algae. At the centre of each side, the arms of Queen Leonor hanging on rope are set against a background of tiles identical to those produced for Paris in 1889.

The excellent technical virtuosity of the piece is beyond debate. It served a nationalistic iconographic programme that was encyclopaedic in aspiration. According to Fialho de Almeida, it associated “traditional water vessels that girls from Coimbra brought to the well”, “the drinking cup Gil Vicente would have made from drawings by Garcia de Resende”, the “implausible expressiveness of the Monstrance of Belém”, “Gothic chapels with perspectives of small columns, ending in an ogive, updated and very delicate…” and, referring to the sculptural groups depicting the Passion of Christ, “microscopically small statues reproducing part of the sculpture Bordalo made for Bussaco” .

There is an obvious misalignment between the whole formal construction and the ceramics medium, taken here to material absurdities of the miniaturist details and structural inadequacies, one example being the obvious physical fragility of the handles, which, in purely functional terms, were meant to be used for handling the piece. Likewise there is a clear incompatibility between the modelled ornamentations and the actual decorated object, with architectural details worked in miniature and the disconnected combination of scales, and between the carving as a domestic object and an architectural finish referencing a monumental scale.

In the same spirit Bordalo was to create another “jewel” of technical virtuosity and formal eclecticism in 1896 – the Arab Censer, a piece he dedicated to the counsellor Júlio de Castilho as a sign of his gratitude for his support in one of the serious financial crises that afflicted the Faience Factory.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP 1896”

Inscription: “To Counsellor Julio de Vilhena, as a sign of my gratitude. From Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro Caldas da Rainha 1896”

MRBP.CER.368

The theme of lions, now featured on the front, reappears on the lower section of the belly covered in Spanish-Moorish inspired tile motifs. The upper section is decorated with an extremely delicate lacework surface that mimics filigree work, a technique that involved very fine strips of clay, and also forms the two handles. On the belly, central aediculae feature finely detailed miniature representations of two scenes from the Passion designed for Buçaco. The lid, in the form of a spherical cap that closes the round opening, revisits the Spanish-Moorish themes and features a handle in the form of a sitting lion.

As with the Talha Manuelina, the Arab Censer seems to embody a contrarian attitude to the concepts of formal coherence, economy of technical resources and unity of form and decoration, all of which were advocated by the theoreticians of the Arts and Crafts movement and were also of interest to Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro in more everyday pieces.

He revealed this modern concern with improving the quality of industrial production for general use by the public, a democratic approach, through the design of good ceramic objects in technical and aesthetic terms, in the lines he designed for dinner services. These showed formal preoccupations with industrial manufacture and decoration in powdered stone, produced in powdered stone and decorated with printed motifs that, in general, alluded to Portuguese references, or were painted in a more international style akin to Art Nouveau

Powdered stone faience

Mark(s): “FFCR- Caldas da Rainha”

1902

MRBP.CER.380.01, 380.02 and 380.03

Indeed, when working on pieces that were to be of great ostentatious value and aimed at a public with a higher social standing, the artist employed unsurpassable technical virtuosity and accumulated erudite references in profusely eclectic associations. The final outcome was grandiloquent and emphatic, but problematic in terms of formal harmony and of dubious artistic effectiveness.

The same approach can be seen in the famous Beethoven jug, currently in the Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro. A neo-Rococo fantasy measuring 2.8 metres in height and featuring a complex iconographic programme that alluded to the universal composer, the jug was produced between 1896 and 1898, originally for Carlos Relvas. As its size made it impossible to be kept in Relvas’s home, Casa dos Patudos, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro took it with him on one of his visits to Rio de Janeiro. He was proud to present such a daring technical accomplishment with bizarre miniaturist decoration and ended up gifting it to the President of Brazil.

This technically and artistically ambitious piece has an international cosmopolitan influence – the revival of a French 18th century style – and is grandiloquent in expression in line with its purpose, an homage to Beethoven, a theme that agreed with the well-known musical interests of Carlos Relvas.

The monumental piece was part of the eclectic revivals of international styles that merged the complexity and sensuality of Baroque compositions – dynamic forms and mimetic descriptions of anatomies, faces and animals, plants and waves – with images that came from Mannerism, the Baroque and Rococo – decorative written panels, the use of winding acanthus leaf ornamentation, garlands of flowers and fruits, and confrontations between chimeras and putti, Tritons and Nereids and fauns and nymphs.

This formal and figurative cast was to be used once more to commemorate the Portuguese glories of the Discoveries in the “Renaissance Centrepiece”, a surprising bowl that rises from the twisted tails of two sea monsters whose heads form the handles of the piece. The bowl itself features frenetic representations of figures having tails of acanthus, perhaps Nereids and Tritons, a direct allusion to the Portuguese seas.

Faience

Mark(s): “R. Bordallo Pin 1894”

MRBP.CER.142

The same theme features exuberantly on the “Renaissance Candle Holder”, a tumultuous composition that begins with dolphins with intertwined tails, followed by two nudes of mythological inspiration, one man and one woman, a belly decorated with Spanish-Moorish tiles out of which four candlesticks rise in the bizarre form of torsos of Atlantes and Nereids amidst swirling acanthus and waves. The fifth and central candlestick rises higher than the others, decorated with putti and finished off with sea monsters.

The suitability of these pieces for sophisticated ambiences of the day, a sign of the taste most appreciated by the Portuguese elite classes, is also clear in the mounted timepiece Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro made for the publisher Manuel Gomes. It represents a maritime apotheosis of Tritons and Nereids amongst agitated waves and is crowned by an eagle carrying a goddess holding a torch with an inscribed banner flying from it revealing a quotation from Camões, “(My song) shall sow through the world’s every part”.

This revivalist trend, which bore the name Renaissance but featured motifs closer to Mannerism, was deemed sophisticated enough to be included in the most refined interior decorations in Lisbon’s best houses. One example was the fireplace frieze which, as confirmed by the ceramics specialist José Queiroz, was produced at the Faience Factory in 1903 for the palatial residence of the conductor Miguel Angelo Lambertini built on Lisbon’s Avenida da Liberdade in 1900 in a style reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance, a refined work by the Venetian architect Nicola Bigaglia.

Almost a decade earlier, in roughly 1892, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro had produced particularly noteworthy decorative pieces for the dining room in the Beau Séjour residence in Benfica. A large washing fountain and a chandelier adorned in a realistic naturalist style, somewhere between Palissy and Caldas da Rainha, with a great profusion of fruits, flowers, sea molluscs, fishes and, as a definitive brand image, lizards and frogs. Although they are an earlier creation, this pair heralded other requirements of the wealthy bourgeois taste, those deemed convenient for an upper bourgeois residence that could almost have been a summer home given its peripheral location in relation to the more cosmopolitan centre of Lisbon, guided by domestic architectural design.

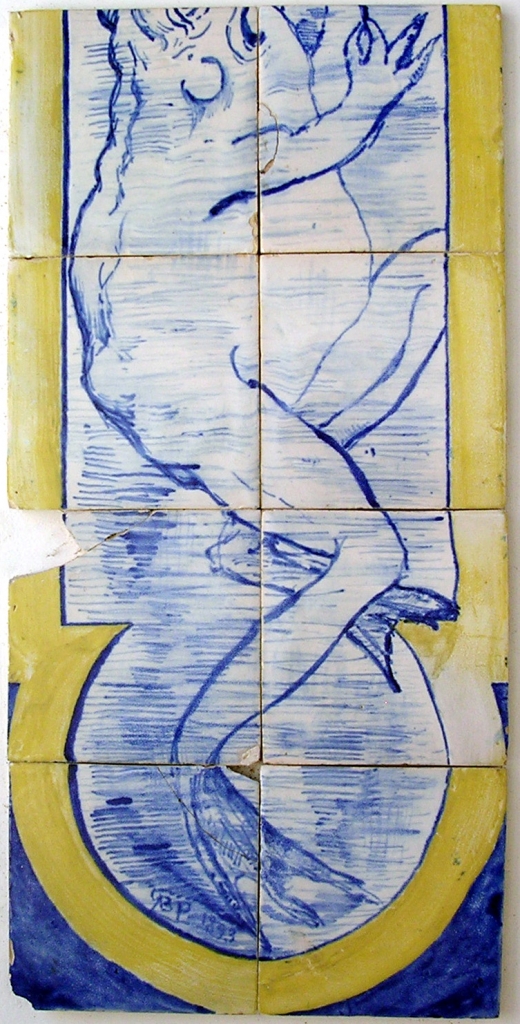

Faience painted blue and yellow

Mark(s): “RBP 1893”

MRBP.CER.18

For the two façades of the refined tobacconist’s Tabacaria Mónaco, one facing Rossio and the other Rua 1º de Dezembro in the elegant centre of Lisbon, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro designed scenes with frogs, storks, snakes and birds in 1891. These motifs once again reveal rural references but here they take on the additional value of human stories told in the form of fables, depicted in a free painting style in cobalt blue on glazed white. Some of the tiles in the Museum’s collection may have served as tests for this work, such as the one featuring Velha Maria [Old Mary] in flight and a frog sitting beside a pond.

When Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro turned to ceramics his output in the field of graphics and caricature, which he began in 1870, had gained public recognition for its power of observation, originality of perspective and pertinence of commentary. As it was a question of not only artistic practice but also, and above all, of critical temperament, the artist found in the ceramics of Caldas da Rainha many of the values he had explored in cartoons and political commentary: the desire to depict personae and tell stories, and show irony and the ridiculous and, finally, an irrepressible communicative impulse.

And so the artist and drawer transferred to the ceramicist many of his creations, the most emblematic of which was Zé Povinho, a figure created in 1875, followed by Maria da Paciência and a whole cast of popular figures such as fishwives, policemen, priests and sacristans, and bourgeois dandies and elegant figures, as well as diverse figures from the country’s political and social spheres.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR”

1895

MRBP.CER.389

Moving from drawing to ceramics had certain consequences for the conception of the images, not only in terms of the switch from two to three-dimensionality of form but also in terms of the research Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro had to carry out into the expressiveness of the new medium. This was particularly made evident in the charismatic self-portrait in the form of a whistle from 1903.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP1904”

MRBP.CER.391

This huge array of figures, a collective portrait of Portuguese society at the turn of the century, was transferred to diverse functional objects such as whistles, bottles, boxes, ashtrays and ink wells, and they took on a life of their own as original movement figurines.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP 1903” and “FFCR”

MRBP.CER.488

These figurines were able to make movements that to some extent imitated the movements in real everyday life. Generally speaking, they were built with different pieces resting on each other. The first piece consisted of the base and feet of the figurine, ending in a cone of modelled clay, upon which the second piece was placed. The second piece was normally the trousers or skirt, torso and head of the figurine, whereby the torso could also be a separate piece ending in another cone, on which the figurine’s head was placed.

This unstable structure of minimal support points meant that when touched each figurine moved in its own peculiar way, revealing movements of the head and body that added to the playful characterisation of the modelled and glazed figure an additional and unexpected comic element.

This passage from cartoon to ceramics, achieved with great formal intelligence, was also developed on another level by means of a reinterpretation of the functional codes of ceramic objects, which was made clear in the use of spittoons and chamber pots, utilitarian utensils of less noble status, to represent, in a biting and playful tone, despicable figures such as the moneylender who grows rich on the high interest rates charged to people in financial need, and John Bull, an emblematic figure for the United Kingdom, the country with the oldest alliance with Portugal which had inflicted upon it a huge national humiliation with the Ultimatum of 1890.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR”

1890

MRBP.CER.445

Likewise, other real-life figures inspired him to create symbolical functional objects, such as the bottles representing Gungunhana Before and Gungunhana After (ca. 1895), Gungunhana being an African chief who resisted the Portuguese colonial powers, and the toothpick older in the image of the Viscount of Faria, the Portuguese commissioner to the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP Caldas 1900”

MRBP.CER.364

The same sense of irony, based on the adoption of functional, daily use objects to social or political caricature, was also the inspiration behind the noteworthy series of Chinese people, bullfighters, English policemen and fine ladies and dandies taking the form of tea pots and cups that were produced at the Faience Factory from 1897 onwards.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP Caldas 1897” and “Bordallo Pinheiro – Portugal” (MFABP Lda.)

MRBP.CER.358

The commission by the minister Emídio Navarro of groups of sculptures representing the Passion of Christ for the chapels at Bussaco in 1886, a work that was neither completed nor delivered, marked the beginning of Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s work with large-scale ceramic sculpture. Again, coming from outside the world of sculpture, he raised questions of modernity, or a lack thereof, that the contemporary Portuguese sculptors, who trained in the Portugal academic system, were unable to address.

To begin with, the question of the use of colours in sculpture, which accentuated the imitation of flesh and materials. This was followed by the use of exotic, Orient-influenced imagery that was reconciled by the narrative of the Passion. Both of these situations are clearly evident in the groups of sculptures at the José Malhoa Museum in Caldas da Rainha.

The life-sized statue of a young black man wearing only a grass skirt is also a sign of this exoticism and, above all, a decadent fin-de-siècle trend. Exquisitely modelled and polychromatic, the piece was not cold painted but was the result of merging of the glazed pieces. A rarity in the output of the Faience Factory, this piece was designed for a garden, which is the most probable interpretation, given the almost naked state of the figure, or for an eclectically decorated living room. Exotic figures flanking a doorway, alluding the other races, became common in cosmopolitan, elegant circles in Europe in the 18th century, with the trend continuing to the late 19th century in the pompier style, which, given the Portuguese colonies in Africa, was also popular in Portugal.

Faience

Mark(s): “FFCR” and “RBP”

1904(?)

MRBP.CER.939

In addition to these large-sized pieces, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro also produced a series of busts, which were conventionally cut off at the shoulders and chest, and supported on stands. Whether in plain clay or polychromatic, these were naturalistic portraits of popular figures such as Pae Paulino (1894) or the head of a young black girl and illustrious Portuguese personalities such as Guilherme de Oliveira (1895), Dr. Sousa Martins (1899), Eça de Queirós (1901) and Tito de Carvalho (1902).

One noteworthy portrait of a lady, possibly the actress Maria Visconti, dated 1899, stands out for its exquisite modelling, with a dynamic edge added to the bust by the head turned to one side, the woman gazing poetically into the distance, and the hand on the left side of her breast holding the veil around her head. It is a posthumous tribute to this exquisite woman who had died the previous year and was much loved by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro.

Painted clay

Mark(s): “RBP 19 February 1899”

MRBP.CER.369

Although previous models remained a part of current production at the Caldas da Rainha Faience Factory, created in the eclectic moulds of Naturalism and diverse stylistic revivals, both national and international, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro entered the 20th century, approaching the end of his days, with the most modern propositions in the world of ceramics in Portugal, clearly Art Nouveau influenced in their definition.

The Bowl with Dragonflies (1901) surprises with its formal intensity and modern language. It is an oval recipient richly decorated with leaves, ending in large handles made up of voluptuous daisies. The daisies are repeated at the shorter sides, serving as background for a large dragonfly. The bowl’s fluid configuration and its modelled decoration are of great formal and iconic refinement. The organic lines and natural references typical of French-inspired Art Nouveau, such as the thick-stemmed, sinuous flowers and the graphic schematism of the large insects, are decorated in the old faience technique in a palette of green, yellow and white shades, which contrast with the rich materials for the dragonfly wings, where the painting imitates their natural iridescent properties.

The same can be said for the finely modelled grasshopper tiles that repeat the graphic rhythms of curve and counter-curve and create an almost abstract diagonal pattern; and of the beautiful tiles that feature butterflies resting on an ear of wheat, which combine the rural reference to the cereal and the animals that can destroy or celebrate it.

In the early years of the new century, as part of a campaign for the improvement of urban commercial spaces, which included, in particular, the bakeries, the Faience Factory produced the ceramic decoration for Panificadora de Campo de Ourique [The Campo de Ourique Bakery], the windows of which were decorated with unique compositions featuring reeds, poppies, birds and lettering, decorated with repeating tile friezes featuring a butterfly inside a circle between ears of wheat, tiles with butterflies resting on ears of wheat and, on the counters, tiles with grasshoppers on ears of wheat.

Polychromatic enamelled clay

Mark(s): “FF Caldas” and “RBP”

1905

MRBP.AZU.5

This adjustment in formal conception, very much in line with modern international decorative tastes, did not reject domestic rural imagery and the country’s rural riches. The changes brought about by Art Nouveau were manifested in the ceramics produced by the Faience Factory under Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s guidance not only in the morphological representation of these objects, which came to represent the company’s image that disseminated internationally and in the wider field of the decorative arts.

Faience

Mark(s): “RBP Caldas” and “RBP 1902”

MRBP.CER.0343

Other investigations into the abstract expressivity of ceramic materials, be they pastes or the glazed materials, even if they were not carried out in great depth by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, were reflected in small-scale pieces such as the jug with fish (1901), decorated in muffle colours, in which the glazed enamels and ceramics technologies are manipulated to create unexpected visual looks.

Faience

Mark(s):”RBP” and “FFCR”

1902

MRBP.CER.0669

For the dragonfly bowl the designer simulated those qualities using majolica painting on the insects’ wings, thus imitating the iridescent glazed look so appreciated by international ceramicists of the time. In other large-sized pieces, it is evident that experiments were carried out with firing in reduction atmospheres, and glazes and enamels with faults that could produce “cracked” effects. This reflected one of the most promising paths for modern ceramics of the early 20th century – that of the abstract exploitation of materials based on ancient Asian techniques.

Unfortunately some of these aesthetic propositions based on experimentations with ceramics materials and technologies remained without consequences for the ceramics work of Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, which ended with his death in 1905. They were not continued by his son Manuel Gustavo Bordalo Pinheiro (1867-1920), who took charge of the factory between 1906 and 1908.

However, Costa Motta Sobrinho (1877-1956) was to give effective modern continuity to Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro’s latest proposals. Like him, Costa Motta was to build a career in ceramics, not via the workshop but via an academic path provided by his training as a naturalist sculptor in Lisbon and Paris in the early 20th century.

Faience

Mark(s): “Raphael Bordallo Pin.” Caldas” and “FFCR

MRBP.CER.161